Invasion Day rally, Melbourne 2019 / Photograph: Matt Hrkac/Flickr

Invasion Day rally, Melbourne 2019 / Photograph: Matt Hrkac/FlickrIt has become customary at official functions in Australia to be welcomed to Country by a Traditional Owner, or at least to have an Acknowledgment of Country delivered by the host of the event. A politician, community leader, CEO or conference organiser will stand at a microphone and acknowledge Traditional Owners, pay respects to Elders and other First Nation peoples at the gathering and recognise the sovereignty of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders over the lands and waters on which the meeting occurs. There is a distinction: ‘Welcomes’ can only be issued by those identified as having sovereignty over that Country; ‘Acknowledgments’ are provided by visitors to those lands. And although welcoming people to Country is an age-old practice on this continent, it is only in living memory that acknowledgments have become an important social and political function of living and working on Aboriginal land.

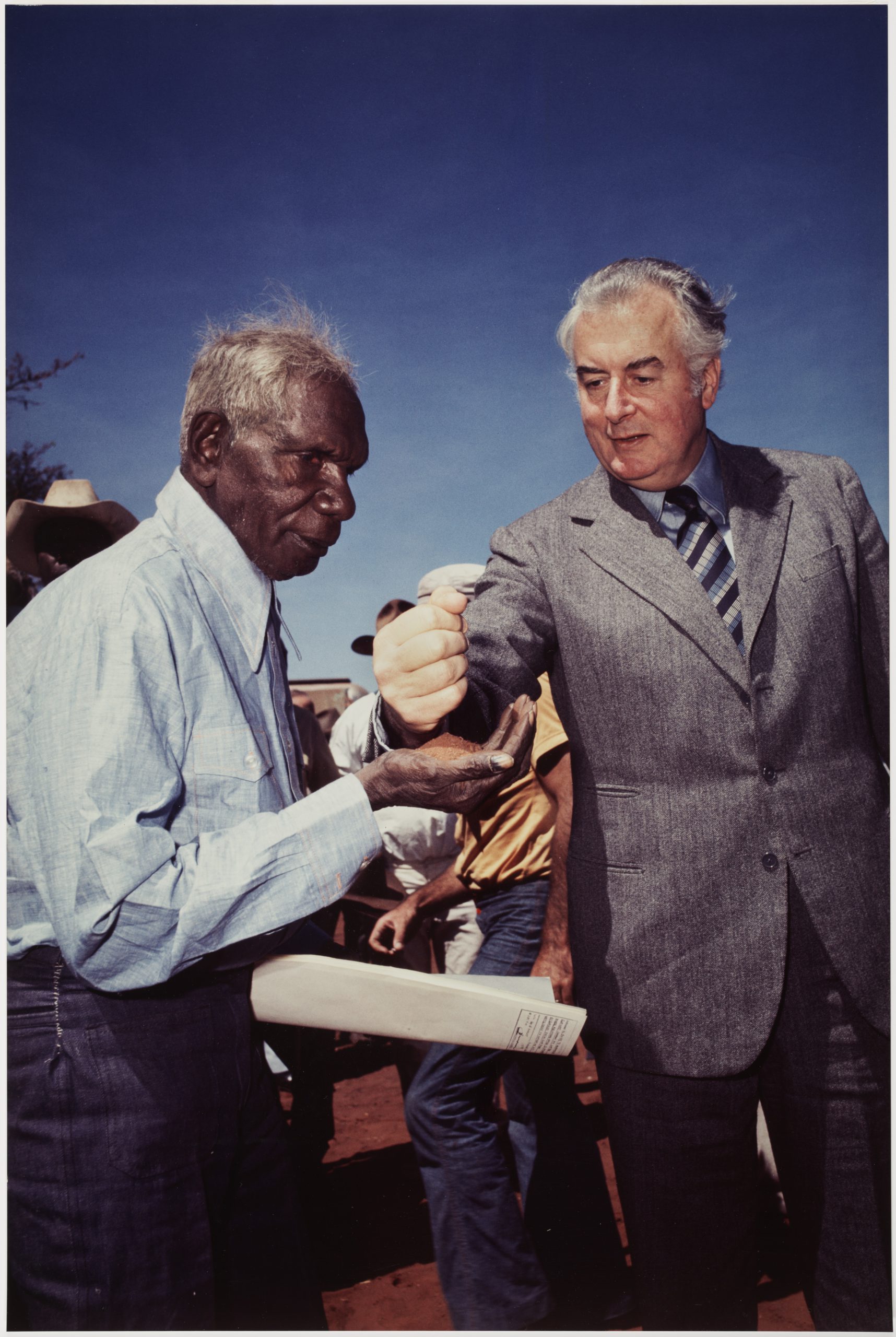

The phrase ‘Always was, Always will be Aboriginal Land’ is attributed to Uncle Jim Bates’s explanation, in the 1980s, of his unbroken connection to his Barkandji Country. Like the Aboriginal flag, first designed by Harold Thomas in 1971, this phrase has become ubiquitous and synonymous with land rights, self-determination and sovereignty. We have seen iconic images and words take on important roles in the changing Australian landscape, and these have created symbols, encapsulating the struggle in words, phrases, movements and images that affect the hearts and minds of those who encounter them. You only have to look at the life and work of Aboriginal artist Albert Namitjira to understand the profound effect he had in expressing love of Country within the political environment in which he painted. Similarly, the work of poet, activist and public speaker Oodgeroo Noonuccal, who gave shape to the ambitions that led to the 1967 Referendum in her 1962 poem ‘Aboriginal Charter of Rights’, is inspiring. And the 1975 photograph by Mervyn Bishop of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pouring red sand into the hand of Vincent Lingiari helped capture a moment that would go on to inspire songs and documentaries, and further the understanding of the land rights movement.

Mervyn Bishop / Australia b.1945 / Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pours soil into the hands of traditional land owner Vincent Lingiari, Northern Territory 1975, printed 1984 / Type R photograph / 76 x 50.7cm / Purchased 1994 / Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney / © Mervyn Bishop / Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet / Photograph: AGNSW

