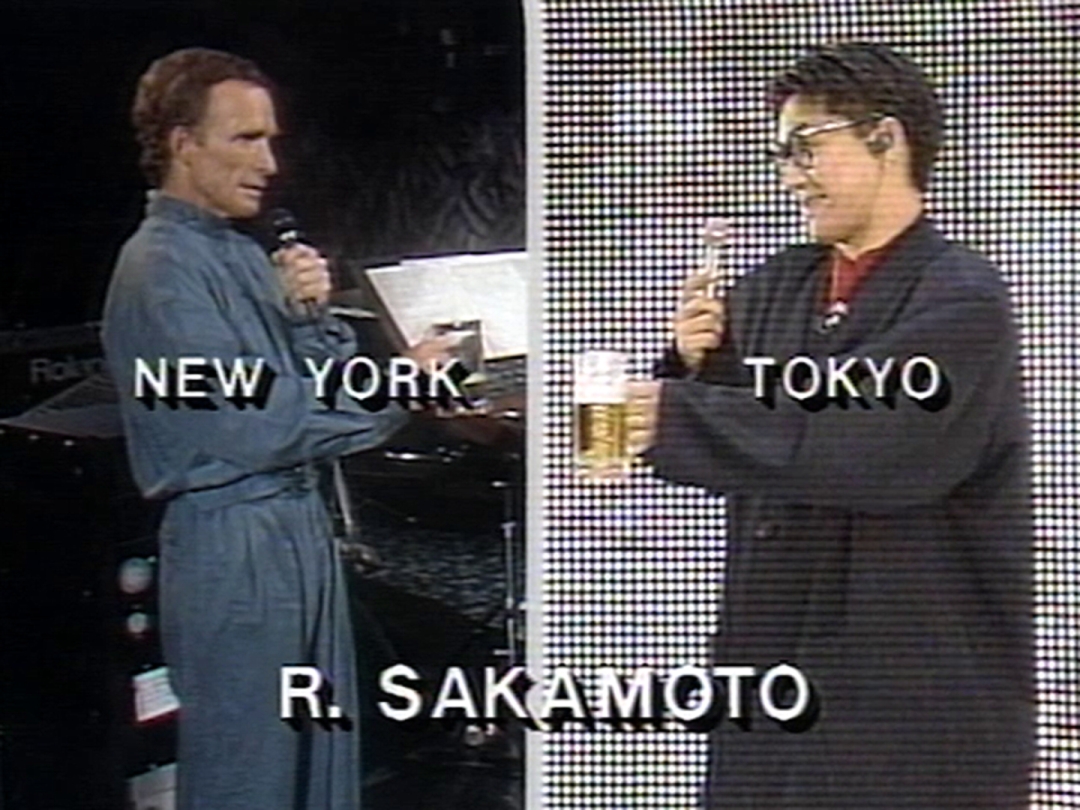

Nam June Paik / Bye Bye Kipling (still) 1986 / Courtesy: Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York / © Nam June Paik Estate

Nam June Paik / Bye Bye Kipling (still) 1986 / Courtesy: Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York / © Nam June Paik EstateIn 1986, Nam June Paik presented ‘Bye Bye Kipling’, a live event that connected Japan, Korea and the United States via satellite broadcasting technology, following the first satellite event in 1984, ‘Good Morning Mr. Orwell’, which connected the US and France. Using technology to evoke a consciousness of the new regional conceptions of the Pacific Basin, Pacific Rim and Pacific Ring, ‘Bye Bye Kipling’ was conceived as a response to a line by the late nineteenth-century English poet Rudyard Kipling: ‘East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet’. Taken from Kipling’s poem ‘The Ballad of East and West’, the line is followed by ‘But there is neither East nor West, Border, nor Breed, nor Birth / When two strong men stand face to face, though they come from the ends of the Earth!’, which gives some indication of the value system of a poet born in British India based on the equality of the human race. The first verse, however, is something of a platitude in the opposite sense, and so Paik named the event ‘Bye Bye Kipling’ in response.

Since the 1980s, when Paik presented this project, opportunities to see contemporary art from Asia have increased dramatically around the world. The 48th Venice Biennale in 1999 — when Harald Szeemann invited 19 Chinese artists to participate, and Cai Guo-Qiang won its International Prize — made a strong international impression regarding the rise of China.

