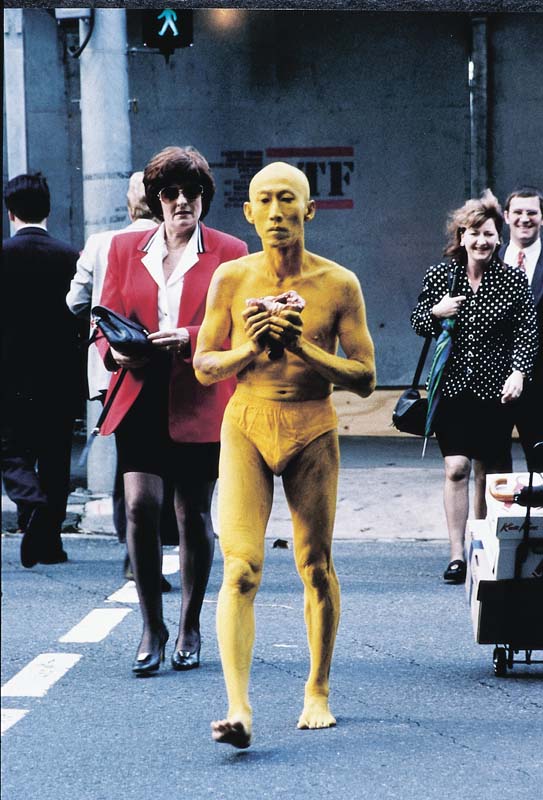

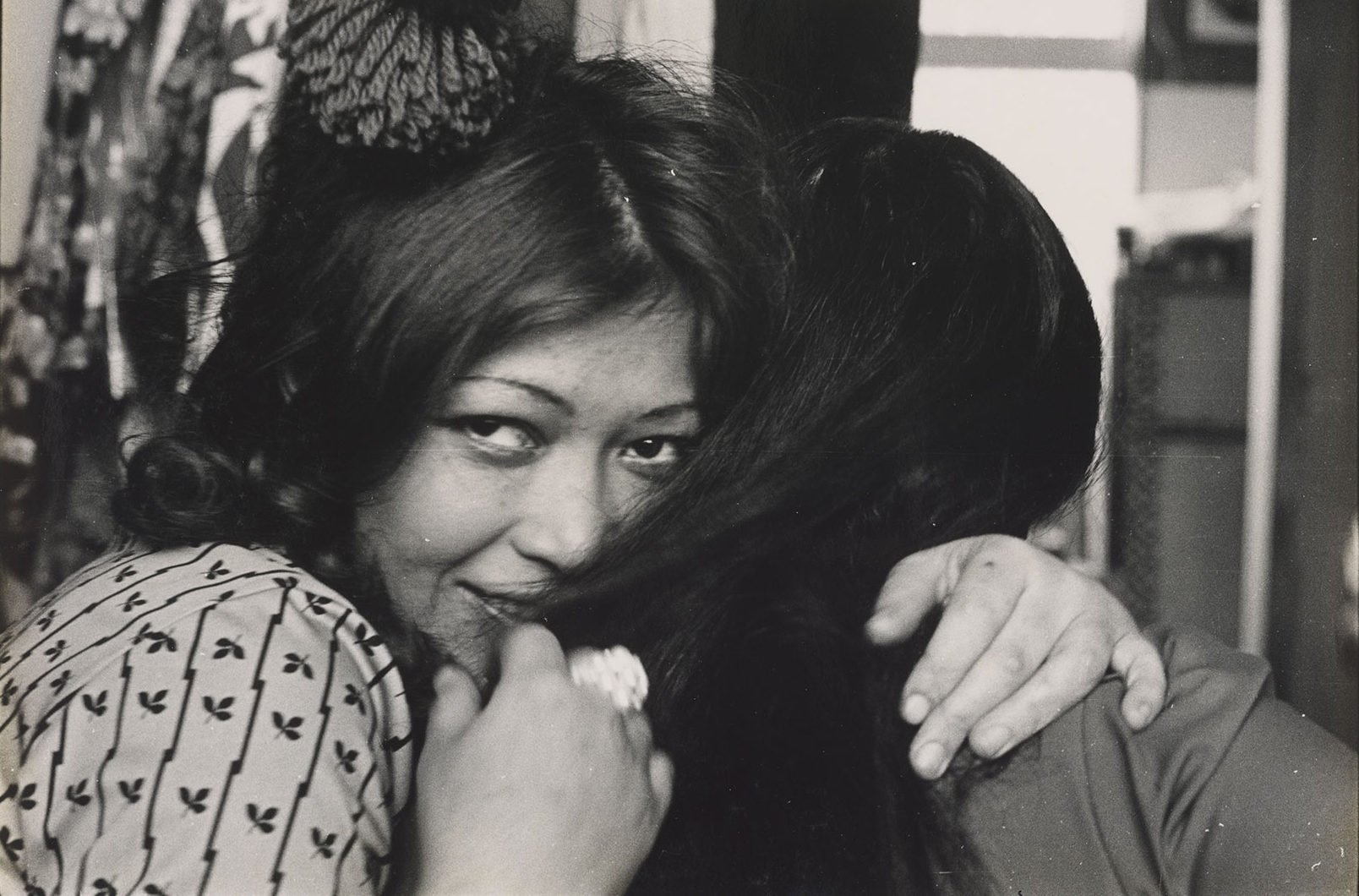

Koki Tanaka / Japan b.1975 / Abstracted / Family 2019 (installation view, ‘Aichi Triennale 2019: Taming Y/Our Passion’) / Image courtesy: Koki Tanaka

Koki Tanaka / Japan b.1975 / Abstracted / Family 2019 (installation view, ‘Aichi Triennale 2019: Taming Y/Our Passion’) / Image courtesy: Koki TanakaIn late July 2019, the Sapporo International Art Festival announced the theme and title of its 2020 edition in Japanese, English and — for the first time — the language of the Ainu people indigenous to northern Japan.1

A few days later, at the 2019 Aichi Triennale, artist Kōki Tanaka premiered works from his Abstracted / Family project, one of several projects by the artist produced in collaboration with Japanese people from diverse backgrounds, touching on the experience of haafu (half-Japanese), Zainichi (generations of ethnic Koreans) and Nikkeijin (migrants of Japanese ancestry).

In the same triennale, Hikaru Fujii debuted a video documenting a workshop produced with Vietnamese students living in Japan that re-enacted the wartime ‘Japanisation’ exercises conducted in occupied Taiwan. Meanwhile, the journal Bijitsu Techō (Art Notes) devoted a substantial proportion of its August issue to profiling the art of Okinawa, the country’s southernmost prefecture, whose shifting sovereignty has complicated its people’s relationship to Japanese nationality — a situation exacerbated by the continuing presence of major US military installations.2

These examples signal shifts in artistic consciousness away from conceptions of Japan as an ethnically homogenous society and toward an understanding that embraces diversity and complexity, challenging cultural erasures that even the established art system has maintained. Decolonisation has emerged as an important concern in contemporary Japanese art, thanks to the efforts of engaged artists, activists and grassroots organisation, as well as forward-thinking museum professionals’ engagement with international discourses. Although the process is in its early phase, decolonisation promises to further enrich one of Asia’s most well-established contemporary art infrastructures.