Mervyn Bishop / Australia b.1945 / Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pours soil into the hands of traditional land owner Vincent Lingiari, Northern Territory 1975, printed 1984 / Type R photograph / 76 x 50.7cm / Purchased 1994 / Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney / © Mervyn Bishop / Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet / Photograph: AGNSWArtists have been at the forefront of creating and documenting social and political change throughout the history of this nation. This history reaches back to the cultural practices of chronicling trade with our northern neighbours, from Makassan prahu (ships) painted on rock surfaces on Groote Eylandt, the arrival of tall ships, the petitions of Yorta Yorta Elder William Cooper, the bombings by Japanese aircraft during World War Two and the Yirrkala Bark Petitions, through to the The Uluru Statement from the Heart of 2017. The work of artists, their poetry and images reflects the aspirations of First Nation people, the social and policy shifts of decision-makers, and the growing dialogue between First Nation people and the more recently arrived.

Over the past 30 years, Australians have marked two significant anniversaries that go to the heart of our national storytelling: in 1988, it was the 200th anniversary of the arrival of the First Fleet and the beginning of the colonial project; while 2020 marked the 250th anniversary of Lieutenant James Cook arriving on these shores and claiming the continent for the British Crown. At each of these times, the nation has been gripped by an identity crisis of sorts and has questioned the importance of these markers. There is a dissonance between the dominant storytelling and myth-making and the oft-ignored truth of who we are as a country.

Lawyer, academic, land rights activist and founder of the Cape York Institute for Policy and Leadership Noel Pearson, in his Declaration of Australia and the Australian People, talks of the three pillars that underpin our national story — the existence of the longest continuous culture on Earth; the British colonial project; and one of the most multicultural and multiethnic societies on the planet — and how each of these three pillars should be honoured as fully as possible. Although these narratives are part of the anecdotal, everyday experience of every Australian, they seem to be in conflict when elevated to the level of official national storytelling where they often fight for dominance. They tend to shout each other down and drown out one another’s legitimacy. By extension, until our public narratives can express the lived experiences of citizens, this dissonance will continue to unnerve and create ruptures rather than reconciliation.

First Nation artists have been playing a dynamic role in giving voice to the struggle and in building a stronger engagement by all Australians in the acceptance of First Nation knowledges and sovereignty, leading the way in reshaping museum collections, reframing colonial paradigms and rescuing institutions from irrelevance by asserting our cultural perspectives, histories and practices. Framed by these two significant colonial anniversaries of 1988 and 2020, I want to mark some of the high-profile contributions made by artists in shaping the modern public discourse in Australia.