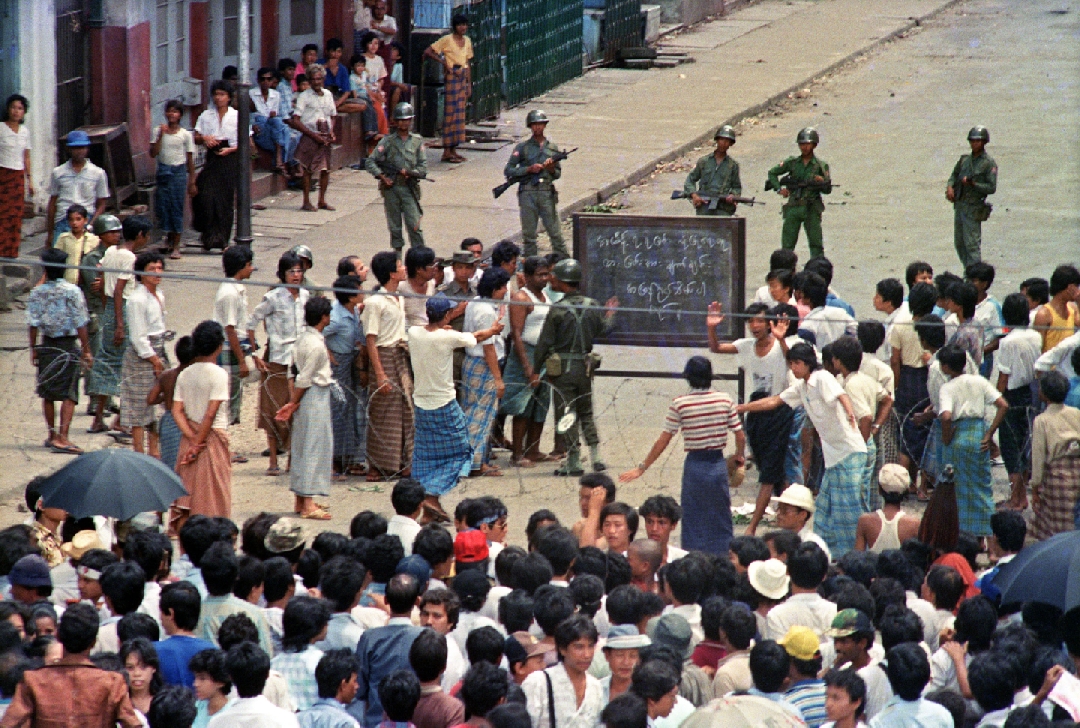

However, Asia accounts for more than half of the world’s population: it is a vast region where diverse nations, languages and religions coexist. Even if one were based in Asia, it would be nearly impossible to be cognisant of or discuss it as a whole. In fact, the attention directed towards Asia during this period was not so much in relation to the art itself, but rather, the remarkable economic growth of countries and regions such as Japan, China, India and South-East Asia. After World War Two, the Japanese economy, for example, continued to grow until the 1980s, and over-expanded during the latter half of the 1980s before collapsing in 1990. During this bubble economy, many ‘Japanese contemporary art exhibitions’ were held in Europe, North America and Oceania. This was partly due to interest in the culture of a country with a strong economic presence, including negative viewpoints represented by the ‘Japan bashing’ in the US, and also on account of the fact that exhibitions for overseas export had been made possible by funding from Japanese government agencies and corporations. This structure, in which economic and political interests are closely intertwined with cultural promotion, is broadly similar to that adopted in other Asian regions that have demonstrated a similar trend since the 1990s. China began to shift its policies towards reform and opening up after 1978: its GDP grew by more than 10 per cent during the late 1980s, making it the world’s second largest economy by 2011. India’s economic growth also accelerated after the introduction of economic reform measures in 1991, especially in service sectors such as the IT industry. China and India are among the so-called BRICS countries (along with Brazil, Russia and South Africa) that have experienced remarkable economic growth since the 2000s, while the rise of South-East Asia also attracted attention in the 2010s. The expansion of the wealthy classes due to economic growth in this region has also revitalised the art market. In tandem with this, the global art world also paid a great deal of attention to Asia, while Europe and the United States saw several concentrations of exhibitions of contemporary art from Asian countries and regions. Many countries in Asia underwent a period of political and social upheaval in the 1980s: in South Korea, democracy was declared in 1987 following the Seoul Spring democracy movement that had gained momentum in 1980 and the Gwangju Uprising; and in South-East Asia, Brunei gained independence from Britain in 1984, the Marcos dictatorship was overthrown by the EDSA Revolution in the Philippines in 1986, and the democracy movement in Myanmar known as the 8888 Uprising was suppressed by a military coup d’état in 1988 — the country continues to be painfully unstable, even today.

