Uramat Sivirihtki dance / Photograph: Gideon Kakabin / Image courtesy: Judy Kakabin

Uramat Sivirihtki dance / Photograph: Gideon Kakabin / Image courtesy: Judy KakabinYou can’t know the content of artistic production just by mere display, there is a greater commitment one has to have, art historically and otherwise to be able to pull it off.

Okwui Enwezor1

When you curate an exhibition of contemporary works from Papua New Guinea that employ customary practices, audiences can access little of the community and institutional commitment that goes into building cultural relationships and learning. Yet, for me, this is the most important part.

The Uramat Mugas (Uramat Story Songs) project, in development for ‘The 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT10), is the latest in a number of major projects commissioned by the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) to engage with these practices in an attempt to acknowledge the full breadth of artistic expression across Papua New Guinea today.2

The project — involving Uramat leader Lazarus Eposia and Gunantuna Elder, the late Gideon Kakabin — has been nurtured into being over a seven-year period spanning two APTs, through cultural connections in East New Britain and Australia. The journey has not been without its challenges: the negotiation of the legacy of interactions between the two men’s cultural groups, the involvement of a government-funded Australian art gallery and, shockingly, Kakabin’s sudden death in 2018. As the project continues to evolve, it feels important to share its story.

For Lazarus Eposia, back in East New Britain, the day had begun early. Gideon Kakabin, a former Port Moresby–based IT specialist who had worked with Eposia since returning ‘home’ to East New Britain in 2008, would arrive shortly. On the slow drive up the range to Gaulim village from his own clan land in Nanga Nanga village, Kakabin recognised the patterns he had seen on the masks of Eposia’s people. They were all around him: in the shapes of the leaves on the tall forest trees along the road, and in the snaking line of the vines as they wound their way up into the canopy of the forest — dark tendrils silhouetted against the brightening sky. Eposia was born in Gaulim village. He had tried his hand at growing cocoa and various other jobs around the province, before finally settling into a village administrative position liaising with his people as the teachers’ college bursar and registering a cultural group for his clan — the Indigenous Uramat Identity (IUI).3

Celebrated internationally for their spectacular night and day performances and accompanying masks, the Uramat are one of six linguistic subgroups of the people indigenous to East New Britain, who are incorrectly referred to by the derogatory term ‘Baining’. In their creation story, the Uramat describe themselves as a clan of the indigenous Kate people; the term ‘Baining’ derives from Kuanua, the language of the Uramat’s first colonisers, the Gunantuna (or Tolai) — to whom Kakabin belonged. ‘Bai’ means to go into the bush, while ‘ningning’ means uncultivated area, so ‘Baining’ roughly translates as wild, uncultured people who live in the bush.4

A budding historian driven by a passion for research, Kakabin was aware of the historical forces that had shaped the Uramat’s current situation, including the role that his own people’s occupation of their lands thousands of years earlier had played. Over years of working together and as their friendship strengthened, Eposia had shared with Kakabin the reasons for creating his IUI cultural group, including his frustrations at the continuing lack of autonomy and control his people had in the economic, cultural and political structures of East New Britain. According to Eposia:

Over the years we have been bullied by outsiders who use us to make money. We want the provincial government to recognise that it is our culture. We have been used by middlemen and tourist operators. We, the people, don’t benefit. We are the Indigenous Uramat Identity.5

In July 2016, Eposia needed someone to assist him in documenting the cultural ceremonies being staged to celebrate the 45th anniversary of the Gaulim Teachers College. Driven by a love of culture and a strong sense of justice, Kakabin was compelled to act. The celebrations took place over a week and introduced Kakabin to the variety of Uramat dances and their associated masks. Immersed in the process of documenting these ceremonies — specifically created by and for community — Kakabin developed a greater understanding of the spirituality and the custodial relationship with land that underpins Uramat art.

In October 2016, Kakabin attended the opening of ‘No.1 Neighbour: Art in Papua New Guinea 1966–2016’ at the Queensland Art Gallery (QAG).

The exhibition featured a Bit na Ta (source of the sea) 2016, a multi-art project he had worked on that told the story of the cultural resilience of his Gunantuna people through song and video.6

Towering Uramat madaska day masks were on display alongside kavat night masks, and Kakabin generously spent time with the curators correcting texts and expanding understandings of Uramat culture, based on his recent experience documenting Gaulim ceremonies.

