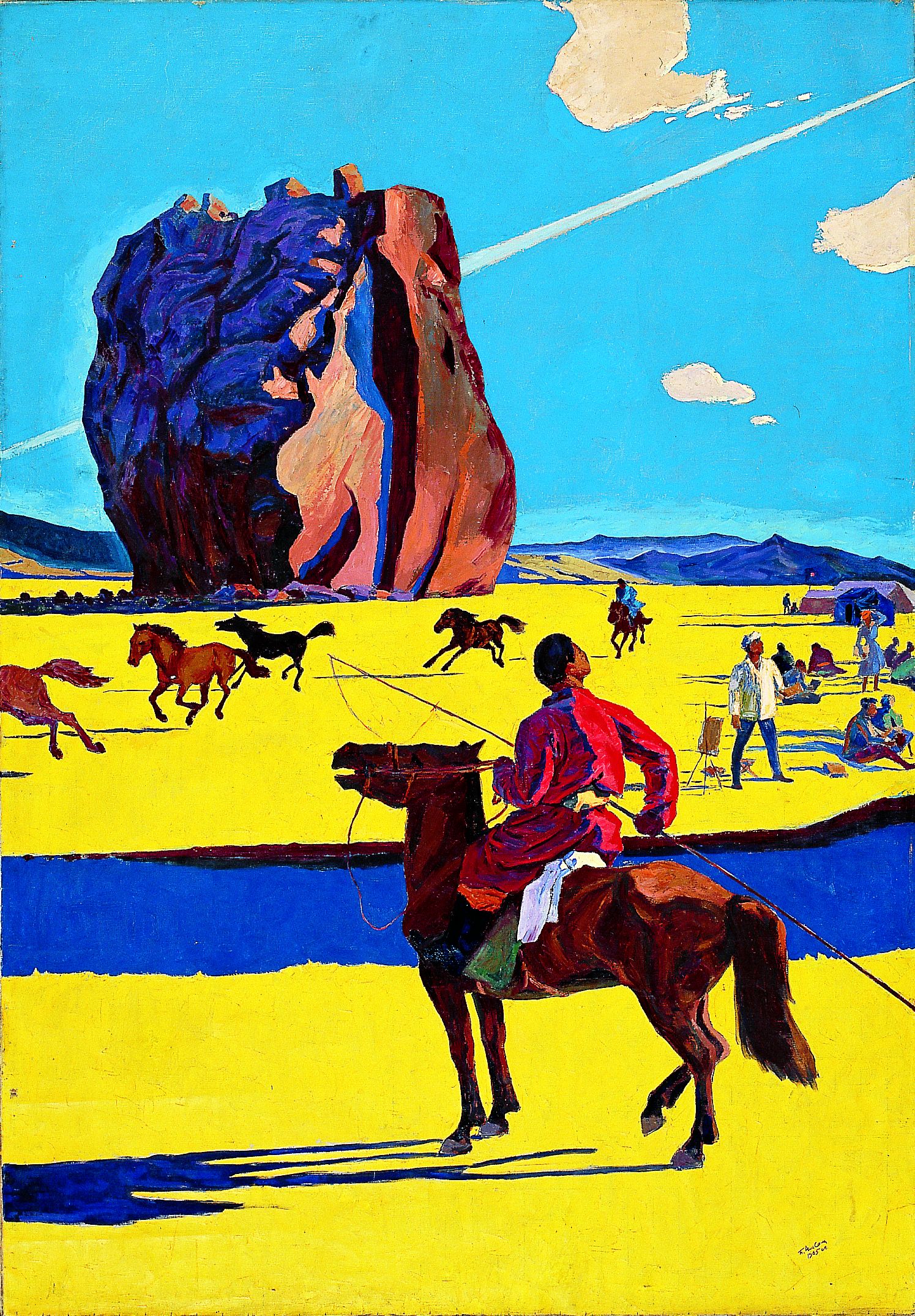

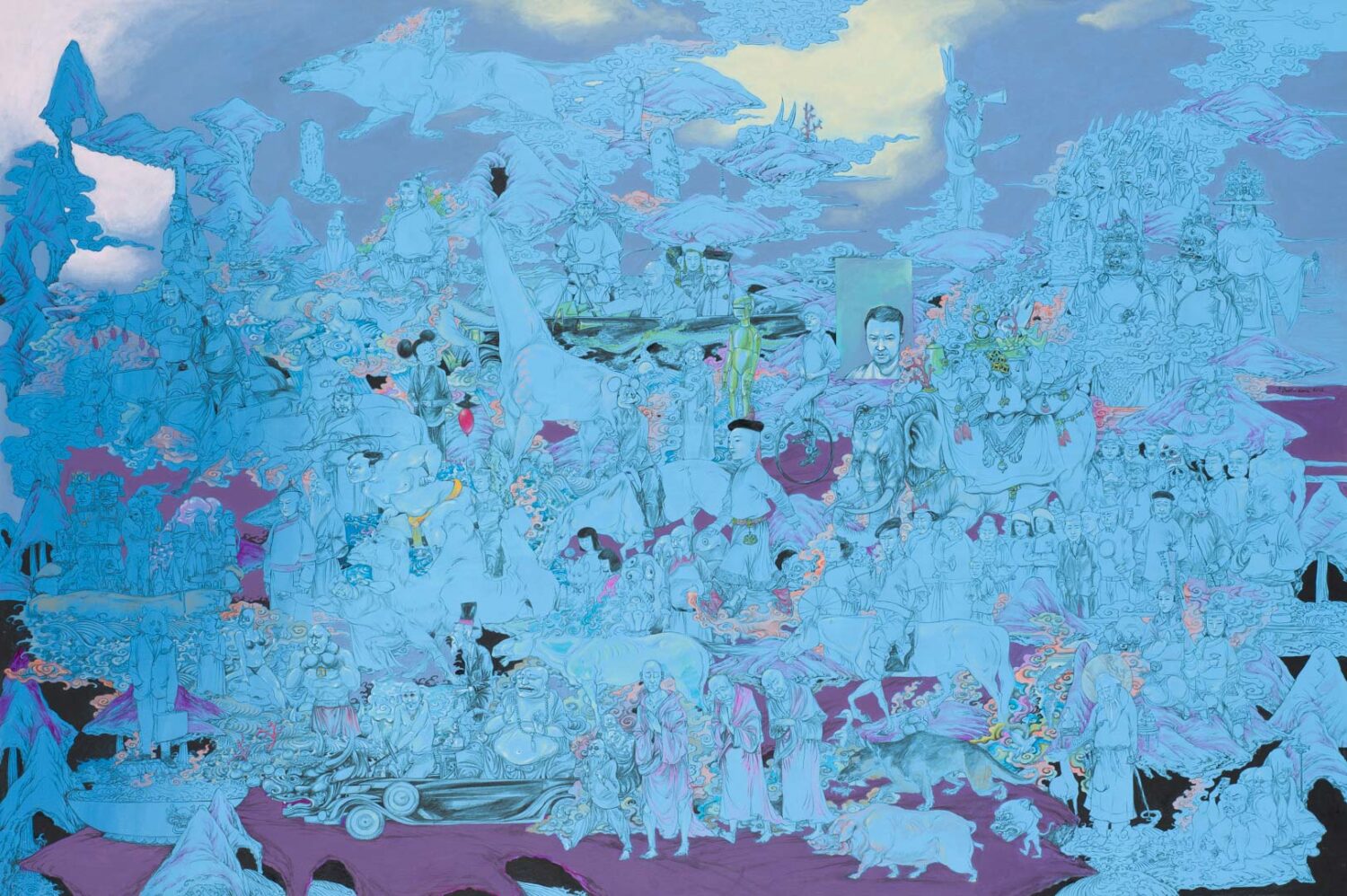

Batjargal Baatarzorig / Mongolia b.1983 / Nomads 2014 / Synthetic polymer paint on canvas / 100 x 150cm / Purchased 2015. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation Grant / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Batjargal Baatarzorig