26 August 1988: Troops order a crowd in downtown Rangoon (Yangon) to disperse during the pro-democracy 8888 Uprising (8 August – 18 September 1988). The military killed thousands of civilians, including students and Buddhist monks. During the crisis, Aung San Suu Kyi emerged as a national icon. Photograph: TOMMASO VILLANI/AFP via Getty Images

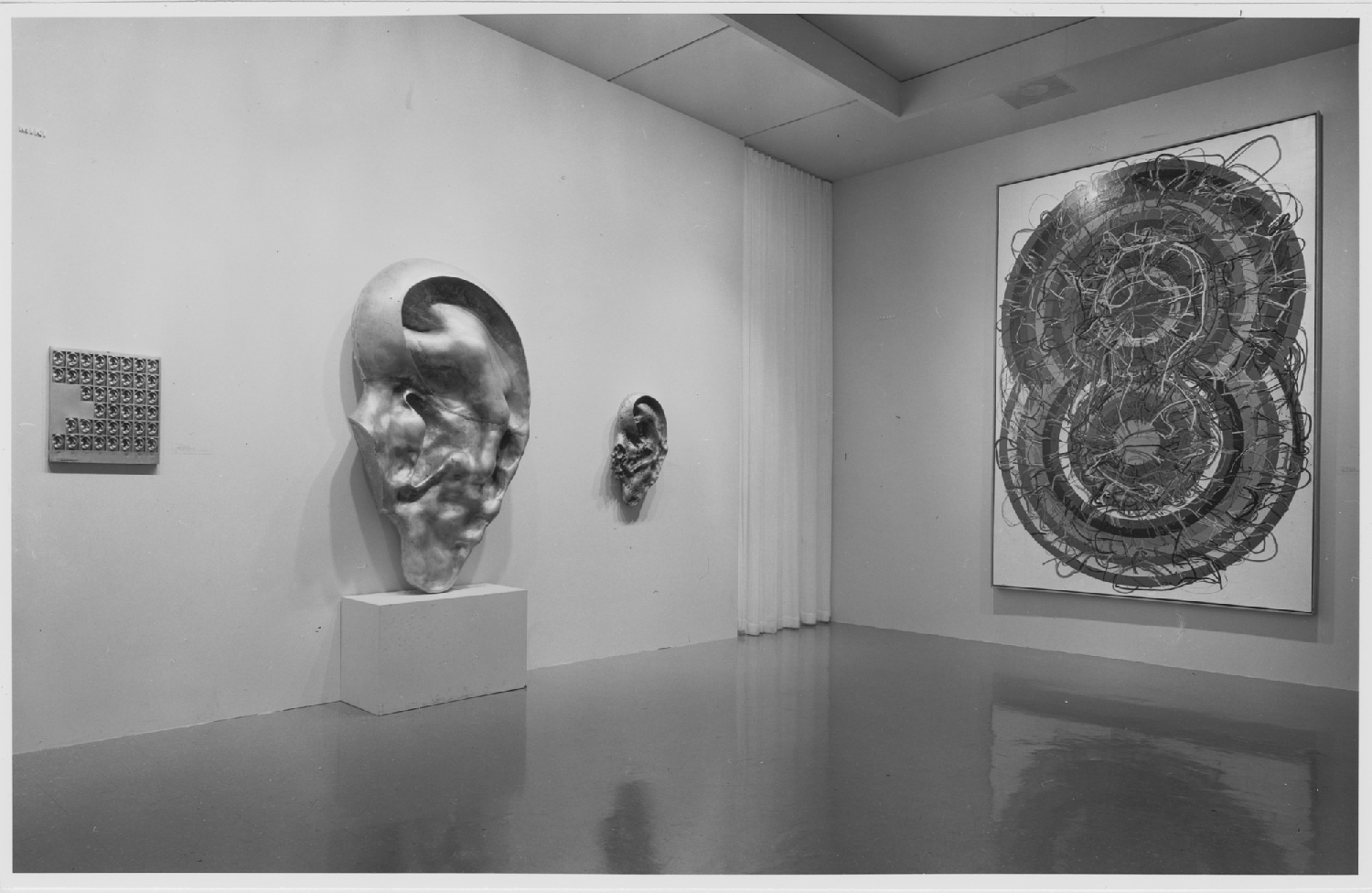

26 August 1988: Troops order a crowd in downtown Rangoon (Yangon) to disperse during the pro-democracy 8888 Uprising (8 August – 18 September 1988). The military killed thousands of civilians, including students and Buddhist monks. During the crisis, Aung San Suu Kyi emerged as a national icon. Photograph: TOMMASO VILLANI/AFP via Getty ImagesIn light of this background, the difficulty of communicating the pluralism and diversity of Asia to the outside world is obvious. It might be best to remember that there will always be a gap between the intentions and expectations of exhibition organisers and how such exhibitions are perceived outside Asia. At the same time, the ambiguity entailed by the practices of individual artists being inseparable from the political, economic and social conditions of the region, while not being necessarily interpreted only according to such regional identities, inevitably also comes into play when discussing art in the framework of countries and regions. To proceed with this essay on Asian art outside Asia, I would like to note here that, due to the limits of my own knowledge, the phrase ‘outside Asia’ refers mainly to the West. How did the West, the centre of art, see the art being produced on the periphery? I was prompted to think about this question more than a decade ago after encountering the following review of the exhibition ‘The New Japanese Painting and Sculpture’,1 organised by the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, which travelled to eight museums in the United States in 1965–67. As John Canaday wrote for the New York Times in 1966:

The Museum of Modern Art opened last week a dud of a show called ‘The New Japanese Painting and Sculpture.’ It could more appropriately have been called ‘The Old International Clichés Embalmed.’ The embalming job is perfectly beautiful, done with taste and immaculate craftsmanship, making the temporary exhibition galleries of the museum, until the show closes on December 26, the most handsomely decorated funeral parlor in the city. And the invisible corpse that dominates the place is that of the Goose that Laid the Golden Egg … The easy thing to do would be to dismiss the exhibition as pointless with a reminder that the Japanese have always been imitative, that as soon as the West has designed a good toaster the Japanese have always been right in there with an imitative product, and that in the arts they are now busy doing the same thing.2

