Rocky Cajigan / Ifontok and Kankanaey people / The Philippines b.1988 / Hairloom 2017 (detail) / Mixed-media site-specific installation / ‘Collective Memories’, The Drawing Room (Contemporary Art), Makati, Manila, Nov–Dec 2018 / Image courtesy: Rocky Cajigan

Rocky Cajigan / Ifontok and Kankanaey people / The Philippines b.1988 / Hairloom 2017 (detail) / Mixed-media site-specific installation / ‘Collective Memories’, The Drawing Room (Contemporary Art), Makati, Manila, Nov–Dec 2018 / Image courtesy: Rocky CajiganDespite centuries of colonisation having shaped the lives of the Philippines’ inhabitants, major components of indigenous Filipino cultures, social institutions and living practices remain. This is substantially true in the more remote regions in the country’s north and south, in the Cordillera and Mindanao, which for many years were categorised as ‘uncolonised’.1 Visual art forms — and particularly painting — inherited through Spanish occupation exist alongside vernacular and indigenous practices of weaving, carving and body adornment, and intangible cultural forms such as performance, music, dance and storytelling, often linked to spiritual beliefs and embedded in social customs and everyday life.

With over 110 ethno-linguistic groups spread across more than 7000 islands, conceptualisations of indigeneity in the Philippines are ‘contingent … [and] heterogeneous’.2 Successive waves of migration and geographical proximity to nearby nations have also led to substantial variations in culture, religion, language and ethnicity.3 Anthropologist Oona Paredes writes that, within South-East Asia in general, indigeneity is a problematic concept:

given its indigenous populations have experienced centuries of mobility, and the fact that, in most places, even the dominant or majority ethnic groups, with few exceptions, are recognised as native to the region. Indigeneity is therefore subject to specific cultural meanings at the local level.4

With the commencement of the Marcos era, indigenous and vernacular culture became important to a rhetoric of national identity and cultural patrimony in the Philippines.5 Since at the least the 1970s, Filipino artists including ethno-musicologist and artist Jose Maceda, Roberto Villanueva, Leonard Aguinaldo, Kidlat Tahimik and Kawayan de Guia, Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan, Cian Dayrit, and photographers Tommy Hafalla and Eduardo Masferré, have either been inspired by vernacular culture or established dialogues and collaborations with indigenous communities. Curators such as Marian Pastor Roces, Patrick Flores and Analyn Salvador-Amores have provided enlightenment on textiles, modes of dress, weapons, weaving, woodcarving and pottery. Yet divisions between indigenous and colonial, and between art and craft, remain. There is little agreement on what is acceptable ‘borrowing’ or referencing and what constitutes cultural appropriation.6

In addition, customary practices are infrequently positioned within a field of contemporary art, and a dearth of indigenous artists situating their practices in this way have had works shown in a gallery context outside the Philippines.7 To aid an understanding of the complexity of both situating and comprehending indigenous art in the Philippines, the following analysis explores the lives and works of three artists from the Cordillera region, from different backgrounds and generations, beginning with an artist who became an advocate and pioneer for the redefining of Filipino culture through the incorporation of indigenous voices and creative expression.