Batjargal Baatarzorig / Mongolia b.1983 / Nomads 2014 / Synthetic polymer paint on canvas / 100 x 150cm / Purchased 2015. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation Grant / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Batjargal BaatarzorigThe era of uncertainty and the roots of modern art in Mongolia

The twentieth century was a turbulent era around the world with two World Wars and an ideological Cold War lasting until its final decade. Mongolia, where Buddhist culture prospered until the late 1920s, became an ally of the Soviet Union, where the majority of Mongolian modern artists were trained. These artists returned with the new media of oil and canvas, European art conventions of linear perspective, the realistic style and anatomical modelling of figures, as well as new genres and institutions of art (Fig.1). Akin to many other eastern bloc countries, artists were censored, and the Soviet Union endorsed Socialist Realism as the main style to be followed. Modernism was not completely disallowed, however, and even as early as the 1960s and throughout the socialist period, artists, such as B. Chogsom, Ch. Bazarwaan, Do. Bold and S Tugs-Oyun, among others, worked with modern styles (Fig.2). Very few experiments were made in non-figurative art, with abstraction discouraged in 1969 and denounced as ‘capitalist art’ (Fig.3).1

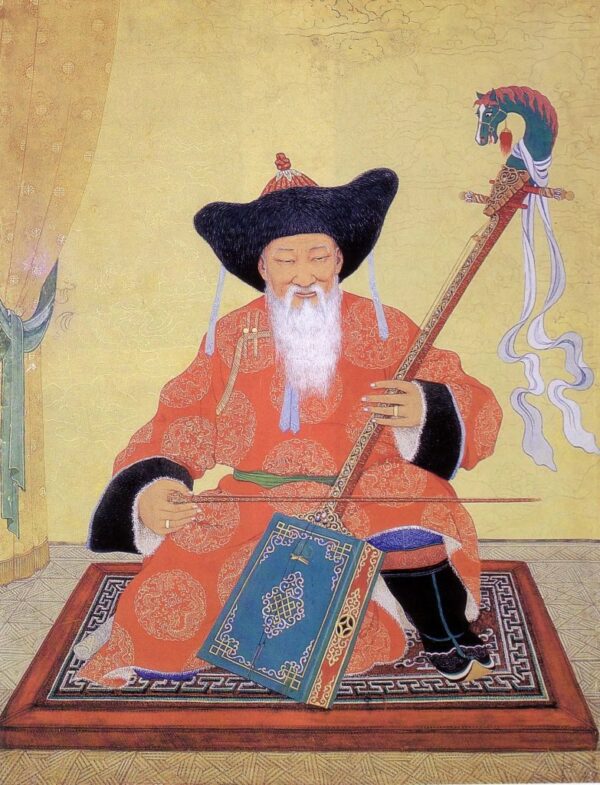

Due to the demolishing of Buddhism by the socialist leaders — who also heavily restricted the study of history by replacing traditional Mongolian script with the Cyrillic alphabet — Mongolian intellectuals and artists were challenged to apprehend the new reality of Sovietisation. Consequently, under conditions similar to those which brought to creation nihonga in Japan and guohua in China, Nyam-Osoryn Tsultem (1923/24–2001) was instrumental in the invention of a new Mongolian style that would serve as a visual language for Mongolian identity. One of the early works in this intellectual conversation was Ü Yadamsüren’s Epic Teller (Fig.4), where the medium is similar to that of a thangka painting, and the flatness of the depiction and decorative texture of the pictorial surface has been maintained (in contrast to European realistic style). Trained in Moscow and alarmed by Soviet intellectual oppression, Nyam-Osoryn Tsultem was active in the movement to preserve Mongolian culture as he stood against Sovietisation. In his prominent works, such as Appeal (Fig.5) and Ensemble of Clouds (Fig.6), Tsultem depicts a revolutionary hero blowing a conch, presumably a call to arms; in the latter, he shows a composition dominated by ornamental clouds. However, the motifs, the flatness and decorative texture are all borrowed from Buddhist thangka painting.