1988

It is true to say that Australia really did not know what it was meant to be ‘celebrating’ on 26 January 1988, the bicentenary of the 1788 landing of the First Fleet in Botany Bay and Sydney Cove on Bidegal and Gadigal Country. The manufactured importance around the ‘celebration of a nation’ led to a number of artistic developments where First Nation peoples expressed their presence through demonstration.

In 1987, as advertisements were hitting the airwaves promoting the colonial milestone, a group of artists established Boomalli in Sydney. Euphemia Bostock, Fiona Foley, Michael Riley (deceased), Tracey Moffatt, Jeffrey Samuels, Bronwyn Bancroft, Avril Quaill, Fern Martens, Arone Meeks and Brenda Croft were the initial members of the collective. Although it was not in response to 1988, the birthing of this collective was timely, and many members went on to have significant solo careers articulating powerful cultural voices.

I assert that much of the First Nation arts infrastructure that we see today had its roots in the period immediately before and after 1988. Five years later, in 1993, the United Nations declared the International Year of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, with the theme of ‘Indigenous peoples — a new partnership’. Many companies and programs were founded between 1988 and 1993,1 and add to this list the establishment of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) — which would go on to be a significant influence in funding arts and cultural projects — and the High Court’s Mabo and Wik Native Title decisions, and you get the sense that 1988 may have been more of a catalyst for greater introspection and analysis than the bicentennial celebration organisers had anticipated. It is no accident that the Queensland Art Gallery’s Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) was conceived during this period. The first APT occurred in 1993 and featured a cultural dialogue involving artists of the region, including First Nation Australian artists.2

1988’s year of ‘celebration’ was also a year of protest and cultural assertion. Australia Day — 26 January, Australia’s national day that marks the start of colonisation — saw some of the largest Aboriginal protests the country has ever experienced. While the protests were occurring outside, inside the Australian Pavilion at Expo ’88 in Brisbane, Oodgeroo Noonuccal and her son Vivian Walker created a controversial performance with The Rainbow Serpent Theatre, a multisensory show seen by millions of people. Around the country, artists created events and held rallies that demonstrated our survival, most notably the Survival Day Concerts held at Sydney’s La Perouse, then Waverley Park, before the event was rebadged as the Yaban Festival. These concerts became a regular occurrence across the country and provided a counter-narrative to Australia Day myth-making, which would continue for more than 30 years.

At this time, then art adviser in Ramingining, Central Arnhem Land, Djon Mundine approached a small group of senior artists for The Aboriginal Memorial project. The project grew to include 43 artists, both male and female, from Ramingining and its surrounds, commissioned by the Australian National Gallery to create 200 hollow log coffins, one for each year of European settlement, representing the final rites for all Indigenous Australians who have been denied a proper burial. The Memorial was initially shown at the Biennale of Sydney in 1988, then brought to Canberra where it is now permanently housed in the National Gallery of Australia (NGA).3

1988 also saw the exhibition Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia open at the Asia Society Galleries, New York, to great acclaim; John Bulunbulun and other Arnhem Land artists win a court case over unauthorised use of their designs printed onto T-shirts; and the Barunga Statement presented to Prime Minister Bob Hawke by Galarrwauy Yunupingu and Wenten Rubuntja, which sought Indigenous rights and called on the Commonwealth Parliament ‘to negotiate with us a Treaty recognising our prior ownership, continued occupation and sovereignty and affirming our human rights and freedom’.4

The 1990s

While the late 1980s represented a statement of survival and saw us asserting ourselves into public storytelling, the 1990s was an exploration of identity and form. This was most markedly on display in performance work, where the narrative and the autobiographical gave way to the new, the abstract and the essentialised. The bevy of autobiographically inspired shows, such as Ningali (1994) by Ningali Josie Lawford and White Baptist Abba Fan (1997) by Deborah Joy Cheetham, and storytelling works like Funerals and Circuses (1992) by Magpie Theatre Company and Praying Mantis Dreaming (1992) by Bangarra Dance Theatre, were the natural inheritors of the groundwork done by Bob Maza, Jack Davis, Eva Johnson, Bobby Merritt, Kevin Gilbert and others. From this foundation came a new breed of form exploration, including Bran Nue Dae (1990), The 7 Stages of Grieving (1996) and Ochres (1994), among other productions.