Drown my soul: Santiago Bose and the Chico River protests

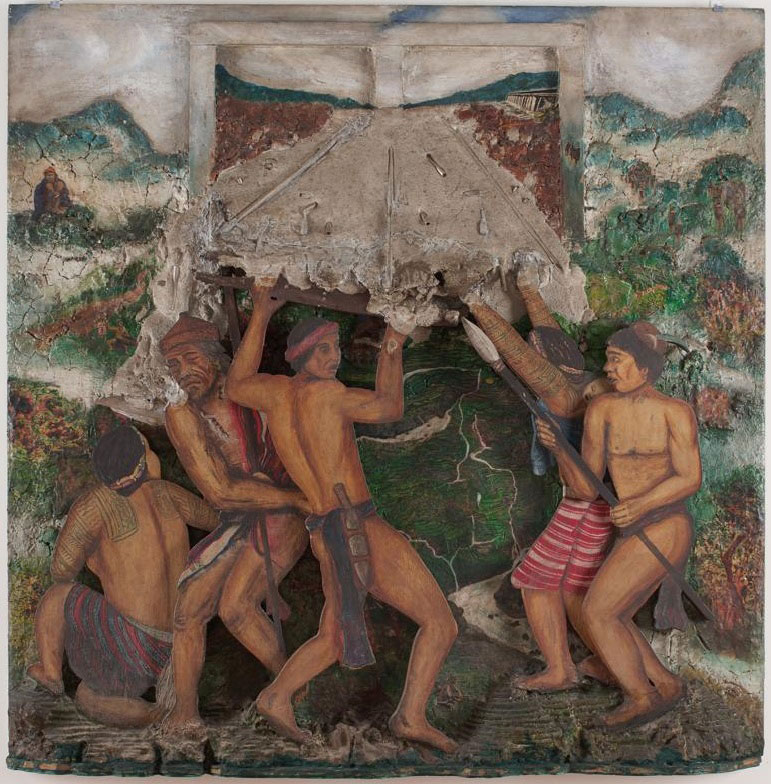

In Santiago Bose’s Drown my soul at Chico River (Bury my soul in Chico River) 1981, a small group of men and women are shown in a mountainous landscape, a kind of topographical map representing the area along the Chico River in the mountainous Cordillera region.8 Dressed in the distinctive woven garments of Kalinga people and with their bodies adorned with customary tattoos, they struggle to hold up a weight that bears down on them. The figures are created with wood reliefs so that their bodies stand away from the landscape, their feet appearing to slip on the muddy soil of the rice terraces as they strain against it.

Bose’s work celebrates the activism and bravery of the Kalinga people who, for more than 30 years, resisted the Chico River Dam Project proposed by the president, Ferdinand Marcos, during the period of Martial Law. Marcos enlisted support and funding from the World Bank to commence a vast hydro-electric project to dam the river, which traverses the Cordillera and Cagayan valley regions. If completed, the four proposed dams would have provided electricity for lowland areas, but at the cost of displacing hundreds of thousands of indigenous people in Kalinga and Bontoc, destroying villages, homes, livelihoods, ancient rice terraces, sacred sites and the river itself.

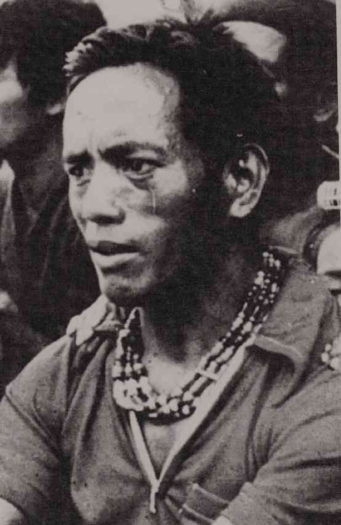

Although compensation for relocation was offered, it was rejected, with indigenous communities arguing that their anitos (ancestors) were present in the land, as were their systems of laws and beliefs. Macli-ing Dulag, a pangat (leader or respected elder) who became the activists’ official spokesperson, eloquently summed up the situation:

The question of the dam is more than political. The question is life — our Kalinga life. Apo Kabunian, the Lord of us all, gave us this land. It is sacred, nourished by our sweat. It shall become even more sacred when it is nourished by our blood.9

In notable events, Kalinga women performed a lusay, in which they stripped and revealed their tattoos to the men working on the dam — a bestowal of bad luck and ill fortune. When the shamed workers crept away, the women dismantled and burnt their encampments, setting the project back.10

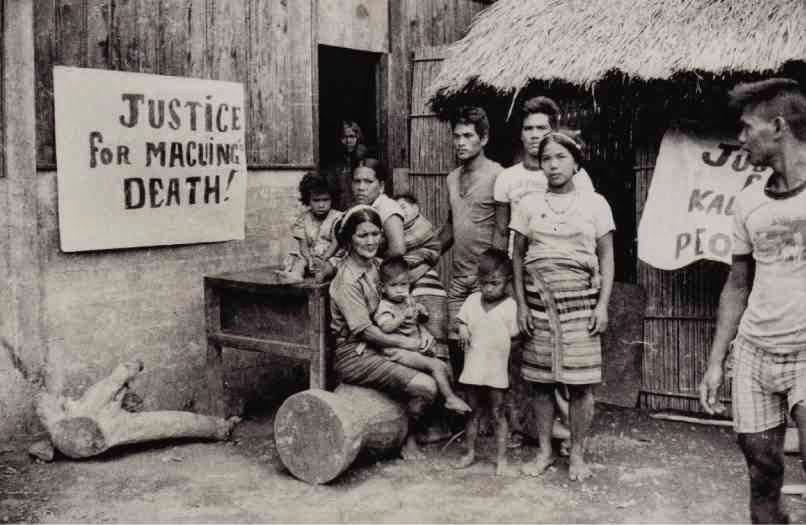

In 1980, Macli-ing Dulag was assassinated by the military in an attempt to stop the dissent to the Chico River project. Contrary to the expected outcome, the violence against Dulag served to unite the various indigenous peoples of northern Luzon (Ifugao, Bontoc, Kalinga, Isneg, Ibaloy, Tinngguian and Kankanaey, among others), collectively known as ‘Igorot’. When Bose briefly returned to the Philippines from the United States in 1981, the protests were still underway and the memory of Dulag’s death raw and recent. By 1986, the activists had successfully staved off the project in a landmark victory for indigenous rights and ancestral lands.11