Two of these developments were overshadowed by global and local events: Sapporo was forced to cancel its 2020 edition due to the COVID-19 pandemic, while opportunities for nuanced discussion of the content of the 2019 Aichi Triennale were severely curtailed by threats of violence directed at a single sculpture. The withdrawal of the work, which raised the issue of enforced sexual slavery in Japan’s wartime past, sparked a debate on censorship in the arts. Despite these obstacles, both gestures appear to have enduring influence — the institution of Ainu consultation on an ongoing basis in the case of Sapporo; and direct engagement by Tanaka, Fujii and others with artist activism around the Aichi Triennale, as an extension of the content of their work.3

Ethnic minorities within Japan include the indigenous Ainu and Ryūkyūan (or Okinawan) peoples; successive generations of migrants from nearby countries, such as China, Korea, Taiwan and the Philippines; and newer populations from further afield. This diversity owes much to Japan’s imperial past. The Ainu homelands of Hokkaido, northern Honshu, the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin, and the independent Ryūkyū Kingdom (of the Pacific archipelago that takes in Amami-Oshima, Okinawa and the Sakishima Islands), were formally annexed early in the Meiji restoration after several centuries of feudal incursion. This preceded imperial expansion into Taiwan, Korea, Manchuria and beyond, with attendant policies of cultural assimilation and forced labour migration. These indigenous and foreign communities are joined by people with Japanese heritage, such as the overseas-born Japanese known as Nikkeijin and descendants of the untouchable Burakumin undercaste of the pre-modern feudal order, who continue to face systemic ostracism and discrimination. Collectively, they make up around two per cent of Japan’s total population; the real proportion is likely to be far greater.4 Until recently, these figures have done little to challenge the notion of Japan as an ethnically homogenous society, which operates both externally and internally.5

According to the prevailing theory, even the Yamato ethnicity that constitutes the majority of Japan’s population is itself complicated by an ancient admixture of Jōmon ancestors, who settled on the archipelago from South-East Asia in the Paleolithic era, with Yayoi arrivals from the Korean Peninsula in the first millennium BCE. Regional differences in dialect, cuisine and custom are widely recognised throughout the country. These understandings have not prevented theories of the uniqueness of the Japanese people — whose origins in late-nineteenth-century notions of ethnic purity crystallised into the body of thought known as Nihonjinron in the postwar era — from influencing public life. Arguably, these theories have also been perpetuated, albeit unwittingly, in the field of art.