The Guggenheim International Prize, established in 1956, eliminated its country-specific system and relaunched as the Guggenheim International Exhibition in 1967.3 Edward F Fry, who was involved in the selection process, also served as curator of this Japan exhibition. At the time, Fry noted that most of the ‘radically innovative’ sculpture of the day originated in America, primarily in New York and Los Angeles, and that other advanced centres were Tokyo, London, Dusseldorf, Milan, and Paris, thus validating Japan within an international context.4 In response, however, Canaday noted:

In spite of their determination to match the West on its own terms, however, Japanese artists today are haunted by ancestral ghosts. They suffer from the conflict between an ineradicably ingrained reverence for Japanese tradition — a kind of esthetic Shintoism — and a terror of being left behind in the international nihilism of contemporary art movements.5

Art critic Yoshiaki Tono, who had seen ‘The New Japanese Painting and Sculpture’ at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska, reported that ‘the majority of the American critics just about managed to see something “Japanese” in the artworks by replacing the fundamental awareness and problems that existed in contemporary art with the skillfulness of the finishing, craftsmanship, and “art-ness”’.6 Tono also points out that the radical phenomenon of ‘contemporary art’ is really ‘urban art’ — a ‘strange substitute for what might be called an urban republic’7 that connects the world’s major cities. Accordingly, bringing the perspectives of ‘tradition’ and ‘climate’ into this context creates a ludicrous discussion of how contemporary art goes in search of ‘tradition’.8

Leaving aside Canaday’s distaste for the avant-garde, it is still easy to imagine the divergence between the intentions of the exhibition organisers and participating artists and the consciousness of their audience. As mentioned above, while a considerable number of exhibitions of contemporary Japanese art were held in Europe, North America and Oceania from the late 1980s and through the early 1990s, this divergence did not seem to shift much. As long as we continue to place the West at the centre or forefront, art produced in non-Western countries will naturally be perceived through the lens of preconceptions relating to the idea of a ‘periphery’ or ‘delay’, or the otherness of ‘tradition’ and ‘climate’. Conversely, while it is possible that those showcasing their work are strategically representing a sense of their own otherness, it is undeniable that the periphery has been gazing intently at the centre and trying to get closer to it. Here lies the collective illusion of something universal that might be shared globally as ‘contemporary art’. On the other hand, however, it is inevitable that unique cultural traditions and the political and social environment of a particular time are projected onto the production of that art. Furthermore, as art historian Reiko Tomii points out in her book Radicalism in the Wilderness,9 personal ‘connections’ and ‘resonances’ observed in the absence of direct connections ought to be deciphered in detail in each individual case. Asia, in fact, is the sum total of all of these.