Living and working in the US during the late 1970s and early 1980s, Bose — who had been in discussion with American artist and activist Jimmie Durham — was aware of increasing activism in minority groups like the Cherokee. With its title inspired by the influential book Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West (1970), which offered an alternative view of frontier histories through the accounts of indigenous Americans,12 Bose’s Drown my soul at Chico River illustrates the personal resonance for the artist of the Kalinga people’s political actions in the Cordillera. The work incorporates found objects, collage, assemblage and woodcarving, and is characteristic of Bose’s multimedia practice. Professor and art historian Alice Guillermo described Bose as a ‘tireless experimenter’ who would both discover and constantly invent new media for his work. Guillermo also touched on the communal and political concerns of Bose’s work, specifically mentioning Drown my soul as indicative of his strong belief in ‘upholding indigenous values and national identity over and against external interests’.13 Patrick Flores similarly characterises Bose’s birth city, Baguio, as an enormous influence on his practice, as ‘the wellspring of indigenous resistance’, with its lingering ‘sediments of American colonization’.14

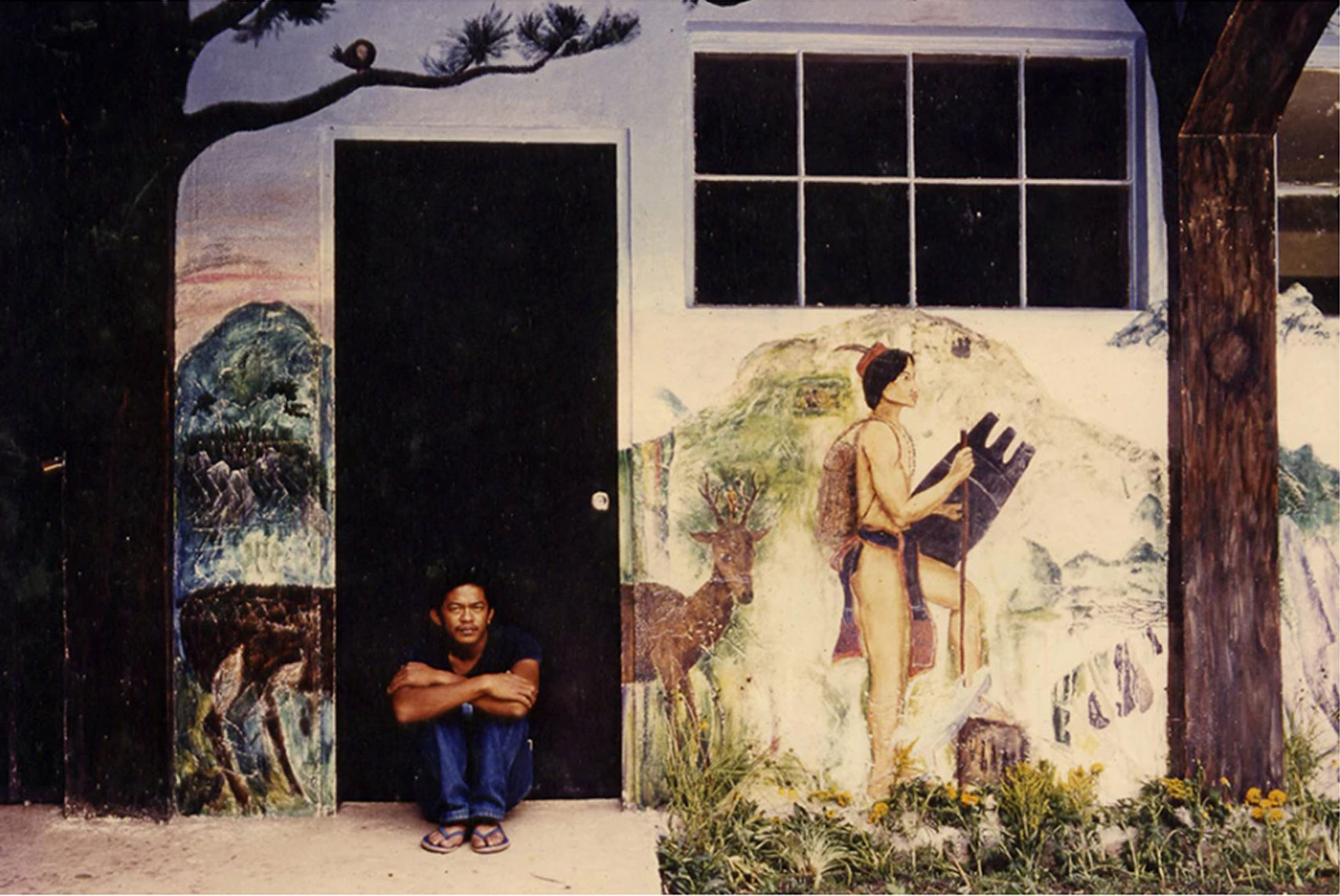

During his time in the Philippines in 1981, Bose spent three months in the town of Sagada in Mountain Province, where he completed a mural over 15 metres (approximately 50 feet) in length and approximately 3 metres (10 feet) in height, on the ground-floor facade of the St Mary’s School quadrangle. Slowly decaying and largely forgotten for many years, the mural was recently restored and reimagined by a group of Bose’s friends and community of artists. Titled Kabilbiligan — which means hillside or mountain in Kankanaey — the mural illustrates Bose’s fascination with the country’s indigenous cultures. It depicts locally recognisable people in customary garments, carved bul-ul (ancestor figures) and the town of Sagada’s rice terraces and famous limestone cliffs. Like Drown my soul, the mural incorporates wood reliefs and, originally, featured collages of photographs and newspaper clippings discussing current affairs embedded in its surface of paint and sculpted concrete.

In the centre of the mural, Bose depicted a bul-ul or carved wooden ancestor figure. To the immediate left, he created a portrait of Macli-ing Dulag, protected by a Kalinga warrior’s shield with its three vertical points. Kabilbiligan was a clear political statement, with its depiction of an impenetrable wall of warriors holding shields. The school’s construction had been recently sponsored by then ambassador Alfonso Yuchengco, a vocal critic of the Marcos government whose son, Boy Yuchengo, commissioned the mural. As Guillermo comments:

The mural stirred controversy among the conservative sectors of the community. This was due to the inclusion of the well-loved pangat Macliing-Dulag who was killed by the military for leading the community’s opposition to the building of the Chico Dam … When the conservatives effaced the portrait, activist youth sneaked in to restore it, this happening several times. Thus the mural became a symbolic site of the intense political struggle that was taking place in the region.15