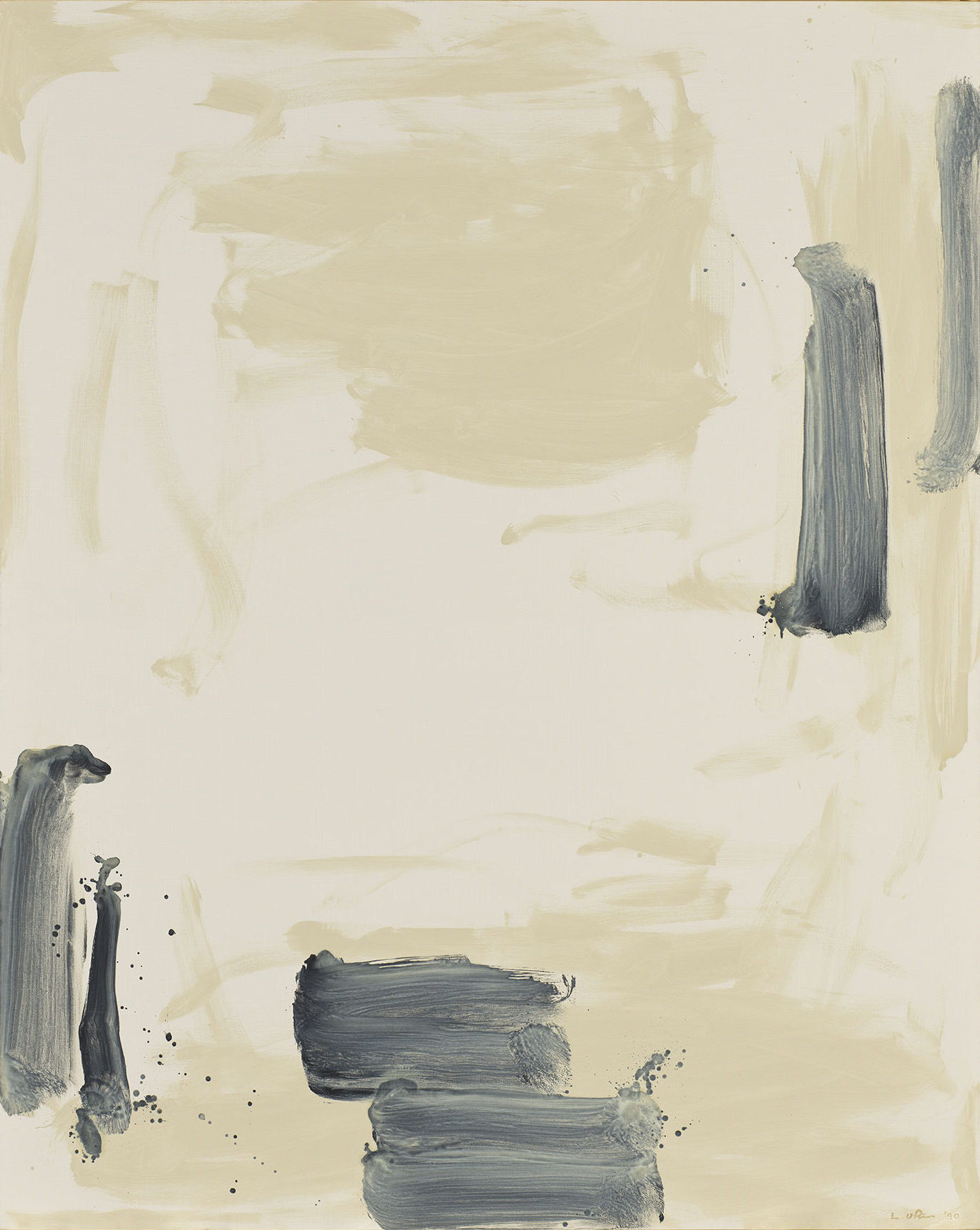

Lee Ufan / South Korea/Japan b.1936 / With Winds 1990 / Oil on canvas / 227.5 x 182cm / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 1998 with funds from Michael Sidney Myer through and with the assistance of the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Lee Ufan

Lee Ufan / South Korea/Japan b.1936 / With Winds 1990 / Oil on canvas / 227.5 x 182cm / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 1998 with funds from Michael Sidney Myer through and with the assistance of the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Lee Ufan Lee Ufan / South Korea/Japan b.1936 / Relatum 2002 / Iron plates, stones / 57 x 536 x 526cm (installed); four iron plates: 2 x 120 x 80cm (each); four stones: 57 x 57 x 58cm; 52 x 75 x 52cm; 44 x 69 x 53cm; 49 x 70 x 49cm / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 2002 with funds from The Myer Foundation, a project of the Sidney Myer Centenary Celebration 1899–1999, through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / ©Lee Ufan / Photograph: Natasha Harth