Mongolian artists and globalisation

The question of Mongolian identity remained throughout the twentieth century and continued into the new millennium. If, in the twentieth century, it was about preserving the culture and heritage against Sovietisation, when democratic reforms started and a new multi-party government was established in 1992, a new era of art began in Mongolia. Western contemporary art was unknown, and several ‘new art’ associations, such as Green Horse, Sita Art, Ego Art, New Art Association, were organised by different groups of artists to promote freedom of expression in visual arts with a particular emphasis on Western contemporary art media of installations. The majority of Mongolian artists, and the public, were completely unaware of artistic approaches or media outside figurative depiction. Yo. Dalkh-Ochir, M. Khuyag-Ochir and G. Erdenebileg were among only a few Mongolian artists who established an art dialogue with Western European artists to exchange or share joint exhibitions and workshops.

A transition from a censored socialist realism to a Western multimedia art was uneasy and confusing throughout the 1990s, as artists were engaged in experimentation with the new media and non-representational styles discouraged during the socialist era, in order to explore their own creative voice in a new political system with freedom of expression. Another outstanding question in Mongolian contemporary art is the favour and advocacy for the conceptual approach as a distinct hallmark of what ‘contemporary art’ is about as currently understood among the artists. In the 1990s, when Western contemporary art media was also introduced, installations, performance art, video, and photography, collage and assemblage works were completely unknown to both Mongolian artists and the audience.2

Some artists of the Green Horse Society, such as Yo. Dalkh-Ochir, G. Erdenebileg or M. Khuyag-Ochir of the Sita Art Society were among the first installation artists in Ulaanbaatar whose works were both intriguing and hard for the audience to understand. Regardless, they inspired many followers; even such artists as S. Dagvadorj, who were trained as painters, arranged their solo shows with monumental installations using elements of the yurt (Mongolian: ger). Dagvadorj’s participation in the Gwangju Biennale in 2000 showed an installation of stirrups tied onto long vertical ropes hanging (symbolically) between sky and earth. It won the Biennale’s prize.

Browsing through the abundance of possibilities, other artists looked into the questions that explore identity and assist in searching the self and belonging in the new era of multi-party government and a market economy. Many male artists, such as Sh. Chimeddorj, M. Erdenebayar (Fig.7) and others, took the horse as their main motif, as the figure of the horse is considered the ‘window’ onto the search for the inner self. At his solo exhibition at Hong Kong’s Hanart TZ Gallery in 2016, Chimeddorj showed horses within historical themes that also included titles such as The Great Mongolian Empire, as represented by a horse, and Khitan Huntsman, referring to the Liao dynasty in the tenth century, represented by a horseman and horse (Fig.8).

This retrieval of the past is ongoing — not only among artists, but across the entire Mongol society, as we see in this monumental, 40-metre equestrian statue of Chinggis Khaan right outside of Ulaanbaatar. The name of Chinggis Khaan had not been allowed — not even to be pronounced — during the socialist era. And now, with this newly obtained freedom of expression, so many good and bad, mediocre and ugly paintings, sculptures — including all kinds of works representing Chinggis Khaan — are being made in Mongolia. Even ‘Chinggis Khaan’ vodka! These are all part of the country’s painful efforts to understand its own past and reconnect with its heritage.