Following the completion of the mural, Bose returned to the United States. It was not until 1986, with the end of Martial Law, that he once again came to live in Baguio. As is well known, in 1987, Bose founded the Baguio Arts Guild with artists BenCab (Benedict Cabrera), Kidlat Tahimik and Roberto Villanueva. The Guild emerged from an expressed shared desire to strengthen a sense of community and solidarity and to address the rapid modernisation in Baguio that affected the environment and the cultural values passed down by the indigenous peoples in the Cordillera mountains.16 Perhaps coincidentally, the establishment of the Guild coincided with the creation of the Cordillera Autonomous Region, a legacy of the anti-Chico Dam activism of the Kalinga people.

When the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) began in Brisbane in 1993, Filipino artists such as Bose had been practising and advocating for indigenous and grassroots communities at a local and international level for over a decade. The first APT featured Santiago Bose alongside fellow Baguio-based Roberto Villanueva, Nunelucio Alvarado, Imelda Cajipe-Endaya, Brenda Fajardo and Julie Lluch, all of whom made references to vernacular and indigenous customary practices in their works. Retrospectively commenting on the high representation of Filipino artists in that first iteration of the Triennial, artist and academic Pat Hoffie has remarked that one reason for this was that many of them were ‘already grappling with the ideas of cultural imperialism in ways that contested the ideals behind internationalised cultural homogeneity’.17 The works were particularly appealing within an Australian context, at a time when postcolonial theories were beginning to take hold.

In some ways, Bose’s practice resonates with that of Brisbane-based artist Gordon Bennett (1955–2014), whose work is well known to Australian audiences. Emerging as an artist in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Bennett also layered and sampled images in exposing colonial histories and, as an artist, was often categorised as ‘urban Aboriginal’, a label he despised.18 Like Bennett, by the 1990s, Bose had begun to feel uncomfortable about the way his work was tied so closely by critics and the media to discussions of indigeneity. In 1997, Bose wrote of the need for further clarification on the use of the term ‘indigenous’ in relation to contemporary art, and for clearer parameters on engagement with communities and appropriation of cultural expressions. While not disengaging his support and advocacy, he wanted to detach himself from the labels:

The term ‘Philippine indigenous art’ was used by art critics as a convenient name to describe contemporary art practice that is made outside Manila, where artists use local materials and merge contemporary forms with traditional modes. I was reluctant to talk about indigenous art because it institutionalises it. The mere fact that I’m writing about it makes me an accomplice to this naming. Labelling restricts mixing and reduces critical engagement. It also encourages misrepresentation of tribes who are appropriated from. Appropriation by non-tribal groups is not mixing.19

Santiago Bose was one of the first artists to bring indigenous art forms to the fore — the first to ‘indigenise’, to use a Baguio term, a practice continued through different means by many artists and curators in the Cordillera.20 Despite the prominence of indigenous culture in the region, the voices of its artists often go unheard and their works undiscussed beyond the sphere of craft or cultural patrimony. One of the few artists whose work is regarded as ‘contemporary’ is Rocky Cajigan. But before turning to Cajigan, it is important to consider one of the oldest Kalinga artists, whose practice is based on the customary art of batok (tattoo).