Lee Ufan / South Korea/Japan b.1936 / Relatum 2002 / Iron plates, stones / 57 x 536 x 526cm (installed); four iron plates: 2 x 120 x 80cm (each); four stones: 57 x 57 x 58cm; 52 x 75 x 52cm; 44 x 69 x 53cm; 49 x 70 x 49cm / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 2002 with funds from The Myer Foundation, a project of the Sidney Myer Centenary Celebration 1899–1999, through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / ©Lee Ufan / Photograph: Natasha HarthThere are, of course, notable exceptions to the idea that art in Japan is homogenous. Lee Ufan, who first moved to Japan from Korea in 1956, at the age of 20, played an outsized role in the development of Japanese contemporary art, most prominently as a theorist and spokesperson for the highly influential Mono-ha (School of Things) movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang relocated to Tsukuba in 1986, where he embarked on an attention-grabbing series of projects that earned him a place in the 1995 exhibition ‘Art in Japan Today’, which opened the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo. The command N collective, established in 1998, was particularly cosmopolitan, its number including Tokyo-based artists from a range of nationalities, such as Myeong-eun Shin from Korea, Lee Wen from Singapore, and English artist Peter Bellars. The broader composition of the Japanese art world has, however, been less diverse.6

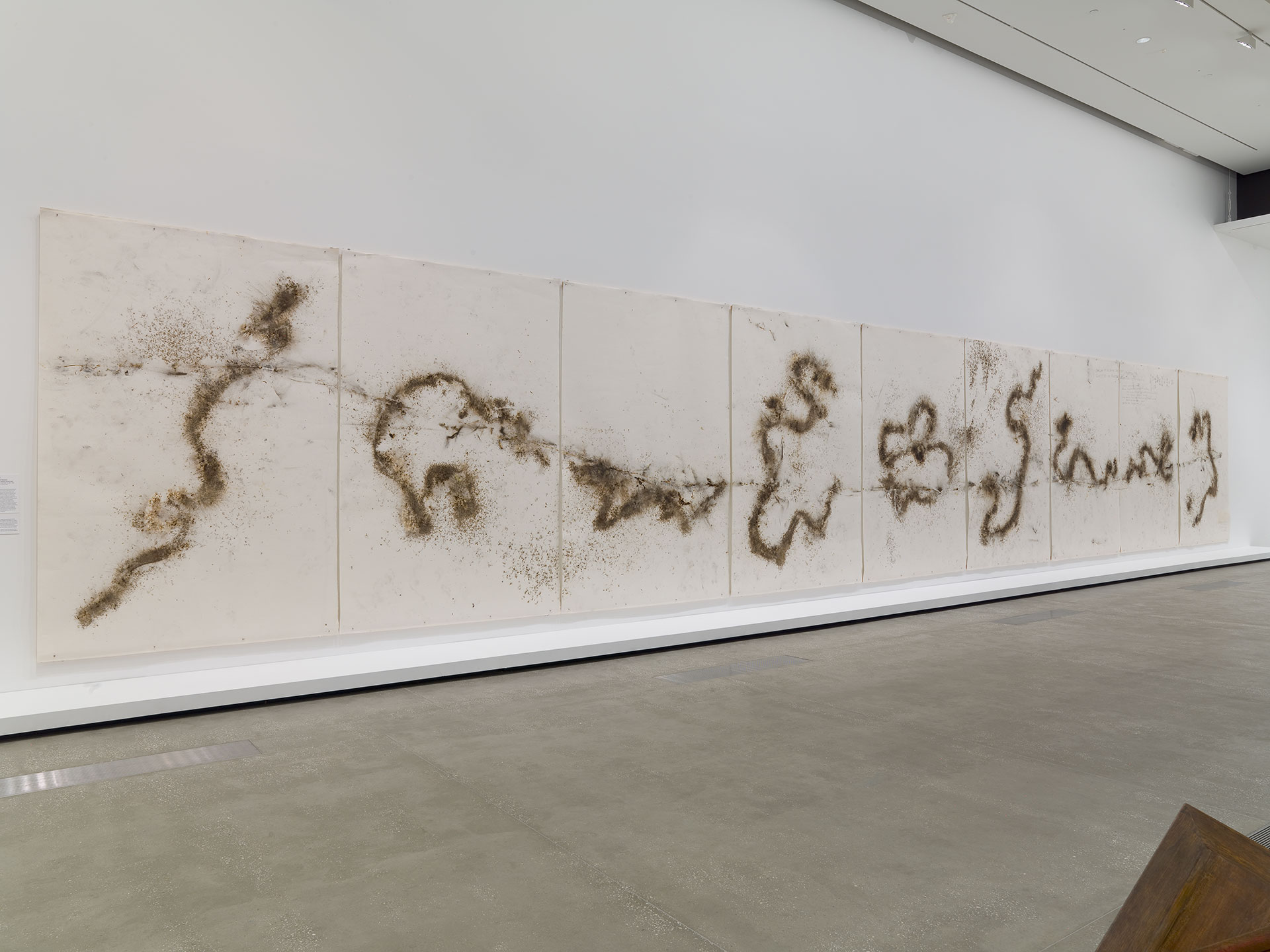

Cai Guo-Qiang / China b.1957 / Nine Dragon Wall (Drawing for Dragon or Rainbow Serpent: A Myth Glorified or Feared: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 28) 1996 / Spent gunpowder and Indian ink on Japanese paper / Nine sheets: 300 x 200cm (each); 300 x 1800cm (overall) / Purchased 1996 / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Cai Guo-Qiang / Photograph: Natasha Harth

Cai Guo-Qiang / China b.1957 / Nine Dragon Wall (Drawing for Dragon or Rainbow Serpent: A Myth Glorified or Feared: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 28) 1996 / Spent gunpowder and Indian ink on Japanese paper / Nine sheets: 300 x 200cm (each); 300 x 1800cm (overall) / Purchased 1996 / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Cai Guo-Qiang / Photograph: Natasha HarthIn recent decades, several Japanese organisations have worked to promote artistic dialogue with other parts of Asia. The commercial Tokyo Gallery was representing Korean artists as early as the 1970s and Chinese artists in the 1980s, while Fukuoka Art Museum established enduring ties from the time of its first Asian Art Show in 1979, which — with the founding of the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum in 1999 — evolved into the Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale. The Japan Foundation instituted a series of exhibitions, symposia and publications with the establishment of the ASEAN Culture Center in 1990, which expanded into the Japan Foundation Asia Center in 1995.7 The exhibition programs of such institutions as the Mori Art Museum and Yokohama Museum of Art also reflect a deep commitment to highlighting the work of artists of Japan’s neighbours, including those territories occupied during the period of Japanese colonial expansion. These acknowledgments of the sophistication and diversity of cultural contexts in Asia provide a strong foundation for the nascent explorations of Japan’s internal diversity.