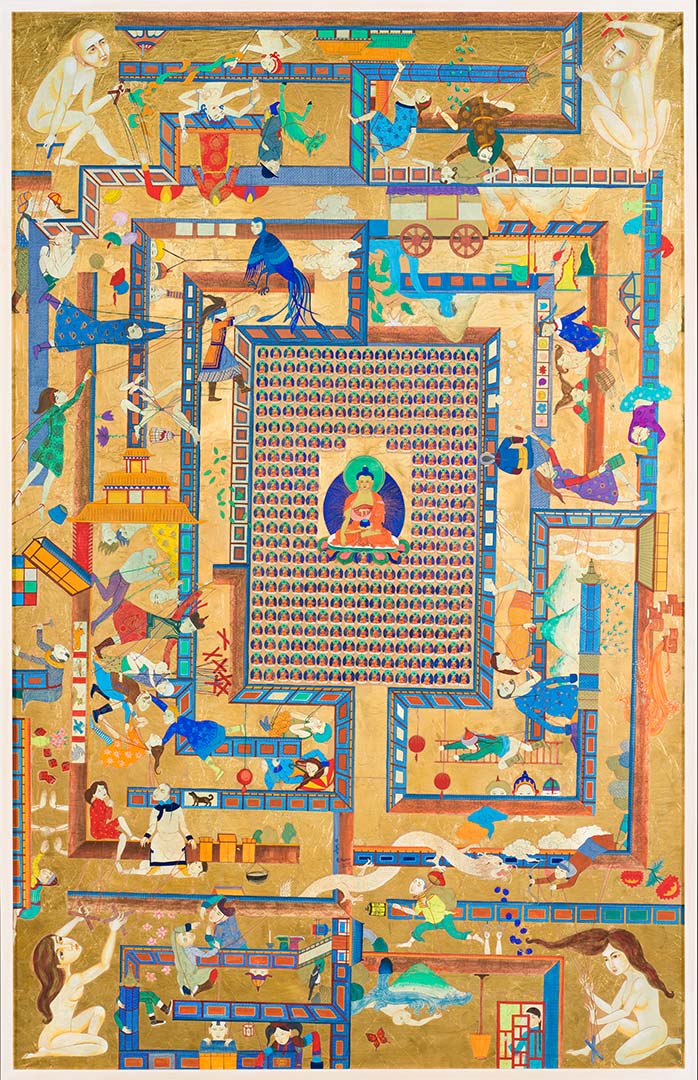

One direction in exploring of the past was taken by Ch. Baasanjav in 2009, when he began using Buddhist motifs and iconographies in his non-Buddhist paintings, through which he aimed to critique disasters of the neoliberalism that had already formed in Mongolia. Trained in Mongol zurag style. Baasanjav’s work The Taste of Money In-Between Clouds (Fig.9) was a pioneering work of the trend that began to look at art as a platform for critiquing the ills that were happening in neoliberal Mongolian society: corruption, privatisation of land, environmental issues surrounding mining. Placing a central, dominant figure of a man in a black suit, whose newspaper that reads ‘Truth, Today’ in Cyrillic, and who clutches dollar bills, an axe in his multiple hands, Baasanjav takes aim at corrupted politicians and business people.3 The composition borrows motifs and elements from Buddhist paintings, but, recalling previous efforts of a similar kind in the past century (Fig.5), they are completely transformed and appropriated to create a new context for their new meaning. Juxtaposing a scroll with the Mongolian traditional vertical script that reads, ‘Please leave to us those who belong to mountains and rivers, our virgin land, and our flowing river!’ against the Cyrillic inscription of modern-day Mongolia, Baasanjav not only clarifies the critical message of environmental issues in his work, but more significantly, reminds us of Mongolia’s efforts to reclaim its identity through tradition and the retrieval of the past. Baasanjav, B. Baatarzorig,4 B. Nomin (Fig.10), O. Urjinkhand, Sh. Tamir and others followed this trend with their paintings in Mongol zurag style, which continue the transformation of Buddhist iconographies into explicit critiques of neoliberalism. Among artists, Baatarzorig suggests that Mongolia is ‘lost in translation’ among the rapid import of Western and East Asian popular cultures, which feed Mongolian audiences hungry for information and connections with the world (Fig.11). Prior to these works, B. Orkhontuul emerged and had established himself among artists whose acute presentation of societal problems made it possible to relate to art at a different level (Fig.12).