Artists like Laurie Nilsen, Marshall Bell, Ron Hurley and Richard Bell — alongside Michael Eather and others of Campfire Group, Brisbane, and in parallel with Judy Watson — helped develop art that encapsulated the politics of the day and continued to give a voice to assertion and protest. Like Boomalli in Sydney and Tandanya in Adelaide, Campfire helped create a critical framework for the appreciation of a contemporary Indigenous voice through art. Training programs, discourse and sometimes straight-out argument helped to create an informative dialogue between First Nation artists and the status quo.

Campfire Group / Australia 1992– / All stock must go 1996 / Installation and performance event comprising truck, tent, artworks, merchandise, video, mixed media, for ‘The Second Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT2), Queensland Art Gallery, 1996 / Collection: The artists / Image courtesy: QAGOMA

Campfire Group / Australia 1992– / All stock must go 1996 / Installation and performance event comprising truck, tent, artworks, merchandise, video, mixed media, for ‘The Second Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT2), Queensland Art Gallery, 1996 / Collection: The artists / Image courtesy: QAGOMAIn Brisbane, the growth of this Indigenous artistic voice cannot be separated from the state’s political landscape. With the end of National Party rule in late 1989, there was a wholesale implementation of the Fitzgerald Inquiry recommendations and a shift in the lived experience for Indigenous Queenslanders. Not all obstacles disappeared overnight, but alternate voices emerged in music, art and politics.

In 1990 Rover Thomas and Trevor Nickolls became the first Aboriginal artists to reperesent Australia at the Venice Biennale, and in 1993 The Art of George Milpurrurru opened at the NGA — the first major survey exhibition of an Aboriginal artist in an Australian public gallery — and Aratjara: Art of the First Australians began a tour of major European art galleries, promoting Indigenous art with influence overseas.

For at least the past 50 years, there has been ongoing debate about the use of the terms ‘contemporary’ and ‘traditional’ when it comes to talking about Aboriginal art. This artificial dichotomy strengthens a ‘museum’ view of our work and sets notions of authenticity and contemporaneity into conflict — implying that somehow you cannot be both traditional and in the present day. Often ‘traditional’ has come to mean something from long ago that has been collected and perhaps repeated, whereas ‘contemporary’ is less about inherited practices and more about the politics or borrowing of Western forms. This is, of course, illogical as artists use inherited styles, stories and practices in the recent era all the time; some examples include Wukun Wanabi and the telling of his inherited story of fish and landscape using virtual reality and projection; Megan Cope and her use of materials and mapping; and Nellie Coulthard with her vibrant conversations with Country.

Wukun Wanambi / Marrakulu, Dhurili people / Australia b.1962 / Wawurritjpal (Larrakitj) 2017 / Purchased 2017 with funds from Pamela, Michael and Jane Barnett through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Wukun Wanambi / Photograph: Natasha Harth

Wukun Wanambi / Marrakulu, Dhurili people / Australia b.1962 / Wawurritjpal (Larrakitj) 2017 / Purchased 2017 with funds from Pamela, Michael and Jane Barnett through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Wukun Wanambi / Photograph: Natasha Harth Megan Cope / Quandamooka people / Australia b.1982 / RE FORMATION 2016–19 / Purchased 2019 with funds from the Contemporary Patrons through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Megan Cope / Photograph: Natasha Harth

Megan Cope / Quandamooka people / Australia b.1982 / RE FORMATION 2016–19 / Purchased 2019 with funds from the Contemporary Patrons through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Megan Cope / Photograph: Natasha HarthThere is a weird self-serving white concept that ‘real’ Indigenous people and their ‘true’ culture has died out. Many in Australia invest in this narrative to avoid addressing sovereignty, the effects of colonisation and the lie of terra nullius. By distancing authenticity from a contemporary experience, the works of living First Nation artists can be dismissed, lessened or placed in an alien context to the present. Over decades, we have witnessed over and over again the power of language, labels and terms to place us in a framing not of our own construction.5 Culture is neither static nor trapped in a glass display case, and artists are constantly responding, evolving, innovating and adapting to the world around us. Ultimately, this fluidity demonstrates the shapeshifting nature of our survival as we demonstrate our cultural continuity.