The Sapporo International Art Festival’s use of the Ainu language comes at a time when the Ainu have received belated recognition by the Japanese government. In April 2019, Japan’s legislature, the National Diet, passed a bill acknowledging the Ainu as the indigenous people of Japan, obliging the state to support and protect Ainu cultural identity and ban discrimination. While the law offers no apology for mistreatment, and includes no stipulation for rights to land or resources, it does mark a departure from previous assimilation policies, beginning with the 1899 designation of Ainu people as ‘former aborigines’.8

Yamato Japanese artists are expressing interest in the history of northern Japan and the settler–colonial structures of that region. Sapporo-based multimedia artist Fuyuka Shindo has sought to deconstruct the pioneer rhetoric of the Meiji-era colonisation of Hokkaido, drawing parallels between the intensive development of the territory and the American notion of ‘manifest destiny’, whereby the expansion of dominion is divinely ordained.9 Photographer Keiji Tsuyuguchi’s series ‘Place names’, begun in 1999, documents sites throughout Hokkaido, presenting the current Japanese name of each alongside a phonetic approximation of its original Ainu name, as well as an explanation of its literal meaning.10 High-profile artist Yoshitomo Nara, best known for his cartoonish child and animal figures that mix manga cuteness with punk rebellion, has produced photographic works documenting Ainu homelands in the former Japanese (now Russian) territories of Sakhalin and Kuril Islands.

In 2017, sound installation artist Yuko Mohri produced Breath or Echo, inspired by the environmental sculpture Four Winds 1986 by Ainu modernist artist Bikky Sunazawa. Breath or Echo incorporates found materials from the former Yūbari coal mine in Hokkaido, and a poem composed by Sunazawa complements the sculpture. A youthful participant in Tokyo’s fertile avant-garde scene of the 1950s and 1960s before returning to Hokkaido, Sunazawa imbued Ainu woodcraft and spirituality with personal poetic expression on an ambitious scale. He is one of the few Ainu artists regarded as ‘contemporary’ in the commonly accepted sense of an inheritor of modernist styles and preoccupations. Ainu visual artists are primarily regarded as exemplars of folk traditions, valued more for preserving culture (and, to some degree, playing a role in the tourism industry) than for their contribution to the broader artistic dialogue. On the other hand, Ainu creators who are considered contemporary tend to operate in spheres conventionally beyond the remit of museums and galleries, such as the reggae music of the celebrated Oki Ainu Dub Band, led by Sunazawa’s son, Oki Kanō.

