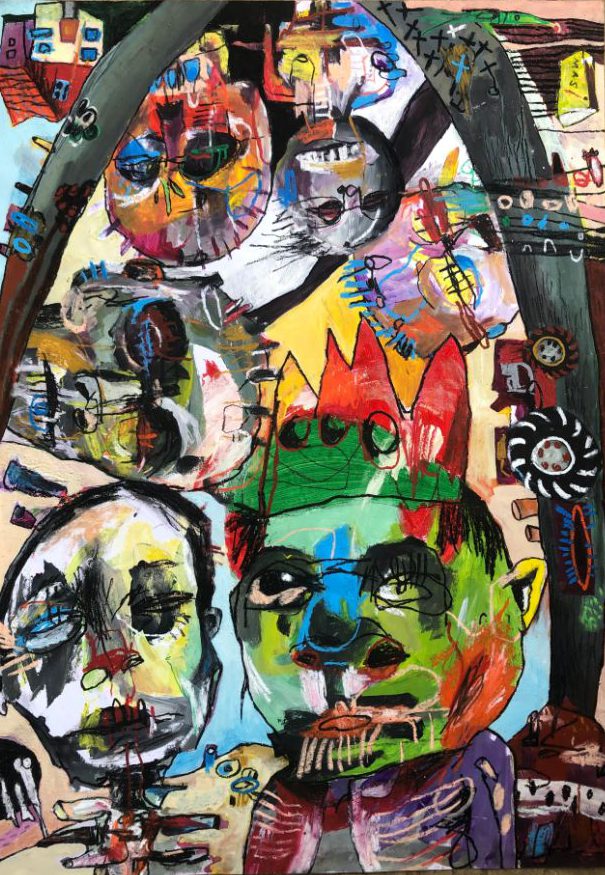

Taniela Petelo / NCD 2018 / Mixed media / Dimensions unknown / Image courtesy: Taniela Petelo / Photograph: Taniela Petelo

Taniela Petelo / NCD 2018 / Mixed media / Dimensions unknown / Image courtesy: Taniela Petelo / Photograph: Taniela PeteloIn the modern world art is considered an individual’s affair. We, however, view art from the interest of a collective and encourage our artists to nurture each other. We do not spurn individualism; we choose to give priority to the collective.

Epeli Hau’ofa, ‘Our place within: Foundations for a creative Oceania’ (2008)1

This short statement from the late Epeli Hau’ofa, renowned artist and scholar, refers to the creative communities of the Pacific. As I reflect on the actions and attitudes that have shaped the emergence of the Seleka International Art Society Initiative (Seleka), I see a living example of Hau’ofa’s words. Seleka is an intrepid artist collective learning to cultivate reflective creativity and demonstrating the power of an unconstrained imagination within the unique context of the island Kingdom of Tonga. The ethos of their practice honours and accentuates the inseparable link that exists between the production of their works, which have a distinct aesthetic, and the creation of spaces that promote creative cultural production. This essay offers some reflections on the significance and particularity of Seleka’s approach to the latter. It draws heavily on insights gleaned from recent conversations with the two lead artists of the initiative: Tevita Latu and Taniela Petelo.

For Tongan-born artist and founder of Seleka, Tevita Latu, the decision to return to his homeland after completing a bachelor’s degree in Fine Arts from the National Art School in Sydney is noteworthy in itself. The opportunity to attend university overseas is not available to many Tongan nationals. For those who do have this opportunity, it is most commonly pursued with the aim of becoming managers, bureaucrats, business entrepreneurs or academics, often with the preference to secure employment abroad. For Tevita, the motivation to attend university was to be able to live a life dedicated to making and teaching art back in his homeland.