The legendary exhibition ‘Who Do You Take Me For?’ at Brisbane’s Institute of Modern Art (IMA) in 1992, curated by Clare Williamson, placed identity squarely at the centre of debate. Urban legend goes that Tracey Moffatt was invited by Williamson to take part in a group show exploring issues of cultural identity. There was robust correspondence between Williamson and Moffatt, exploring the ideas and complexities of identifying as an ‘Aboriginal’ artist, with particular regard to the categorisation of works in the exhibition — or, in fact, of the artist herself. Moffatt chose not to participate in the show; however, the correspondence was installed as part of the exhibition, demonstrating the robust debate around the politics of skin and art.6

The 2000s

The 2000s witnessed the maturation of a number of approaches to work and the value of exploring how we can take back the conversation. If we accept, as Toni Morrison believed, that all art is political, we can see the rise of both overt and covert commentary on racism throughout this period. These practices are not contained to the 2000s, but, like all movements, germinated from seeds sown decades before.

Brisbane’s proppaNOW collective has inherited much of the work started by Campfire Group (established 1992), and artists Laurie Nilsen and Richard Bell were joined by the next generation of artists who have been nurtured and supported through a plethora of opportunities. Vernon Ah Kee, Tony Albert, Jennifer Herd, Gordon Hookey, Bianca Beetson and Megan Cope helped to establish a discourse that recognises we are established — ‘proppa now’ — and should be taken seriously. This collective is diverse and in many ways pulling in different directions, but its artists drive each other to success. Like Boomalli’s artists, many proppaNOW members go on to have solo careers, and new members are welcomed to the group over time.

As part of wrestling back the narrative, we see artists engaging with museum and anthropological collections to recast the debate and point of view. Artists such as Fiona Foley and Brook Andrew find themselves delving into museum archives and recontextualising materials collected or catalogued by white anthropologists. It is arguable whether these museum collections hold accurate records of encounters due the fact that they can only ever be one-sided. There are so many stories of white anthropologists who get it wrong as a result of translation issues; from having limited access to the full story due to gender or initiation rites; or even because those being interviewed were wilfully making fun of them. In a modern context, this was played out in the naming of Moomba community festival in Melbourne in the 1950s. Bill Onus, father of artist Lin Onus, famously offered up the Kulin word ‘Moomba’ to festival organisers. Unbeknownst to them, the word means ‘bum’ or ‘I can see your bum’ or ‘up your bum’. There is wit and charm in such a retelling of history, and artists who engage with archives are bringing a First Nation voice to life to reflect oral traditions. Wiradjuri performance artist Joel Bray is currently undertaking a similar journey in reviewing ceremony and recasting public performance.

On a parallel path to the museum archival practice, it is interesting to look at the recasting and exposing of Aboriginal popular kitsch, or Aboriginalia, that can be traced back to the times of Albert Namatjira and before. Artists are fascinated with how we have been seen historically, as well as repulsed and excited by the commercial interpretation in Australian domestic decoration. Photographer and media artist Destiny Deacon is the queen of this tongue-in-cheek, yet searing, investigation of race and identity. Alongside Deacon is Tony Albert, who also explores our lived experience with these objects. There is a mix of pride and dismay to be found in the fascination with Aboriginalia that acknowledges our presence in this Country, but somehow still controls the way we are seen. Taking popular and ubiquitous designs — ashtrays, tea towels, velvet paintings, playing cards, dolls, souvenir spoons and the like — and reappropriating their images is an intriguing counterpoint to official records of engagement. In many ways, they are two sides of the same coin of the control of representation, the popular and the official, and both are treated with irreverence and respect as they inform new works and ways of seeing.

Similarly, there are practices that go unnoticed or under-appreciated, especially when it comes to community practice and documentation. Given the lack of our voices in official records, it is often left to our artists to document our events and actions for the public archive. Veteran photographer Mervyn Bishop shows us the power of the image in terms of the famous and the ‘newsworthy’, but many artists continue a community practice that can only give meaning to events or personalities retrospectively. Barbara McGrady was recently featured at the 22nd Biennale of Sydney, NIRIN (2020) where her work demonstrated how the accumulation of meaning over time can be powerful and overwhelming. In Melbourne, the name Lisa Bellear is synonymous with a collection of thousands of images from community events that mark a practice and engagement celebrating the local personalities and important moments in time. Similarly, in Brisbane, Jo-Anne Driessens documents untold stories not for commercial return, but as a practice of engagement and creating the archives of the future.