A return visit to QAG at the end of 2016 to explore photogrammetry techniques for 3D scanning of sculptural objects prompted Kakabin to think about the ways in which these digital technologies could both preserve cultural knowledge within community and engage outside audiences in the continuing vibrancy of ceremony. He was excited about the potential for local cultural groups to achieve these ends without having to invest in expensive and culturally alien museum infrastructure that was difficult to maintain, and which could be co-opted by political forces driven by the tourism board or neighbouring clans.7 He thought of Eposia, and it was this idea that brought him up the mountain to Gaulim village.

I can see Kakabin sitting in the cab of his red Toyota Landcruiser, dusty from the journey up from Nanga Nanga, at ease waiting for his friend. As Eposia emerges from a dark blue cinder-block building, Kakabin climbs slowly down from the cab — then leans back in to retrieve two loosely tied bundles of fresh, local peanuts. Handing one to Eposia, he keeps the other, cracking the shells with surprising dexterity and speed for a man with such big hands, popping nuts into his mouth like a kid with a bag of lollies. There is a relaxed exchange of greetings, before the two men skilfully devour the nuts, dropping the shells to the ground. Only after they settle back into a familiar rhythm does Kakabin approach his friend with his idea.

From Eposia’s descriptions, Kakabin showed him the photographs that he had taken in Brisbane, telling him about the innovative projects he’d been working on and proposing to introduce Eposia to his contacts at QAGOMA. Kakabin suggested they begin by creating a collection of ceremonial masks, possibly to be documented via photogrammetry, that would be stored by the Gallery, who would act as custodian, or lukout papa. According to Eposia:

We want to put everything somewhere, so in the future when our youth have lost our culture and technology comes up, we can retrieve it. This year alone we cannot do the fire dance because youths of today are involved in drugs, alcohol and problems with law and order. If kids go into these activities, we lose our culture.8

Like the Uramat, the Gunantuna had also faced the prospect of cultural change and loss. One of the messages Kakabin had hoped to convey with a Bit na Ta (source of the sea) 2016 was how significant the retention of traditional Gunantuna cultural values and practices had been to the group’s ability to successfully navigate change. Bringing together archival footage and the infectious rhythms of popular Gunantuna string bands, a Bit na Ta drew younger audiences to witness how — leading up to Independence in 1975 — the Gunantuna had mobilised their own strong relational economy to counteract the control of the colonial Australian government.9

Kakabin proposed that Eposia and his people work with curators at QAGOMA to not only create a safekeeping place for their masks and the knowledge they embodied, but to develop a dynamic new project that would contextualise the masks, their ceremonies and related stories. This immersive audiovisual project would be led by the Indigenous Uramat Identity group to be presented as part of QAGOMA’s APT10. The project would also honour the music of the Uramat by involving a collaboration with Australian music producer David Bridie, who had worked on a Bit na Ta.

As these discussions played out between late 2016 and early 2018, Kakabin and his son Tipia travelled regularly up the mountain to their land near Gaulim. With assistance from Eposia, they identified an intergenerational group of Uramat men who agreed to be interviewed as they created more than 70 day and night ceremony masks. Visiting the men in their village homes, sharing food and walking with them through the forest to identify plants and materials, Kakabin had a privileged window into their world. His involvement in the men’s personal stories afforded him an understanding of the epic foundation of their beliefs, which centred around a parallel universe: a replica of the physical world where every individual has a spiritual counterpart who is both a protector and avenger — and whom one must keep appeased.

Drawing on his IT skills, Kakabin worked with Eposia and the men to develop a new database for the masks that contained both technical information and significant stories related to the objects and ceremonies.10 Created for use by both the community and the Gallery, the database details the place of origin, as well as the tribe, clan and family to whom each mask belongs, in addition to the purpose, title and creator. A young Uramat painter, Nerius Toule, was commissioned to paint a mural on a 44-foot shipping container, which transported the gifted works to QAGOMA, where they were welcomed in song by members of the East New Britain community and First Nations staff in April 2018.

According to Kakabin, after two years of negotiations, packing the masks into this spectacular steel vault was an emotional milestone for all involved:

Over many generations, the Uramat artists are the reasons why these spirits and dance objects have survived the ravages of time and cultural and religious turmoil. It is therefore critical that their permission is sought in a project of this nature. All the artists freely agreed to participate in this project although it took time before they would all agree. They needed to understand the importance of their work which to them is sometimes ‘only’ play and relaxation time.11

Kakabin recorded his conversations with the artists regarding the reasons for creating the project:

Lazarus and I have been working on a project to help you showcase your masks and if the mask is in Australia, visitors coming to the museum will see the mask and if they are interested, they will come to your place to see the real dance. Do not think that all of us will become millionaires, no. This is not our aim. We will make a little bit of money … and, in the end, preserve the stories.12