Tevita’s deep conviction in the value of visual arts practices that extend beyond the use of local materials and methodologies emerged at a young age. Captivated first by the storytelling power of comic books, and later by the resonant Pacific spirit he sensed in the colour, lines and textures of works by Pablo Picasso, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Egon Schiele. Tevita’s interest in art quickly grew through daily practice and consistent family support. He has expressed that access to a Western arts education, with its experimental approach to using new methods and materials, had a transformative impact on his life. Learning art making from an expanded variety of sources allowed him to ‘accumulate new patterns of thinking, new ways of seeing things’, and to build capacity for self-reflection and expression.2 This exposure consolidated his conviction that access to an arts education is ‘just as relevant as teaching science [or] geography to young people. It’s applicable. It’s necessary — just as necessary, just as needed’.3 And so, upon completing his degree, Tevita returned to Tonga with the intention of creating opportunities for others, particularly youth, to experience and experiment with art unbound by social norms. His vision was that this would ultimately enrich both the lives of the participants and those in the wider community. Despite initially taking up employment as a tertiary art lecturer, Tevita was intent on exploring ways to achieve this vision beyond the confines of formal institutions. A pivotal shift occurred when he began to focus on working in his own village, Haveluloto.

Seleka was founded in 2008 with the integral support of one of Tevita’s earliest art students and later collaborator — his neighbour, Taniela Petelo. Taniela had left tertiary education to care for his parents, but his self-driven interest in music and art motivated him to continue to spend much of his spare time drawing and making music. He soon fell into a routine of regularly attending the local kava club,4 Kalapu Talakeiola. Every village in Tonga has at least one kava club, usually based in a small hall, where men gather most nights to drink this earthy beverage, share stories, exchange jokes, discuss current affairs and sing together. To attend the space, it is typically expected that one contributes either financially or musically. As a talented musician, it was not unusual for Taniela to attend every night of the week, except Sunday.5

Tevita’s family home is located directly across the road from Talakeiola, on the edge of the Faga’uta Lagoon. Despite its convenient location, Tevita usually preferred to spend his evenings painting in his hati6 at home or drinking kava with a smaller group of friends. On one of the rare occasions that he attended Talakeiola, he was seated next to Taniela and introductions quickly led to the discovery of their common interest in art. Taniela began to escape his singing duties at the kava club to join Tevita and a friend named Peni Fagufagu by the lagoon, where they would share kava out of a cooking pot instead of the traditional wooden bowl, and listen to their own music from the stereo connected to an extension cord from Tevita’s home. With their ongoing conversations feeding and inspiring their art interests, Taniela began to regularly join Tevita at his hati to paint. In time, Taniela’s commitment grew to be a daily practice and Tevita supported him to work towards an exhibition of his work at a local cafe. Taniela reflects that at the beginning of Seleka’s formation, it was a similar story for many of those who started to visit the hati regularly. At first, there was an attraction to a new space to hang out with peers, listen to new music, drink kava and participate in interesting and humorous conversation. Newcomers were also able to observe people making and talking about different kinds of art and gradually they would find themselves encouraged to help out in some way, contribute to an artwork, start their own, or test an idea. A growing number of youths from the village started to fall into this new pattern of night activity, prompting the need for a larger gathering space.

My family and I were living in the same village at the time, and I remember visiting the first studio space Tevita and his peers built there for their growing group — a small, coconut-thatched fale (house) overlooking the expanse of water. The space seemed to have spawned from the kava club next door. In a similar way, it was a gathering place where a communal kava bowl (or pot) was central, but so were communal art materials — acrylic paints, paintbrushes, paper, recycled plastics and dyes. There was also a growing collection of books about Western artists and art theories, and a stereo playing music from unfamiliar genres and musicians scarcely heard on local radio stations (including opera, classical, dubstep, house, techno, trance, rock and world music). Every surface of the fale gradually became covered in coloured paint and painted or recycled objects. Unlike the kava club, there was no expectation to contribute financially to attend this space.

With Tevita’s and Taniela’s consistency and generosity of time and knowledge, the conditions in place discovered and nurtured a growing number of aspiring painters, sculptors, musicians and dancers. The majority of the visitors were local youths, but the studio quickly came to be known as somewhere where anyone was welcome. Those who did attend were expected to abide by rules such as no bullying or judging others. Tevita lives by the belief that ‘you cannot be a good artist and yet have a distasteful personality; your personality will far be remembered than the work you get done in this world’.7 The emphasis on character building also found its way into their methods of art making. For example, Seleka artists rework rather than discard any artwork to promote discipline and perseverance. An awareness of the preciousness of life and value of spending time productively is also promoted. Taniela and Tevita continued to paint at the studio every night, but the commitment they had to refining their own practice was inseparable, even secondary, to their commitment to providing the space for others to learn, experience and experiment with art firsthand. And so, the daily rhythm gave way to a steady and empowering release of creativity. Relationships of mutual respect and encouragement were forged and the evolution of a unique kind of arts collective took root.