Curator and scholar Alexandra Munroe has explored this multilayered-ness and complex intertwining from several perspectives, including various postwar Japanese art movements and artistic media such as butoh dance and early video works, in the exhibition ‘Japanese Art after 1945: Scream against the Sky’, held in Yokohama, New York and San Francisco in 1994–95. The following review of this exhibition by Holland Cotter of the New York Times shows the interesting shift in consciousness since the 1960s:

In a sense, the show’s major achievement is to shatter cliches. Anyone who regards contemporary Japanese art as a watered-down version of Western modernism has a surprise in store. Many of the artists included here have been pioneers in styles — Conceptualism, performance art, body art — that America and Europe tend to claim as their own; and Japan’s adaptation of such movements as Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism is … done with a highly selective eye that gives their models new meanings … Tradition is flouted at one moment, revived at another. Western influence is alternately embraced and rejected. Extreme distortions of image and material are less often used to gain distance from a culture than to more thoroughly mine its core.10

This shift in consciousness may have been due in part to the major trends of the multicultural era that confronted the world following the collapse of the Cold War structure in 1989. It shed light on the development of Modernism not only in Asia, but also in other non-Western regions such as Eastern Europe, Latin America and Africa. Early precursors of this trend were already present in the 1980s: well-known examples include ‘‘Primitivism’ in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern’, held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, from 1984 to 1985, as ‘the first ever to juxtapose modern and tribal objects in the light of informed art history’,11 and ‘Magiciens de la Terre’, held at the Centre Pompidou in 1989.

The combination of these trends and economic development in Asia resulted in regional exhibitions of Asian contemporary art being held in Europe and the United States in the 1990s. It might be interesting to compare two iconic exhibitions: ‘Contemporary Art in Asia: Traditions/Tensions’,12 organised by the Asia Society in New York in 1996; and ‘Cities on the Move’, which toured Europe and Asia, starting at the Secession in Vienna in 1997. Both exhibitions were attempts to get the audience to imagine the clichés of ‘old Asia’, conjured by traditional culture, in relation to the ‘new Asia’ of modernisation and urbanisation. For the former, 27 artists from five countries (India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Korea and Thailand) were selected from the perspective of religious forms and ideas, gender issues, and colonial history and contemporary realities. In the latter, curators broke away from the idea of the nation-state and focused instead on conurbations in Asia, where modernity has become a daily reality while the conflict between it and tradition persists, thereby distancing themselves from the identity politics at the centre of debate at the time. In addition to contemporary art, ‘Cities on the Move’ also encompassed the fields of architecture and urban planning, expanding its perspective to include the concept of modernity. The number of featured artists, which started at about 80, expanded and changed over the years as the exhibition continued to tour, with a total of almost 300 artists participating over three years.

In the catalogue accompanying ‘Traditions/Tensions’, the exhibition’s curator, Apinan Poshyananda, described Asia’s pluralism in the following way:

Asia: Its dynamism is matched only by its diversity. Asia is serene and sickly, seductive and sadistic, desirable and destructive, tranquil and traumatic, democratic and despotic, oriental and disoriented, and much more.13

While devoting much space to outlining the difficulties of changing Western stereotypes and preconceptions of Asia, Poshyananda also tries to complicate the tired dichotomous structures of West and East, centre and periphery. In particular, he points out that in North America, Asia has long been represented by East Asia, such as China, Japan and Korea; and at a time when identity politics was the focus of attention, some Asian artists intentionally adopted traditional culture and Western stereotypes as their subject matter. Poshyananda also raises the question of how to reflect the fluidity of Asia against the backdrop of its rapid change. In the same catalogue, art critic Thomas McEvilley points out that, amid rapid changes in the global balance of political and economic power since the late 1980s, there have been more opportunities to experience non-Western art in Europe and the United States, but most of them have been curated by Caucasians and Westerners. McEvilley also highlights how the cultures of regions considered ‘primitive’ by the West in the nineteenth century were showcased in cabinets of curiosities through objects seized by Western explorers, then held in ethnographic and anthropological museums in the twentieth century, and it was not until the 1930s that they came to be displayed in art museums. For this reason, he argues that:

[‘Traditions/Tensions’] shows neither, on the one hand, control by or obeisance to the West nor, on the other hand, dread of the West in favor of an insistence on the purity of other traditions … For the first time, we have a show of contemporary Asian art that arises from Asia itself, yet with connections, both institutional and cultural, to the West. There is a confidence to this stance that might not have been possible even as recently as a decade ago.14

In response to this, art historian and curator Alice Yang (1961–97) argued that

this type of visual disharmony had the opposite effect from what the organizers intended. Aware that the specific cultural references in each work might not be apparent to first-time visitors, as the exhibition explained, the organizers hoped the works’ ‘visual language [would] be potent enough to transcend national and cultural boundaries’. The exhibition’s often awkward illustrations and juxtapositions, however, undermined this potential at a number of turns.15

Nonetheless, Yang concluded that the exhibition prompted a deep reflection on art.