Kakabin travelled to Australia in the middle of 2018 to undertake a residency at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, stopping in Brisbane to see the masks settled in their new home. A few months later, as he was preparing to return home via Brisbane to discuss the masks’ presentation, he passed away. His death very quickly revealed the dynamic part he had played in the project: in the masks and ceremonies of the Uramat, Kakabin saw not only aesthetic sophistication and a complex culture, but an opportunity to follow his dreams of recording history from an indigenous perspective. He wanted to remove the layers of privilege and bureaucracy that separated the Uramat and Gunantuna — and which kept one people subjugated to the other — by establishing instead a relationship of reciprocity and respect.

In agreeing to the collaboration, Eposia and the Uramat artists played an equally significant role. The Uramat — cognisant of the opportunities that the Gunantuna had historically been able turn to their advantage — maintained a long history of resisting outside engagement with their culture. Over time, Kakabin demonstrated his commitment to the Uramat worldview. Where others came and went, driven by the tourist dollar, Kakabin immersed himself and his family in Uramat stories and ways of thinking. With the project’s main advocate gone, how would the project proceed?

I first met Eposia on a trip to East New Britain in 2017.13 With Kakabin unavailable, the meeting was hosted by his clan brother, Tiolam Wawage, and Tolai representatives from the Provincial Tourism Board. A man of few words and big silences, Eposia was reticent; it was not until my third trip to Gaulim — accompanied by Judy Kakabin (Gideon Kakabin’s wife) in July 2019 — that this reticence began to ease.

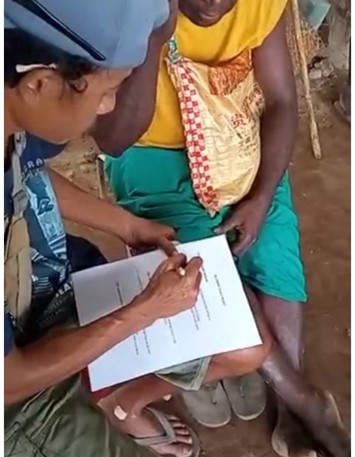

I remember sitting in blue and white plastic chairs in the sparsely furnished room that Eposia had organised at the teachers’ college for our stay. Leaning on the table, Eposia presented a neatly typed document that he had prepared outlining the infrastructure that his community required to realise their aspiration of creating their own cultural centre. The way Lazarus told it, the money that the community received in return for the dances that they had presented in the past was a pittance: just two and a half per cent of event takings. ‘We have this problem’, he softly said, ‘with the Tolai, and we want to do this ourselves’.14

I apologised to Eposia, explaining that QAGOMA was not in a position to buy a truck or build a cultural centre. The best we could do was to pay a commissioning fee directly to the clan, as well as cover the production costs of the project if we created it together. Importantly, they would direct and own their work, allowing them to sell iterations to different institutions. I also revealed that the Gallery would apply to the Australian Government for funding to bring 15 community members to Brisbane to share their story directly with audiences to make the most of the exposure that APT10 would provide.15

Although this was not the outcome Eposia had wished for, he thoughtfully weighed his options. There were no avenues for cultural funding in East New Britain or even nationally in Papua New Guinea. He had chosen to work with Kakabin and the experience had been deeply rewarding. Young Uramat men had blossomed learning how to document the masks, and then preparing and packing them for safe shipping to Australia. There would be more opportunities for learning when the audiovisual team, employed to document the ceremonies, travelled to the village to record sound and video. The proposed trip to Australia would generate even more connections.

Eposia then went on to outline numerous conditions, the first of which was that there would be no iconic night fire dance, or Engini, performed outside of its indigenous home. Some Engini are short — over in a couple of hours — while others start soon after sunset and continue until dawn, with only a few short breaks to relieve the members of the bamboo orchestra. All Engini are performed in a circular clearing, at the centre of which a large hungry fire is constantly fed by a group of older men. In the ceremonies I have attended, individual masked figures come to the fire, one by one, dancing by stamping and twisting their feet to the pulsating rhythm established by the orchestra and a chorus of male singers. The intense drama of the event slowly builds as the crowd of spirits grows and the music picks up speed, sending one or more dancers, sparks flying, into the fire.