Beneath the skin: Whang-od Oggay and Kalinga tattoo

What does it mean to be Filipino? What does art and culture signify? Why do we think almost naturally that art and culture can represent the identity of the Filipino? What is tradition? How do we make sense of it and critically reflect on it? … And what are the stakes in making sure that the life of the art of artisans prevails even amid the adversities of society and the grievous signs of a declining planet?

Patrick Flores, ‘Kaloob: Paghawan ng Landas’ (2020)21

Whang-od Oggay, also known as Fang-od, Whang-ud Oggay, is a mambabatok or tattoo master from the small village of Buscalan, in the town of Tinglayan in Kalinga province. Her village lies along the Chico River and, like Macli-ing Dulag, she belongs to the Butbut people. She is often described as the ‘last’ and oldest mambabatok.22

Batok is a type of hand-tap tattoo that has existed since at least the sixteenth century and was common among warrior groups in the Cordillera, including the Kalinga and Bontoc Igorots.23 Its tools are simple and made from readily available materials. Whang-od begins by tracing a design on the skin with a fine piece of straw; then a gisi (a type of chisel) is made by threading a citrus thorn into a bamboo reed. The thorn is dipped in a mixture of charcoal and water, and the mambabatok then uses a bamboo hammer to tap at the gisi, creating ‘permanent inscriptions embedded in the skin’.24 The intricate tattoos traditionally cover the bearer’s wrists, the backs of the hands, upper and lower arms, the chest, upper back and torso. Smaller cross tattoos are sometimes made on the face. Comparable designs to those used in batok also appear on customary woven clothing, on pottery and on the culture’s distinctive three-pronged shields. Taking the form of geometric patterns and friezes, the inscribed designs refer to elements in nature, from rivers, trees, animals (especially centipedes, snakes and lizards) and celestial objects such as the moon and stars, which provide light and guidance to warriors. As curator and anthropologist Analyn Salvador Amores writes:

Warriors often have special insignias, like the khaman or Kaman (headaxe), to symbolize that the person has participated in headhunting. The bituwon (star), sorag (moon) and the pingao (bird) are expressions which draw from their environment.25

Amores also notes that, on the back of the hands, it is customary for warriors to have a design that represents a centipede eating a lizard. Ufug (centipede scales) and bodies of gayaman (centipedes) are believed to be spiritually charged symbols. The placement of tattoos is also significant; for example, only those who are headhunters have the design that loops across their chests and upper arms.

In recent years, detailed research into the tattoos has highlighted not only their mathematical symmetry and visually powerful symbolism, but also the way they are linked to social status and rites of passage. Tattoos were given at different stages, from childhood to adulthood and into old age. They represent a kind of ‘biographical accumulation’, according to Amores: ‘Kalinga tattoos are deeply ingrained symbols within the specific fields of Kalinga’s sophisticated sphere of social action and different rites of passage in the context of the tattooing tradition’.26 The marks signify belonging to a community rather than expressing individualism, and also communicate milestones achieved — puberty, marriage, childbirth or the number of heads a warrior has hunted in protecting his community. They confer protection from illness and misfortune and allow for recognition in the afterlife. By the 1960s, the outlawing of tattooing and headhunting foreshadowed the breakdown of the context and loss of significance of the art. As with many customary practices, knowledge was often transferred through oral tradition and ‘learning-by-doing’; thus, the intricate patterns and techniques were rarely documented. As the older practitioners have passed away, cultural knowledge has faded and, in many communities, batok has gradually declined.

Given this history, Whang-od Oggay is a rarity, as both a female mambabatok (it was traditionally a male art) and a living practitioner of a disappearing art form. Now over 100 years old, she is something of a celebrity, appearing in books, films, journal articles and in photographs on social media. In 2018, she was awarded the title of Gawad sa Manlilikha ng Bayan (National Living Treasure), bestowed by the Philippine senate, as well as the Dangal ng Haraya (Award for Intangible Cultural Heritage).27 It is not an exaggeration to say that she has single-handedly transformed the village of Buscalan, enabling new housing and livelihoods, and through her example, encouraged younger women to take up the art. She has also become an inspiration for Cordillera artists across diverse mediums, with her face instantly recognisable in many paintings and photographs celebrating indigenous culture.