Nonetheless, some artists of Ainu heritage have recently been embraced by the contemporary scene outside Japan. In 2019, the work of illustrator and manga artist Sayo Ogasawara, best known for educational Ainu-language digital books and playing cards, featured in the National Gallery of Canada’s ambitious survey of international indigenous art, ‘Àbadakone’ (‘Continuous Fire’). Mayunkiki, who was Ainu Cultural Coordinator for the 2020 Sapporo International Art Festival before it fell victim to the pandemic, participated in the 2020 Biennale of Sydney with a photo narrative detailing her study of sinuye — the suppressed tattooing tradition of Ainu women. (Mayunkiki considers herself primarily as a singer, and through her work with Marewrew — a vocal group affiliated with the Oki Ainu Dub Band — is dedicated to preserving the a cappella singing style upopo.) Both Ogasawara and Mayunkiki belong to a generation whose parents underwent degrees of cultural assimilation in the face of discrimination, such that their work is as much a retrieval of personal identity as it is an expression of it. Despite some international recognition, their status as contemporary artists in Japan remains marginal.

Artists from Okinawa have arguably attained greater visibility in mainstream exhibitions of contemporary art in Japan over the past two decades. The island has held a unique place in the consciousness of Japanese progressives since the late 1960s, when student activists and the newly formed citizens’ movement turned their attention to the islands’ pending ‘reversion’ to Japanese sovereignty, following the long postwar occupation by American forces.11 Photographers associated with the New Left, among them Shōmei Tōmatsu and Takuma Nakahira visited Okinawa at a time when travel to the Ryukyu Islands still required a passport, to document tensions between locals and the US military. Tōmatsu would eventually relocate to the island, where he worked with emerging local photographers, such as Kenshichi Heshiki and Mao Ishikawa, who were sharpening their own perspectives on their homeland. The development of modern painting in postwar Okinawa by the likes of Hideo Kobashigawa, Masayoshi Adaniya and the Women’s Art Movement combined with the new photography to provide a bracing depiction of place altogether removed from the colourful, exotic manifestations of the Japanese gaze. Nevertheless, the work of these artists went relatively unseen outside Okinawa until the early 2000s.

In 2004, Mao Ishikawa’s powerful depictions of life on the margins of US military bases, captured over 30 years, were featured in a group exhibition at the Yokohama Museum of Art and sparked renewed interest in her work.12 Around this time, Yuken Teruya, who trained in Tokyo before moving to the United States to pursue further education, began attracting attention in New York for his intricate miniature tree sculptures constructed from store-branded paper shopping bags and other detritus.

In 2007, Okinawa became the last prefecture in Japan to receive its own art museum, consolidating activity that had hitherto taken place at the level of artist-run organisations. The Okinawa Prefectural Museum and Art Museum then produced a major survey with Tokyo’s National Museum of Modern Art, to which the exhibition toured, encompassing a range of both Japanese and Okinawan representations of the territory.13 Among a list of over 30 artists, the broad sweep of ‘Okinawa Prismed: 1872–2008’ included installation artist Kiyoko Sakata and video-maker Chikako Yamashiro, representing a new generation of Okinawan artists. They and their peers — photographer Ryuichi Ishikawa, video artist Futoshi Miyagi, sound artist Syo Yoshihama, to name a few — and the writers, performers and image-makers who make up the loose collective Las Barcas, have significantly affected the contemporary art of Japan, bringing queer, feminist, anti-nationalist and egalitarian sensibilities to bear on conditions in Okinawa.

Artists from other minority groups, such as the Zainichi and Burakumin, remain far less visible. To avoid discrimination, members of these groups feel pressure to conceal their heritage. For this reason, few figures within the Burakumin community have attained the level of prominence in the arts as the writer Kenji Nakagami, whose tough, uncompromising novels confronted the late twentieth-century literary world with life in the Buraku ghetto. While Zainichi perspectives have figured in Kōki Tanaka’s work, as well as that of Tadasu Takamine (whose partner is of Korean ethnicity), such representations leave open a question of agency when they are remain framed by artists from outside the Zainichi community, no matter how well intentioned.14