On the other hand, the exhibition ‘Cities on the Move’, co-curated by Hou Hanru and Hans Ulrich Obrist, presented a showcase of unfamiliar Asian contemporary art and cities that underwent a gradual transformation from one venue to another, mainly in Europe and the US. It also attracted attention as a curatorial model that departed from the conventional travelling exhibition. In a sense, the exhibition was a projection of contemporary Asia in all its rapid transformations. Hou recalls that there was ‘a global network between Asian cities. This was interesting in terms of a new kind of internationalism. Although there were conflicts between modernity and tradition, modernism had already become commonplace in urban areas’.16 The speed, density, mutation, migration and ecology of the cities of the ‘new Asia’ were conveyed through an exhibition that I experienced during its Vienna iteration: brimming with dynamism and energy, it seamlessly combined architectural structures and artworks, and was vibrant enough to make one feel that there was something happening in Asia. In fact, East and South-East Asia during this period were in the throes of economic and political upheaval with the Asian currency crisis of 1997 and the return of Hong Kong to China that same year. Clearly, the idea of utopian optimism was at a low ebb. Despite speculation about uncertainty, however, the pace of change and growth in Asia was sustained. ‘Cities on the Move’ was not only practically the first opportunity for Western audiences to encounter this ‘new Asia’, it was also the first chance for many of the participating Asian artists and architects to get to meet their Asian colleagues of the time. Since then, they have expanded their activities globally, and many of them today are leaders and trendsetters in Asian contemporary art and architecture. It was around this time that ‘relational art’ took the art world by storm, and the ‘Traffic’ exhibition from which it originated was held in 1996 at the CAPC (Museum of Contemporary Art Bordeaux). The spirit of participatory art and self-organisation was on full display at ‘Cities on the Move’.

The multipolar and pluralistic development of global modernism was subsequently unraveled at exhibitions such as ‘Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s’ (Queens Museum of Art, 1999), ‘Century City’ (Tate Modern, 2001), ‘Global Feminisms’ (Brooklyn Museum, 2007) and ‘The World Goes Pop’ (Tate Modern, 2016). In addition, contemporary Asian artists have made remarkable appearances at international exhibitions established in various countries, creating many biennial stars, and it is no longer unusual for them to have solo exhibitions at major museums around the world. Of course, there have also been many ‘Asian contemporary art exhibitions’ or country-specific Asian exhibitions, held in Europe and the United States.