On the surface, Oggay’s story is one of success. As the NCCA publication announced when she received the awards:

Local and international tourists flock her abode in Buscalan to get inked with traditional Kalinga designs, her signature linear three-dot design, and witness the outstanding whatok techniques which she is actively passing on to the younger Kalingan women.28

But accounts by those who visit her vary. Some are ‘blown away’ by the meaningfulness of getting a tattoo in this remote village from a living legend. Others tell a different story. To keep up with tourist demand, Oggay provides 30 designs to select from, and she spends long days tirelessly tattooing tourists, who line up for eight hours or more. She is concerned about what will happen to her village when she dies; will the younger artists who assist in delivering the 30 patterns still attract the same devotees? In Kalinga society, the tattoos were a symbol of status and achievement. When Oggay first began to practise the art form, as she has explained: ‘I used to tattoo village warriors, and the Kalinga designs meant a great deal to them, but these symbols don’t have the same significance to foreigners who choose more “aesthetically pleasing” designs, no matter the meaning’.29

In 2017, a furore erupted when Oggay was invited to attend the Manila FAME trade show, a showcase for artisans, where she tattooed more than 300 attendees in two days. Although Oggay defended the organisers against the accusation of exploitation, her statement regarding her reasons for travelling is revealing: ‘On social media they were saying that I was exploited but I love what I do and I chose to go and earn money for the village, which has little other income outside of Kalinga tattooing’.30 Oggay’s revered status — acknowledged at a national level and emphasised by the media — has brought adulation far beyond her own community. However, it is also problematic in its implications: the desire for a ‘living, precolonial national subject whose practices authenticate decolonisation and an unconquerable, uncolonised Philippine subjectivity’.31 Oggay’s presence at the fair may have inspired such debate because of a belief that her art should be a ‘pure’ tradition, linked to a specific place and time, and unsullied by commercial profit.32 Yet time has inexorably transformed batok: once a symbol of bravery associated with communal ritual, it was later outlawed and then gradually discredited by its association, in Western culture, with the ‘primitive’ and ‘criminal’; more recently, it has become popular with tourists and young Filipinos as decoration and as a personal rite, rather than a culturally specific practice. While the issues and perceptions around Oggay’s story are complex, they point to a deeper need: to allow transformation and change in indigenous art forms like batok while also supporting artists to ‘persevere and flourish without losing out to the commodity market and the spectacles of identity’.33

Hairlooms and headhunters: Rocky Cajigan

Briefly, I believe in the future development of the Bontoc Igorot for the following reasons … He has courage [and] he is industrious, has a bright mind, and is willing to learn. His institutions — governmental, religious, and social — are not radically opposed to those of modern civilization … but are such, it seems to me, as will quite readily yield to or associate themselves with modern institutions.

Albert Ernest Jenks, The Bontoc Igorot (1905)34

Growing up in Central Bontoc, Mountain Province, in an ethno-linguistic community along the Chico River, is the aesthetic and theoretical backbone of my work. The indigenous cultures of my Ifontok mother and Kankanaey father cross-breeding with an American colonial influence has left me to examine indigeneity, especially my own.

Rocky Cajigan35

Rocky Cajigan works across painting, assemblage and installation. An artist of Kankanaey and Ifontok heritage, Cajigan was born and raised in Bontoc, in Mountain Province. He is now based in La Trinidad just beside Baguio, the largest city in the Cordillera region, in the nearby province of Benguet. In his practice, Cajigan draws on the rich cultures present in the Cordillera region prior to Spanish and American colonisation, to explore aspects of material culture, indigeneity, community, ethnography and museology. He is also a writer, and was a key figure in the restoration of Bose’s Kabilbiligan mural in Sagada.