Orkhontuul is a member of a new contemporary art group the Blue Sun Society, organised by Dalkh-Ochir and his followers, who continue to propagate and work almost exclusively in multimedia and advocate a conceptual approach in contemporary art. They organise group exhibitions, international exhibition-exchange projects, art-camp residence travels involving camping and exploring different natural locations to produce land art (Fig.13), which they document with video and photography later exhibited in museums in Ulaanbaatar.

One of the Blue Sun artists is T. Enkhbold, who stages his ‘mobile homes’ across the continents at different locations. His first minuscule yurt, built by hand, as a light and portable ‘mobile home,’ was erected on the beach, right at the borderline between the water and land in Rotterdam in 2009 (Fig.14). In 2011, Enkhbold went to Jeju Island and built another ger, again at the borderline between the sea and the land. The yurt is a land dwelling, architecture built for living on the steppe, and is still used by Central Asian nomads in general, and even now, a considerable portion of Mongolia’s population still lives in them. As Enkhbold builds his homes — structures designed specifically for steppes — in highly unusual locations, which visually contrasts the yurt’s minuscule size vis-a-vis sites of monumental scale and radical difference, Enkhbold explores the profoundly human questions of home, belonging, identity and displacement in the modern world.5 Recalling performance works by earlier Asian artists in New York and elsewhere, Yayoi Kusama’s Walking Piece New York, for instance, Enkhbold has deliberately turned his ger into a visual statement of his otherness by erecting it in front of a museum, a medieval cathedral, nearby a freeway or on a street in Venice (Fig.15). As he places the sign ‘Welcome to My Home’ in front of his tiny construct, he is explicit about the participatory nature of his performance; it is shaped through team effort and evolves through the spontaneity of communication with the visitors inside of his home. Akin to participatory performative works by other Asian artists, such as Thai Rirkrit Tiravanija and Lee Mingwei of Taiwan, whose art invites active engagement from the audience, Enkhbold’s performances are based on the idea of communication and connection. By his intentional use of spontaneity and otherness as the foundation upon which he interacts, and inviting communications from his random audiences, Enkhbold defies the boundaries placed by citizenship and other forms of sociopolitical association. He celebrates and proclaims his otherness as a part of globality, and through spontaneous, unplanned, sheer human connectedness, he activates ‘a view of human subjectivity that is relational’.6 These communications contribute to the process of subject formation, in which ‘otherness is excluded by definition’.7

Another artist who defies the borders of local–global is A. Ochirbold, who regularly participates in Germany’s Nord Art Festival with his monumental sculptures and installations. While his participation in Mongolian group exhibitions began in 2009, his first solo show, titled ‘Consciousness’, took place in Ulaanbaatar in 2014, where he explored identity and ‘Mongolianness’ through the materiality of Mongolian nomadic culture. However, his questions in his recent works reach beyond the localisation of culture and trigger thoughts of humanity, and of being human in our turbulent era. His public sculpture, Consciousness, installed in New York in 2017 (Fig.16), shows a slim figure of a standing (fe)male built of metal wires with the feet firmly pressed into a shiny, mirror/pond-like platform. Balancing between the verticality of the figure and the slight degree of its forward lean, the viewer’s gaze is directed at the self projected in the mirror. A pair of a footprints suggest a silent or (in)visible presence of the others here; meditating and balancing, with feet rooted into the mirror, the figure leans forward, suggesting a deep, undisturbed moment of self-reflection and mindfulness. Ochirbold used this form in numerous installations, as recently as during the global pandemic in Ulaanbaatar, and in a group exhibition titled ‘Spirit of Gobi: Consilience’, organised by MN17 Gallery in the Gobi Desert (Fig.17).