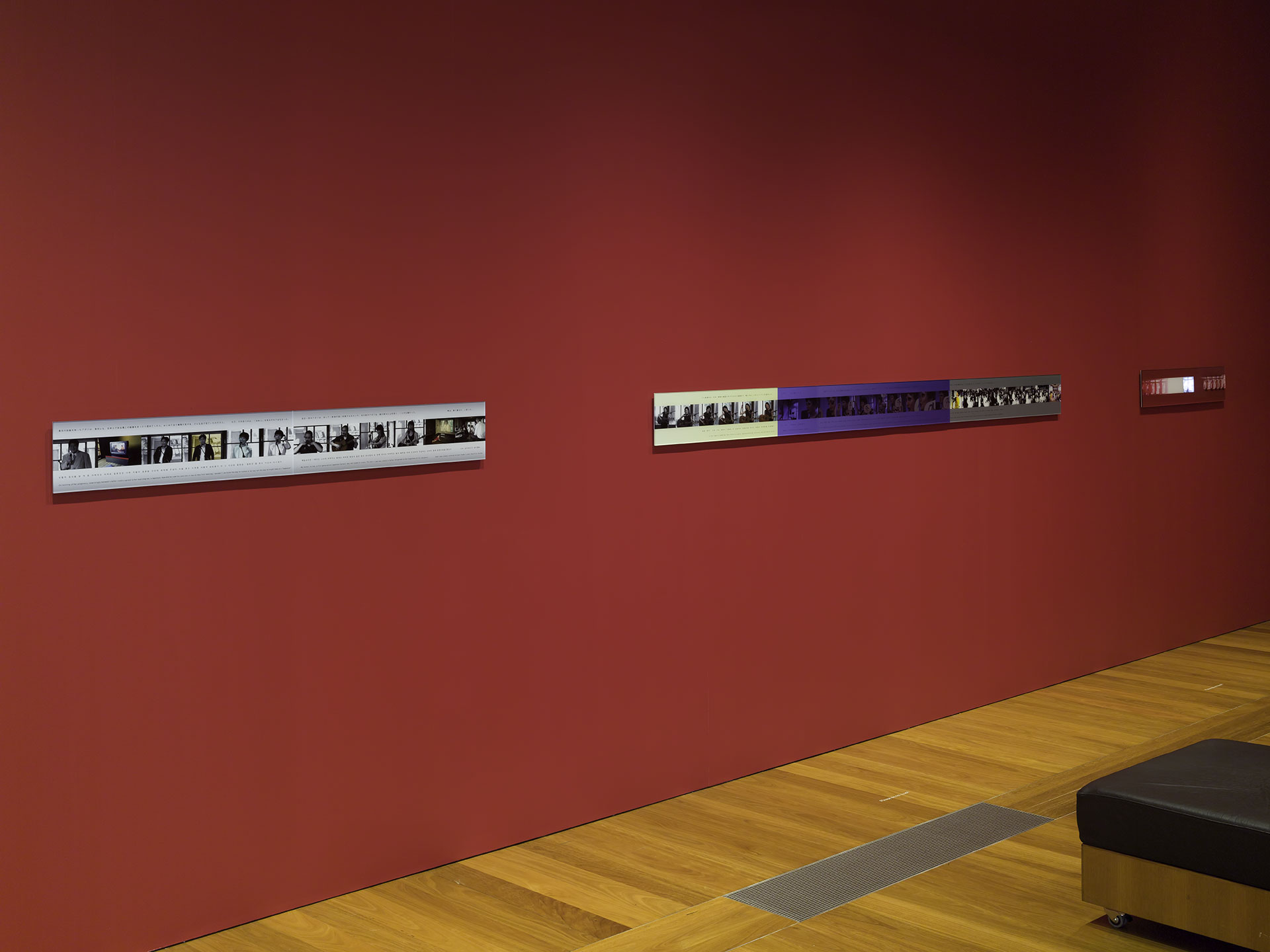

Tadasu Takamine / Japan b.1968 / Baby Insa-dong 2004, printed 2014 / Chromogenic prints mounted on acrylic, single-channel video [provided as DV and mp4 files]: 2:45 minutes, colour, sound, 7" LCD monitor / 15 panels: 20 x 95cm; 17 panels: 20 x 76cm; five panels: 20 x 93cm; installed dimensions variable / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 2014 with funds from Michael Sidney Myer through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection : Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane

Tadasu Takamine / Japan b.1968 / Baby Insa-dong 2004, printed 2014 / Chromogenic prints mounted on acrylic, single-channel video [provided as DV and mp4 files]: 2:45 minutes, colour, sound, 7" LCD monitor / 15 panels: 20 x 95cm; 17 panels: 20 x 76cm; five panels: 20 x 93cm; installed dimensions variable / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 2014 with funds from Michael Sidney Myer through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection : Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, BrisbaneNegotiation of identity is, of course, a problematic responsibility with which to burden an individual; embrace of identity at the level of artistic practice tends to vary between generations. Kwak Duck-Jun, best known for his conceptual and multimedia provocations of the 1970s, embodies the ambiguous legal status of Japan’s Zainichi Koreans: born in Kyoto in 1937 to Korean parents, his Japanese birthright was unilaterally stripped in 1952 when the Treaty of San Francisco came into effect and Japan relinquished its claim to the Korean Peninsula.15 Yet Kwak has resisted questions of identity, preferring instead to focus discussions on the substance of his work.16 On the other hand, third-generation artist Kim Insook has collaborated extensively with communities like those in which she was raised, teasing out the issues facing Zainichi Koreans in her photographic and video work SAIESEO: Between two Koreas and Japan 2008–. Her peer Soni Kum has touched on the sensitive issue of ‘ex-returnees’ – defectors from a North Korean-sponsored repatriation program – presenting their stories alongside staged solo performances in the multi-media work Morning Dew 2020. Kum has nevertheless spoken about her wariness as being seen as a spokesperson for the entire Zainichi community.