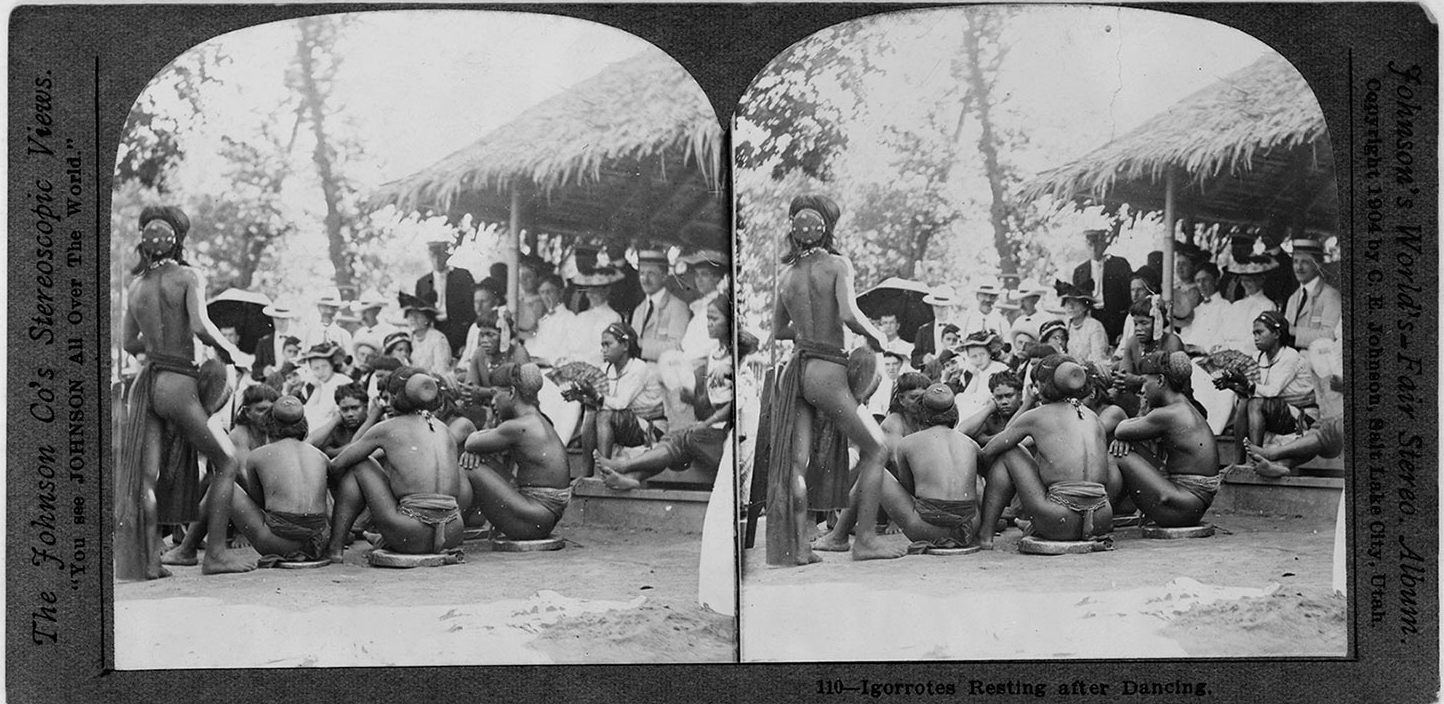

Like the Kalinga, Bontoc Igorots were headhunters, weavers and woodcarvers, and resisted colonisation for many years. Perhaps one of the most infamous examples of colonialism was the transportation of a Bontoc village to the 1904 St Louis World Fair in the United States by American anthropologist Albert Jenks (1869–1953).

Jenks’s photographs and observations on the Bontoc Igorots — made during his two-month expedition to Bontoc and Lepanto — still form one of the major visual and literary accounts of the community. For Cajigan, ethnographic accounts such as these are examples of the painful subjugation of Cordilleran peoples under colonial powers. Jenks mistakenly assumed that the Bontoc Igorots had little culture of their own and would naturally yield to (Western) ‘modern institutions’.36 He had a limited understanding of the complexity of Kalinga culture, its tattoo and weaving traditions and the symbolism behind them, and he disregarded the miraculous rice terraces, since declared UNESCO World Heritage sites.

In creating his works, Cajigan often starts with an object or narrative image that draws attention to colonial histories while simultaneously undermining them. For example, a photograph taken by Jenks of the ancient Kadchog rice terraces in Bontoc formed the point of departure for Cajigan’s Epidermis 2019, in which he explores the importance of place, heritage and adaptation, highlighting the ongoing threat of housing developments to the terraces. More commonly, his works include a profusion of objects calling attention to the material and cultural contexts from which they arose, hinting at prior narratives. Their juxtaposition allows him to build up layered and textured meanings. This fascination with objects also has its roots in his childhood: Cajigan’s mother ran a souvenir shop filled with local and historical items, and his primary school was situated beside the Bontoc Museum, where he was a regular visitor.

Since 2017, Cajigan has created several installations based on the back-strap weaving loom, a device used in communities across South-East Asia, including the Cordillera region. He recalls his extended family weaving customary Bontoc red, black and white garments on these looms, in which the weaver fastens the warp of threads around their own waist. Such textiles continue to have deep ceremonial and social significance, and in general it can be said of Cordilleran culture that ‘textiles permeate all stages of the life cycle, from conception to death’.37 Each garment displays unique motifs and associated symbolism that have developed over centuries, long preceding colonisation. As noted above, they share symbolism of mountains, rivers, animals, and celestial bodies with batok, as practised by Whang-od Oggay.

Cajigan’s site-specific and ephemeral loom works have been installed in locations in Taiwan, Nepal and the Philippines, some using the traditional frame of the loom and others supported by the architecture of the site itself. In each case, the form of the work responded to local histories. For example, in Fabric of Activisms 2 2017, Cajigan used anti-corruption and human rights protest posters as the loom’s fabric, pointing to the association of the University of the Philippines, Diliman (where the work was exhibited), with a history of activism.