Barbara McGrady (with John Janson-Moore) / Gomeroi/Murri/Yinah peoples / Australia b.1950 / Ngiyaningy Maran Yaliwaunga Ngaara-li (Our Ancestors Are Always Watching) (installation view) 2020 / 22nd Biennale of Sydney (2020), Campbelltown Arts Centre, Sydney / Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous support from the Australia Council for the Arts / Courtesy: Barbara McGrady / Photograph: Zan Wimberley

Barbara McGrady (with John Janson-Moore) / Gomeroi/Murri/Yinah peoples / Australia b.1950 / Ngiyaningy Maran Yaliwaunga Ngaara-li (Our Ancestors Are Always Watching) (installation view) 2020 / 22nd Biennale of Sydney (2020), Campbelltown Arts Centre, Sydney / Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous support from the Australia Council for the Arts / Courtesy: Barbara McGrady / Photograph: Zan WimberleyThe 2010s

We are the inheritors of those who have gone before us.

Despite the dismantling of ATSIC, the denial of the Stolen Generations and the attempted derailing of the Reconciliation movement in the 2000s, political changes by the end of the decade prepared the way for some shifts in decision-making and control. By the 2010s, many of the self-determination goals we had been fighting for came to fruition.

Public art and events have become an exciting frontier for the participation of First Nation artists. Large-scale sporting events, civic construction and public art installations have allowed many artists to move from a gallery practice to embrace the epic and the monumental. Jonathan Jones’s barrangal dyara (skin and bones) 2016 is a stand-out work in terms of its impact and power to affect the public storytelling of a city. Reko Rennie successfully translates his street-art background into massive interventions in the landscape, highlighting the need for a collective memory of dispossession and colonisation. Architectural and sculptural works by Alick Tipoti (aided by Urban Arts Projects) and works by Australian artists commissioned for the Musée Du Quai Branly in Paris — as well as the practices of Brian Robinson, Judy Watson, Fiona Foley and Jacob Nash — all demonstrate a shift in the size of the canvas, and address the discourse of memorials, monuments and public spaces.

Jonathan Jones / Kamilaroi/Wiradjuri people / Australia b.1978 / barrangal dyara (skin and bones) (installation view) 2016 / Kaldor Public Art Project 32, Royal Botanic Garden Sydney / Gypsum, kangaroo grass (Themeda triandra), eight-channel soundscape of the Sydney Language and Gamilaraay, Gumbaynggirr, Gunditjmara, Ngarrindjeri, Paakantji, Wiradjuri and Woiwurrung languages / Dimensions and durations variable / Courtesy: The artist and Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney / Photograph: Peter Greig

Jonathan Jones / Kamilaroi/Wiradjuri people / Australia b.1978 / barrangal dyara (skin and bones) (installation view) 2016 / Kaldor Public Art Project 32, Royal Botanic Garden Sydney / Gypsum, kangaroo grass (Themeda triandra), eight-channel soundscape of the Sydney Language and Gamilaraay, Gumbaynggirr, Gunditjmara, Ngarrindjeri, Paakantji, Wiradjuri and Woiwurrung languages / Dimensions and durations variable / Courtesy: The artist and Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney / Photograph: Peter Greig Judy Watson / Waanyi people / Australia b.1959 / tow row 2016 / Commissioned 2016 to mark the tenth anniversary of the opening of the Gallery of Modern Art. This project has been realised with generous support from the Queensland Government, the Neilson Foundation and Cathryn Mittelheuser AM through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Judy Watson / Photograph: Natasha Harth

Judy Watson / Waanyi people / Australia b.1959 / tow row 2016 / Commissioned 2016 to mark the tenth anniversary of the opening of the Gallery of Modern Art. This project has been realised with generous support from the Queensland Government, the Neilson Foundation and Cathryn Mittelheuser AM through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Judy Watson / Photograph: Natasha HarthWe have come a long way and we have seen seismic change in the nature of engagement since 1988, but as we faced the COVID-19 pandemic and the Cook anniversary, it was interesting to see the shifts in discussion. We have changed a lot, but maybe not enough. Invasion Day, 26 January, has become the most contentious date in the Australian calendar, and any talk of James Cook statues can earn you scorn and derision — as Australian television news and political journalist Stan Grant found out — and I fear there is a conservative backlash settling in that could undermine the hard-fought victories of the past 30 years. This is the time to engage and have your voice heard. Thirty years is not a long time in the face of 30 000 generations, and if I have learnt anything, it is that artists play a role in shaping the future and remembering the past. Artists are the storytellers of the tribe and we must play the role our communities ask of us.

To this end, I leave you with Tony Albert’s You wreck me 2020, his cheeky response to the Cook anniversary. Maybe there is a lesson here — to be cheeky, brave, present and inventive, to give shape to the inarticulate, so we can face the world head-on.