Engini are customarily associated with the initiation of young men or the marking of key rites of passage, such as birth and death, but over the decades, they have increasingly been staged to mark other significant milestones. Since the 1950s, when the first cultural ‘shows’ and ‘festivals’ were initiated in the New Guinea Highlands by Australian colonial authorities, there has been a steady increase in demand for customary forms of art at these events. In East New Britain, the fire dance has become one of the most popular features of the Gunantuna-led National Mask and Warwagira Festival, and a recommended ‘cultural experience’ for tourist groups visiting the province. Esposia recalls that tourist operators were already visiting his village to view Engini when he was growing up in the 1980s.16

In response to concerns of commercialisation, different clan groups have formed associations, like Eposia’s Indigenous Uramat Identity, aimed at protecting culture, land and ritual. For instance, in 1991, clan leaders challenged decisions by the East New Britain Tourist Board to send ‘fire dancers’ to the Pacific Games and to a trade exposition in Japan, arguing that the pressure to ‘perform’ showed a ‘disrespect and total disregard for the rights and the identity of the Baining and their culture’.17 Recently, various groups have actively sought to remove their cultural materials from public contexts if they feel that there is a threat of exposure of cultural secrets or a misuse of attendant images.18 Furthermore, after a number of instances where audience members have interfered with the Engini — throwing bottles into the fire, and adding harder and ‘hotter’ wood — the majority of clans have decided that fire dances will not be performed in East New Britain towns or for the National Mask Festival.

While the Uramat would not be staging an Engini in Brisbane as part of APT10, the distinctive masks created for it are integral to the story that the clan wanted to share. It was Eposia who could guide the presentation of the masks without breaking important cultural protocols. Although he was able to travel to Brisbane in early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent hard border closures scuttled further trips. Working remotely, Eposia articulated the importance of communicating ideas of restricted access, while ensuring that audiences could still experience an inspired appreciation and understanding of Uramat culture and beliefs.