Even in these outdoor installations, Ochirbold’s Consciousness generates new meanings, offering a sense of immediate concern and menacing reality for humankind, particularly potent during this era of global pandemic. ‘Spirit of Gobi: Consilience’, which bridged a music concert with visual arts in the Gobi Desert, was another prominent outdoor event that urged and inspired connectedness in creativity. The exhibition featured such important contemporary artists as D. Dorjderem (whose work Voice in the Space (Fig.18) won the Signature Art Prize in the category of People’s Choice Award at Singapore Art Museum in 2008),8 G. Gerelkhuu, B. Baatarzorig, D. Bat-Erdene, B. Nomin and Ts. Ariuntugs, the latter two also being involved in Documenta 14 in 2017.9 These artists demonstrate their works to explore the complexity of realities of modern Mongolia and beyond (Fig.19).

Mongolianess in these artists’ works is subtle, nuanced and complex; it is not simplified with the stereotypical lens of ‘what sells’. Even in two-dimensional works, where the more conventional media of oil on canvas is applied, artists such as Ts. Enkhjin show multi-layered compositions (Fig.20), in which figures are intentionally superimposed to further the debates on questions of global significance, such as gender, sexuality, social status, and modernity’s relation to the past — here, placed in the context of Mongolia. Enkhjin provides another example of a multivalent work with UH-! (Fig.21), which, recalling the abovementioned artists, discourages thinking of Mongolia through the stereotypical lens, instead helping viewers relate to the complexity of ‘Mongolianness’ through universal questions of global concern. As Rosi Braidotti has put it,

the simultaneity of our being in the world together sets the tune for the ethics of our interaction … [as it] requires us to synchronise the perception and anticipation of our shared, common condition.10

A growing number of artists working in photography and video, such as Ariuntugs, Tuguldur and Ganzug, enhance the Mongolian artists’ quest for globalism. Ariuntugs’s Unnameable Manufacture #8 (Fig.22) consists of forests, trees, and a sharp saw. Even though there is nothing explicitly Mongolian shown (like ‘throat singing’, for example), the significance of this specific object in the video, according to Ariuntugs, comes from the countryside, where there is a belief among the nomads that a saw placed at the threshold of a yurt protects their household. Within the entire composition, it is clear that Unnameable Manufacture #8 is about environmental issues beyond a single locale.