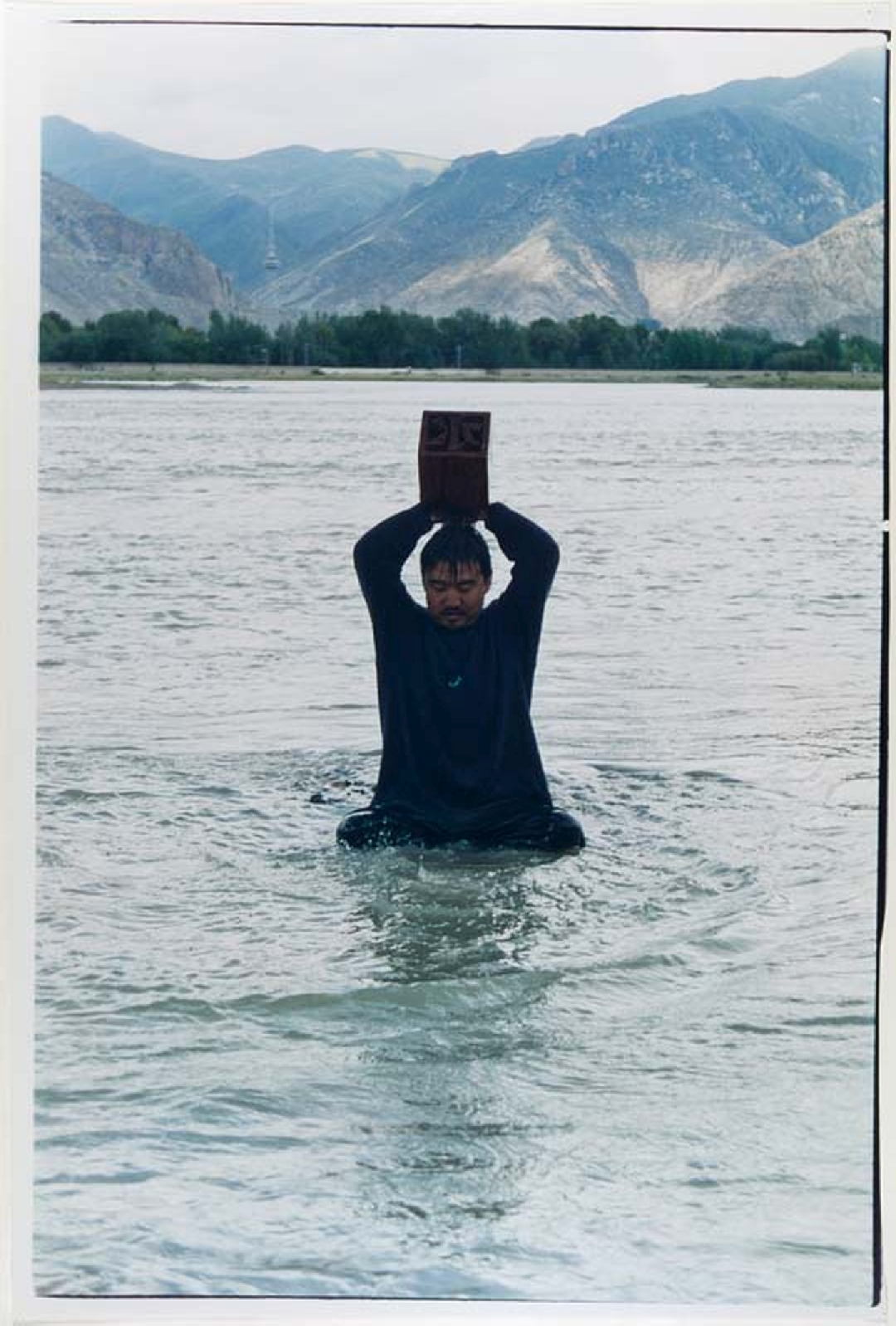

China was the first Asian country to attract attention starting in the 1990s. In 1998, ‘Inside Out: New Chinese Art’,17 which was shown at Japan Society, MoMA PS1, and then at SFMoMA, was the first major exhibition to showcase a new generation of Chinese artists from mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, as well as those who had immigrated to the West. In 2003, ‘Alors, la Chine?’ (‘Well Then, China?’) at the Centre Pompidou showcased 50 contemporary Chinese artists from China and other countries around the world. Funded by the Chinese Ministry of Culture, this was the largest Chinese exhibition ever held in France and the first Chinese exhibition at the Pompidou. Subsequent interest in India could be seen at the 2006 exhibition at the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, ‘Sub Contingent: The Indian Subcontinent in Contemporary Art’ (covering Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Myanmar and the Maldives), as well as ‘Indian Highway’ at the Serpentine Gallery in 2008–09. Then, the first Indian Pavilion appeared at the Venice Biennale in 2011. In terms of South-East Asia, the exhibition ‘36 Ideas from Asia: Contemporary South-East Asian Art’, organised by ASEAN and the Singapore Art Museum in 2002–03 and which toured Europe (MKM Museum Küppersmühle für Moderne Kunst, Duisburg, Schloss Museum Keszthely, Keszthely, Ungarn, Rupertinum, Salzburg), was an early example. Seng Yu Jin, an expert on the history of exhibitions, argued that ‘36 Ideas’ marked a beginning of a real attempt to forward new approaches and methods for curating and thinking about the region’s art and artists, departing from earlier notions and claims of Southeast Asian art as a fixed category’.18 The 2010s saw ‘No Country: Contemporary Art for South and Southeast Asia’ (2013) held as part of the Guggenheim Museum’s acquisitions program, while Europe hosted ‘The Roving Eye: Contemporary Art from Southeast Asia’ (2014–15) at ARTER, Istanbul; ‘Secret Archipelago’ (2015) at Palais de Tokyo, Paris; and ‘Open Sea: Artists from Singapore and Southeast Asia’ (2015) at the Musee d’art contemporain de Lyon. Slightly later, in 2020, the Asia Society established the Asia Society Triennale.

While it would be difficult to give an exhaustive account of all the reviews of these regional and country-specific exhibitions here, what they all share to some extent is a case of acute indigestion regarding the multilayered-ness and complexity of the exhibitions, even as a few individual artists are singled out for praise. In other words, they are a reminder that there are certain limitations to curating an exhibition that seeks to convey the totality of Asia within a limited space and time. The practices of individual artists already reflect extremely complex social and political shifts, and the contexts projected onto visual objects and images are intricately woven together to form the entirety of an exhibition. However, for most of non-Asian viewers, given the limited historical, social and cultural knowledge and experience of Asia as both a region and as single nation states, deciphering these contexts requires an enormous commitment. There is no denying that the introductory function of presenting Asia as a region has been meaningful. However, it is always an incomplete or aborted attempt for an exhibition to represent the diversity and pluralism of Asia and its countries, or to convey its complexity. Even in cases where the consciousness of Asia as periphery and belatedness was dispelled, a new obstacle presented itself: its diversity and pluralism. There is no single Asian or country-specific exhibition to be held, but rather, an infinite number of curatorial possibilities. In this sense, I cannot help but empathise with the following readings, for instance. For ‘Indian Highway’, Charles Darwent argues that ‘the result is that Indian Highway feels condescending, both to that Western audience and to the artists in the show. I’m sure there is a great deal of good art being made in India today, and equally sure that it is not to be seen here’.19 Regarding the Asia Society Triennale in 2020, Jason Farago writes that