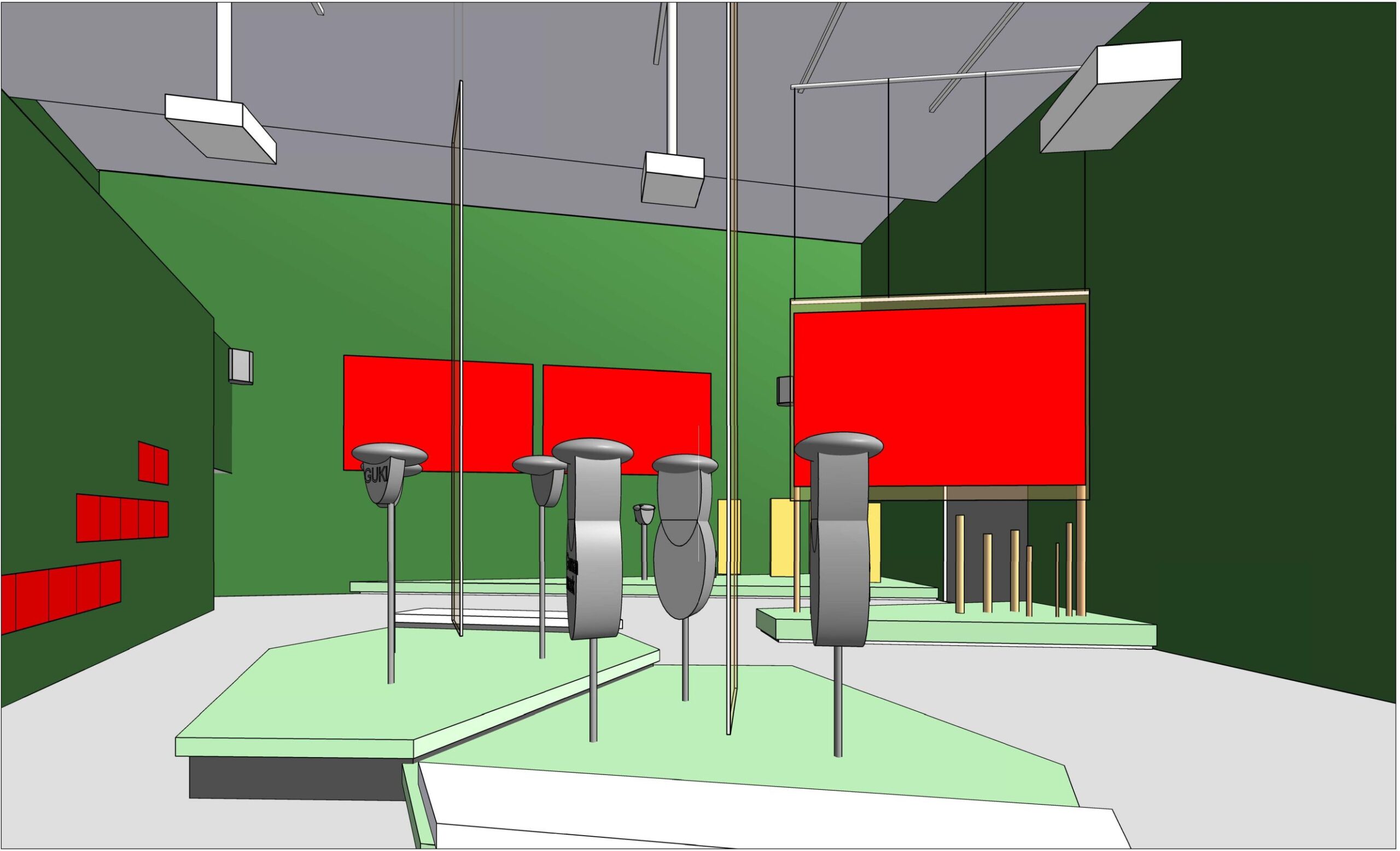

With these parameters in place for the APT10 exhibition in Queensland, the project’s Australian team — which had grown to include new media artist Keith Armstrong and Queensland University of Technology (QUT) producer and lecturer Joanne Kenny — envisaged a space that responded to the mystery of the Engini ceremony by keeping the masks as required by Uramat protocols, embodied by dancers and safely shielded from view through layers of light and imagery.19 A projected video recording of a special ceremony, hosted by the IUI, would provide these layers of concealment, as well as the context to bring the scene alive. Reinforcing the project’s title Uramat Mugas (Uramat Story Songs), music would play an important role in transporting audiences to ‘ples’ (place). Eposia’s reaction to the team’s proposal was positive: ‘You have been listening’, he said. ‘I love this.’20

The ceremony at which sound and video would be recorded was scheduled for 3 December 2020. As Eposia worked tirelessly with community to prepare for the event, a local audiovisual team was contracted, with Eposia’s and the community’s agreement. The team — Juan Low, Garett Low and Ian Boas — came together in Gaulim, and messages began to flow excitedly between the village and Australia. On the ground, the local team worked closely with community by recording interviews, and documenting cooking and weaving demonstrations, as well as drawing workshops with the children. Then, on the night of the planned Engini just as the fire was being prepared, the village court issued an order banning the event. This shock came at the instigation of a member of the Qaqet Stewardship Council, which was created in the 1980s to protect culture from exploitation. The order was, on inspection, an amendment to an earlier claim against a local man who had sold a mask to a man from the New Guinea Highlands. Eposia’s name had been added, months later, as a person the claimant argued was showcasing sacred cultural assets to tourists for monetary gain.

Asked how this could have happened, Eposia explained: ‘There are a few people in the village who are jealous. They don’t understand what we are doing and spread false information that this ceremony was for tourists’.21 Speaking with Eposia on the day of the scheduled legal hearing, he was adamant that he and his team had complied with the Council’s rules:

You have seen the program for the filming. It is all about education and preservation. It is okay, the project can go ahead. We are following the rules. This is good for the Uramat.22

Judy Kakabin concurred, explaining that the forests where the clan sources the bark for their masks were under threat from logging and palm oil farming, and that Eposia’s project helped the Uramat to document and preserve their culture. ‘This is important for the Uramat. Lazu is an honest man’, she said.23

Village courts operate independently of the formal legal system in Papua New Guinea. Overseen by local magistrates well acquainted with the customary practices of the community, village court’s focus is to ensure harmony within the communities in which they operate. In cases like the one involving Eposia, where ownership of Engini does not lie with an individual but is held communally, the emphasis is less on the two parties involved and more on finding a solution that abides by cultural protocols and law.24

At play in this case is a problematic history of interactions with outsiders, and different levels of exposure to contemporary art museums and the ways the institutions work with indigenous knowledge holders. As a result, there are very different views on the degrees of engagement with outsiders that are deemed necessary to maintain the cultural integrity and the secrecy of the ceremonies and beliefs involved.

As is common with village court proceedings, the case is still waiting to be heard. Eposia attended the scheduled hearing in December; however, the claimant failed to show and the hearing was deferred. As we await the result and continue to work with Eposia and the community, it is worth revisiting Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor’s thinking regarding the necessity to understand local art historical contexts in the presentation of work from other cultures. According to Enwezor:

I think that at the same time there is a kind of romanticism that people have that there will always be a misunderstanding when you take on the work of other cultures. These do happen, but those misunderstandings can never be addressed unless you make an attempt.25

Uramat Mugas (Uramat Story Songs) is that attempt at understanding.