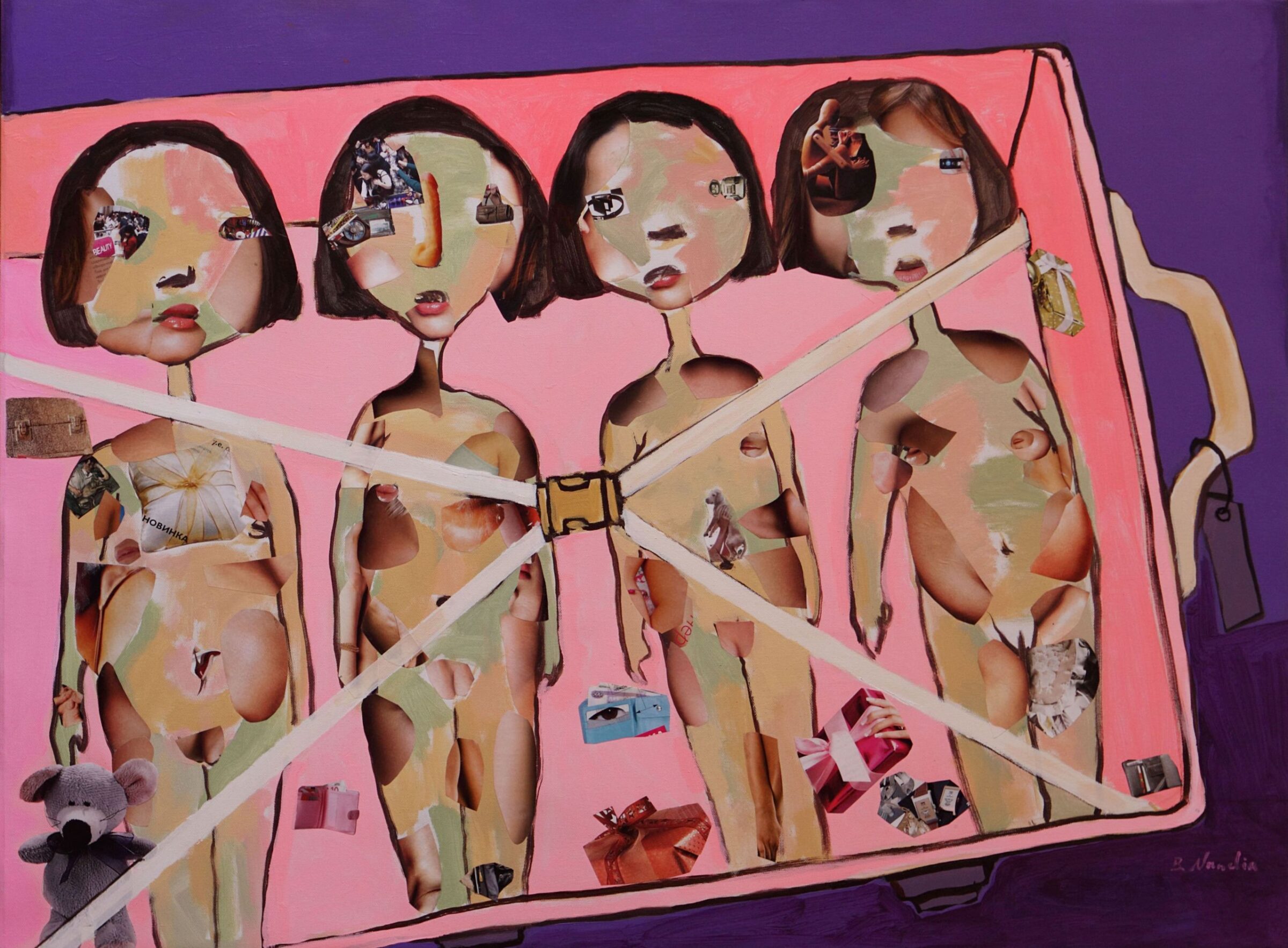

These issues are among those explored by an increasing number of women artists in Mongolia. As soon as socialist regime ended in 1990 and freedom of expression became unlimited, Ya. Bulgan’s main questions were focused on sensitive issues of the then-impoverished country, such as homeless children — young children forced to leave their abusive guardians and live on the streets, and orphans abandoned without shelter and abused on the streets. Bulgan was not alone; other women artists such as B. Nandin-Erdene followed suit by addressing acute problems of social welfare and the lack of strong laws and regulations to protect the vulnerable and underprivileged in the transforming society. Nandin-Erdene’s many works, such as Luggage 2009, Swinging Life 2012, Lost Body in Mirror 2017 and more, produced with mixed media of collage on paper or canvas, highlight the painful realities of the abuse and human trafficking of unprotected children (Fig.23). Bulgan and Nandin-Erdene’s mission is to address the indifference and omerta of society to bring awareness and make explicit those societal cruelties that minors — often underprivileged young girls — experience, in Mongolia in particular, but also elsewhere in the world.11 In addition to cases of explicit violence and cruelty, Mongolian women artists also direct our attention to the severe realities of motherhood, which include, according to Mugi, the protection of their babies and securing their healthy growth, and the reparation of the maternal body after pregnancy (Fig.24).12

These and many more Mongolian contemporary artists are truly multifaceted and dynamic as they continue to address pertinent issues of belonging and identity, the urge and need to recapture their vital past, and the many complexities of grappling with what is meaningful contemporary art. Only through an open-minded approach of multiple interdisciplinary perspectives, and the abandonment of dangerously singular and simplified views, can true knowledge of the flourishing art scene in Mongolia today be obtained for thorough appreciation.

This essay is based on a talk given for the Society for Asian Art at Asian Art Museum in San Francisco in March 2021. I thank the Society and its members for an invigorating discussion and questions. I also thank Reuben Keehan for inviting me to submit this essay for QAGOMA’s Asia Pacific Art Papers.