Mao Ishikawa / Japan b.1953 / A Port Town Elegy 1983–86 / Gelatin silver photograph on paper / 17.4 x 21.9cm / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 2018 with funds from Michael Sidney Myer through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Mao Ishikawa

Mao Ishikawa / Japan b.1953 / A Port Town Elegy 1983–86 / Gelatin silver photograph on paper / 17.4 x 21.9cm / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 2018 with funds from Michael Sidney Myer through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Mao Ishikawa Mao Ishikawa / Japan b.1953 / Red Flower: The Women of Okinawa 1975–77 / Gelatin silver photograph on paper / 23.1 x 15.4cm / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 2018 with funds from Michael Sidney Myer through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Mao Ishikawa

Mao Ishikawa / Japan b.1953 / Red Flower: The Women of Okinawa 1975–77 / Gelatin silver photograph on paper / 23.1 x 15.4cm / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 2018 with funds from Michael Sidney Myer through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Mao IshikawaThe shift towards collaborative practices in contemporary art may have opened a space for the expression of more marginal perspectives, where responsibility for representing a community is shared. This is the point at which Kim Insook and Soni Kum’s practice overlaps with that of inclusive artists like Tanaka and Fujii. Mao Ishikawa, who is explicit in rejecting Yamato Japanese identity, has produced arguably the most wide-ranging body of work in this vein, the long-running photographic series ‘Here’s what the Japanese flag means to me’.17 Since 1993, she has produced an enormous number of images of subjects requested to pose in ways that express the emotions evoked for them by Japan’s national flag, the hinomaru. Ishikawa’s subjects are a cross-section of Japanese and Okinawan society, from all parts of the political and ethnic spectrum, including Ainu, Buraku, Zainichi, indigenous Taiwanese and, significantly, people from parts of the Ryūkyū archipelago who face discrimination by mainland Okinawans. In this series, Ishikawa seeks solidarity among marginal groups, articulating passionate protest toward hegemony, while reflexively acknowledging the hegemony implicit in her own position.

Such efforts have benefited from a burgeoning acceptance of socially engaged art in Japan since the anti-nuclear movement briefly revived public protest in the wake of the Fukushima disaster of 2011. With notable precursors (and mentors) in the likes of Makoto Aida and Yukinori Yanagi, Yamato Japanese artists as diverse as printmaker Sachiko Kazama, video artist Meiro Koizumi, photographers Takashi Arai and Shitamachi Motoyuki, and mischievous collective Chim-Pom have been able to pose raise sensitive issues with a confidence that would not have been possible a decade earlier. However, as the controversy around the 2019 Aichi Triennale showed, this acceptance is not yet broadly embraced by society. The risk of artistic works causing outrage by posing uncomfortable questions is such that censorship, including self-censorship, is a definite prospect in Japanese exhibition culture; it is difficult for Ishikawa, for example, to exhibit the corpus of her work in mainland Japan without interference, despite her belated recognition.18

After decades of historical revisionism, which arose after the death of Emperor Hirohito in 1989, the task remains for artists and institutions to negotiate the reaction that inevitably ensues when the legacies of imperialism are critically examined. Furthermore, despite recent legislation aimed at curbing hate speech, discrimination still impedes expressions of identity and is not yet criminalised beyond certain municipalities. These society-wide problems extend far beyond the purview of art, but as the activism around Aichi reveals, both artists and institutions have a role to play in addressing them.

How the term ‘contemporary art’ and, more broadly, ‘Japanese contemporary art’ might be understood is still open for discussion. To this end, Kōki Tanaka has proposed a simple semantic shift, from the idea of ‘Japanese art’ to a more inclusive ‘art in Japan’, which detaches art from a term loaded with associations of homogenous ethnicity and instead locates it within a specific place.19 Given the welcome recognition of Chinese-born, Japanese-raised performance and installation artist Ishu Han, whose work where are you now 2020 and poetic ruminations on the experience of migrationwon him the prestigious Nissan Art Award in 2020. Tanaka’s proposed realignment is not only possible, but thoroughly rewarding.

The challenge for institutions and researchers into art in Japan is to expand these accommodations to the category of contemporary art itself by asking if the contemporary is simply a genre of production that requires recognisable codes, styles and modes of presentation for inclusion, and if there are other ways that art might reflect the present. Under which terms might a more inclusive definition of contemporary art be realised? As younger members of historically marginalised communities in Japan look to their elders and revive vanishing languages, techniques and knowledges that might contribute to possible futures — it is crucial for art to be flexible enough to include not only different identities, but also different ways of being contemporary.