In this environment, which mirrors familiar approaches to relationship building and social interaction in Tonga, this growing group of young creatives had the unique opportunity to identify and hone their artistic skills. In the years that followed, the collective has been offered both paid and unpaid painting jobs in their own village and across the island, decorating shop fronts, taxi stands, government signs, banners, and derelict buildings or ‘empty walls’. In one project, Seleka painted 30 green bins in support of an anti-littering campaign. Opportunities to collaborate with other local and international artists and youth organisations have also arisen. Some community members offered support in accessing and managing small grants related to youth employment and skills development. Within a few years of building the studio, Seleka started to run art workshops for younger members of the community and would often offer face painting at different community events which, to the great interest of local residents, frequently turned into more elaborate body and clothing painting sessions for the team. As they experiment with collaborative artworks and support their more confident artists to produce solo work, Seleka continues to explore creative ways to exhibit and present their work in a local context. It has become known for setting up unconventional pop-up exhibitions alongside major cultural events, such as agricultural shows and national festivals; creating both permanent and temporary art installations and performances in public places; working with local, private and public businesses to exhibit art; and pricing work to allow a broad cross-section of the community the ability to purchase Seleka art.

Members of Seleka are called Selekarians. Tevita explains that anyone can be a Selekarian. Basically, if you spend time in their studio space and are happy to be given a Selekarian nickname and to put up with the name and title, you can be a member. He elaborates, ‘the title could just be a name to put on your shoulder … some people want to hang out, they would paint, make music, make videos or just drink kava, some people just like the name, alone’.8 The focus of the group is what it can offer its members rather than the other way around. The flexibility and openness of the membership structure and of the space have led to a dynamic arts ecology where teams dedicated to pursuing different artforms — dance, drama, filmmaking, music, poetry, and various forms of visual arts — organically form, shift and cross-pollinate, enriching and diversifying the group’s outcomes and community engagement.

The open-door policy also welcomes the perspectives, engagement, and support of international visitors and creatives. Seleka has developed strong networks with artists and academics across the Pacific. Even New Zealand actor Sam Neill visited the studio during his short trip to Tonga and agreed to receive a nickname and become a member of the collective. When the Seleka studio was devastated by Cyclone Gita in 2018, a group of New Zealand-based Tongan artists responded immediately by fundraising for the rebuilding of the Seleka studio space.

In early 2020, Tevita’s family generously offered the garage and laundry space of their home to be transformed into the group’s new studio. The design of the new larger space became a collaborative art project in itself, and it is made almost entirely from found, recycled and repurposed materials. It took about three months to build and was completed in June 2020. From the outside, the studio resembles a traditional Tongan fale: it is built from local timber; woven coconut leaves thatch the roof and form the walls; and the structure is surrounded by neatly arranged tropical pot plants. However, inside, it is unlike any other room in the country — a space designed to flaunt the power of the imagination, and resourceful collaboration. Every view of the room is tempered by creative flair. The ceiling is completely covered in painted recycled objects, including plastic bottles, shoes, cushions, bark cloth and bamboo. The walls are brightly coloured and feature more elaborate sculptures and wall hangings, also made out of found, gifted and recycled items (e.g. an old violin, a painted cow skull, a toilet seat). Neatly arranged books and art materials fill a collection of bookshelves, including those built into a repurposed fridge. The rubbish bins are covered in children’s recycled toys and an eclectic collection of tables, chairs and couches fill the spaces between.

With this new space, Seleka has been able to expand the scope of their work. In early 2020, they started a formal residency program available to youths from the outer villages, islands and overseas. They continue to thoughtfully engage with various government and social action initiatives, addressing issues such as climate change and environmental health; promoting agriculture; and raising awareness about non-communicable diseases, addiction, road safety, voter education and youth violence.