bringing these artists and others together under one umbrella feels, at best, haphazard. This is a triennial in search of a reason for being — although that does not make it so different from hundreds of others … Between the shortcomings of our ‘global’ shows and the timidity of our ‘local’ ones lie a thousand possible encounters, where we can meet in ways that truly change us.20

Once we accept the impossibility described above, for what should Asia then strive? In terms of the development of modern and contemporary art in the Asian region, transregional historical research is being pursued not only in comparison with the West as the centre, but also with other non-Western regions outside Asia. There is also an emerging debate from the perspective of the Global South, which includes Asia and the Pacific, Latin America and Africa. It may take some time before this academic research and discussion can be projected onto the form of an exhibition aimed at a wider audience, and before this awareness of world art history can penetrate society at large, but this direction is ripe with potential.

Also evident is how the postcolonial debate of the 1990s has evolved into a discussion of the decolonisation of museums in the 2010s. At the museum level, former suzerain states are taking innovative steps by starting to reckon with the legacies of the colonial era. The Netherlands, for example, is considering the return of cultural heritage unjustly acquired in Asia, Africa and elsewhere since the seventeenth century. The artistic practices of indigenous peoples are also being increasingly evaluated. Amid these developments, it is also imperative to unravel the complex entanglements within the Asian region, rather than the relationship between West and East. In 2020, the Mori Art Museum and the Hyundai Tate Research Center: Transnational organised an online symposium entitled ‘From Alexandria to Tokyo: Art, Colonialism, and Entangled Histories’.21 A number of cases were presented in which individual artistic practices were intricately intertwined with the political and economic currents of the nation state in the context of Asia, or relations between Asia and the West. I believe that a cumulative understanding of these small individual narratives will promote a pluralistic understanding of Asia, both within and outside the region.

A still from filmmaker Meiro Koizumi’s Portrait of a Young Samurai 2009 was used to illustrate the Mori Art Museum and Hyundai Tate Research Center: Transnational’s 2020 online symposium ‘From Alexandria to Tokyo: Art, Colonialism, and Entangled Histories’ / Courtesy: The artist and Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam / © Meiro Koizumi

A still from filmmaker Meiro Koizumi’s Portrait of a Young Samurai 2009 was used to illustrate the Mori Art Museum and Hyundai Tate Research Center: Transnational’s 2020 online symposium ‘From Alexandria to Tokyo: Art, Colonialism, and Entangled Histories’ / Courtesy: The artist and Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam / © Meiro Koizumi Since the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, the issue of racism has once again surfaced, especially in the United States. Hate crimes against Asian immigrants have also increased two to three times compared to last year. In this essay, I was not able to touch on Asian-descent artists based outside Asia, but there is a need for a deeper understanding of their contributions within this region. In the global contemporary art scene today, it should also be noted that there are certain overlaps between the generation that migrated from Asia to Europe, America and Oceania at various times, and that of their descendants — the generation that has been practising since the 1960s and 1970s, that has been active on the world stage since it expanded in the 1990s, and the new generation in the post-globalisation, post-Internet era.

What we call ‘the world’ is, in fact, an accumulation of numerous localities. Both the West, which has long played a central role, and the space we call Asia, contain their respective localities. In that sense, we live in a time that impels us to prioritise the deepening of mutual understanding among the many localities within Asia, instead of seeking to evaluate the West. In terms of regionalism, it would also make sense to expand the scope of our awareness to the Asia Pacific region, including Oceania, or even further, to the idea of the Pacific Rim from the 1980s. As we recover from the pandemic crisis, while various social divisions persist, if we want to connect localities in Asia to one another, we need to go beyond East and West, border, breed, and birth, as Kipling’s ballad has it, and arrive at a keen appreciation of the importance of the simple and earnest work of accumulating all of these individuals, these face-to-face encounters. It is a tremendous challenge, and I wonder if the misunderstandings contained in Kipling’s platitudes might someday be dispelled.