The use of red fabric relates to ideas of community and collectivity, as well as to customary weaving techniques. Looped through the remnants of burnt backstrap looms — salvaged from a Bontoc dwelling with burnt household objects — the threads hint at both the destruction and resilience of indigenous culture.

For A Barrier, a Time 2019, in Kaalo Art Space in Nepal, he worked with a Nepalese sukul weaver to create a floor-based lingam surrounded with brightly coloured cotton threads. The work was site-specific, responding to the space of the building, as well as process-based, evolving over time. Each day over a period of three weeks Cajigan added a new thread, traversing the room to create a kind of rainbow maze. Both the woven lingam and the knots used in the maze were informed by discussions with local indigenous artists, and A Barrier, a Time allowed Cajigan to study every corner of the space as a way of coming to terms with ideas of “knowing” and connection. The installation was intended as a visual metaphor for the nature of ephemeral collaborations, as opposed to the transactional connections more common in capitalist societies and in the contemporary art world.

In ‘Collective Memories’, a 2018 exhibition in The Drawing Room, Manila, the centrepiece was Cajigan’s Hairloom 2017 — a large-scale installation of a loom constructed from human hair and wooden loom tools, overlaid on open-weave gauze.

Cajigan collected the hair from salons in the towns of La Trinidad and Bontoc. Through a time-consuming and painstaking process, he and his assistants treated and glued the hair together in larger strands, weaving through coloured threads, until it formed a kind of warp and weft for a reimagined backstrap loom, suspended from the ceiling. As an organic, bodily component, the gathered hair of the work provides a dynamic element that counters the static nature of a museum. It also implies a form of collectivity and communal life characteristic of Igorot culture. With Hairloom, Cajigan literally wove together strands of Bontoc DNA. One aspect of Bontoc culture correctly observed by Albert Jenks was the ili — a communal centre of thatched buildings, which acts as the heart of the village, both physically and metaphorically, reflecting the Bontoc notion of leadership as belonging to a group rather than an individual.

For ‘The 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporay Art’ (APT10), Cajigan is creating a 12-metre loom installation that builds on his initial Hairloom work, incorporating new elements adding to its meaning and complexity. Its weaving stools and supports are made from piedras (sandstone blocks) once used by the Spanish for colonial roads and churches. Garments woven from gauze — the kind used to bandage a wound — are suspended on metal poles, capped with carved wood hands and hung from butcher hooks. A woven shirt, which closely resembles a Cordilleran style of textile, was in fact made in Guatemala.38 This fusion of hybrid objects is characteristic of Cajigan’s practice and creates a strong narrative on indigeneity and cultural fusion, on the wounds to and homogenisation of cultures, but also their ongoing vitality and resilience.

Cajigan came to visual art through a circuitous route, one he notes is common to artists in the Cordillera region. He began working as a project manager for NGOs, inviting artists from outside the community to visit and conduct workshops. While the NGO directors encouraged independence and creativity, they were also constrained by funding and reporting requirements. This was not the case for the AX(iS) Art Project collective, on which Cajigan has worked since 2011. AX(iS) focuses on programming events within the region to expand definitions of contemporary art, inclusivity and access, and independence from institutional modes of display.39 The collective has been instrumental in allowing rurally based and vernacular artists to participate in contemporary art forums and projects.

One project involved the painting of the waiting sheds (similar to bus shelters) along the highway between Baguio and Bontoc. The intention of the project was to reframe these transient spaces as forums for discussion on community issues. The experience of working with up to 150 artists and organising a range of projects was formative for Cajigan. In working for AX(iS), he was exposed to an understanding of how art projects can work as ‘laboratories for collaborations’. In his own experience, these collaborations were already present within indigenous communities. The project also allowed him to better understand his role as a visual artist in the exceptional environment of the Cordillera, where artists naturally take on a parallel role, the ‘overlapping responsibilities’ of a ‘cultural worker’.40 As an indigenous artist himself, and one of the few in the Cordillera who has exhibited outside the region in a contemporary art space, this second role has been particularly significant for Cajigan. If his practice points to the hybridisation and commercialisation of customary cultures, his own role as artist–cultural worker allows a complex point of interface between cultures shaped by different knowledge systems. The combination of these roles indicates a way to both integrate his community and celebrate its uniqueness, as well as navigate the challenges faced at a time in which market forces are superseding an artwork’s original cultural significance, and yet, adaptation is necessary for survival.

The Cordillera region, its history, geography and cultures, have provided a point of intersection enabling this exploration of the varied, yet overlapping, practices of three of its artists. The stories woven here around Whang-od Oggay, Rocky Cajigan and Santiago Bose serve as a kind of microcosm, inviting those outside the Philippines to cultivate a more nuanced understanding of ‘indigenous art’ in this nation of many islands, of the diversity of these voices, and of the necessity to advocate for indigenous works, across media, to be supported, interpreted and exhibited as living and evolving.