The developments I have thus described did not come about without numerous and ongoing challenges. Seleka has persevered along an unmarked, and at times controversial, path. Although they have garnered strong support and appreciation from creative communities outside of Tonga and the international community living in Tonga, the freedoms they promote have, at times, been viewed as contradictory and destructive to local religious and cultural standards and norms. Misconceptions about their intentions have dissipated over the years as the vision and boundaries of the group have gained clarity and the commitment of the growing core team has gained strength. In turn, they have achieved greater reach with their work and have been able to weave their activities more deeply into the life of society.

An area in which they are making increasingly significant contributions is that of education. This is by no accident. As Tevita states:

I believe I am living the dream that I dreamt once, it was just to be back home, and teach and help and that’s what I am doing. I guess that is what makes me happy. I would drop everything … For this reason only, I would leave art to go teach art and do so happily. It has been a long passion.9

In order to broaden the reach of their efforts and to impact a wider cross-section of their community, Seleka has taken on the challenge of extending the experience of the studio space to embrace other diverse settings. The effectiveness of this flexible approach is gaining local and widespread recognition. In 2020, the initiative was invited to run regular art classes at Tonga High School, the country’s leading government secondary school. With a focus on teaching art and enhancing the institution’s capacity to foster creativity, Seleka was given permission to involve the students in repainting the walls of many of the school’s main corridors and communal spaces during their art workshops. This resulted in a major transformation of the school’s facade. But even in art classes where they don’t have the time to make such drastic visual adjustments to the environment, Seleka endeavours to find other ways to shape the space in order to enhance creative capacity.

Particularly noteworthy are the workshops they have been delivering for primary school students in the outer islands. My more recent conversations with Tevita and Taniela coincided with their travels through two of the main island groups — Vava’u and Ha’apai — with seven other members of Seleka (Poli Tau’alupe, Lasike Tupou, Paula Misa, Sione Latu, Yasmin ‘Ahohako, Casey Vea, and Mike Tonga). It is clear that much thought is given to the way that these workshops are designed, with their explicit purpose to engage students in a process of self-reflection, critical thinking, and the building of courage and confidence to express their thoughts and to think creatively about the world they live in.

In all locations, Seleka offered workshops for up to 30–50 children at a time over three to four days, supplying them with paint, brushes and paper. The participants ranged in age from eight to sixteen years old, and Tevita and Taniela noted that this was the first opportunity most participants had had to paint or hold a paintbrush. Each workshop built on the previous one(s), running for five or six hours, interspersed with dance and movement sessions. The students advanced their understanding of the basics of colour — how to mix colours, the attributes of warm and cool tones, how to recognise the properties of light and dark shades, and how to play with composition — as tools to illustrate their thoughts, feelings and ideas. During one conversation I had with Tevita and Taniela, they reflected on observable transformations in the students and the elements they feel are critical to achieving this. Tevita shared:

We go in there, we show them gratitude, we show them love and respect. First of all, they must see that in you, they must receive that from you. First thing. And then we teach them at the same time. And in your style of teaching, you make it that you are concerned and care about what you are sharing. You give it your all. If there are concerns or questions, you invest your time in that … I just believe in this. When they feel they are respected and loved, they open themselves up easily, we can talk with them, converse with them and it’s so much easier for them to share what is in their minds … We hand out the material and we just say go on, go forth and just paint what you like. We just stay behind them and let them take the lead … We let the kids teach themselves, but we are just here to assist them. We provide them the paint, so they paint. In fact, we are really guiding them.10

In the Seleka workshop space, there is a deliberate decision to only speak Tongan and to play a variety of unfamiliar music during the classes. The work is not graded and the Selekarians emphasise through word and deed that they are also there to learn from the participants; as Tevita asserts, ‘They teach us a lot too, it’s a give and take in that classroom’.11 The students work in small groups with the full attention of a Selekarian. Each student is offered individual attention, and Tevita will make sure to speak with every student in the room himself to explore the strengths and further possibilities of their work. There are no mistakes in the class and students quickly learn that it is not an option to ‘get another paper’; instead, they learn to problem solve as the creative process unfolds. Over the course of the workshop, students steadily build confidence to not only ask questions and experiment with bolder ideas, colours and shapes, but also to talk about their ideas, reflect and refine their work, and integrate constructive feedback. In doing so, the students are encouraged to engage freely in conversations about the way they see the world around them, avoid the tendency to compete or look to others for approval, and remain eager to strive for excellence in their work. Even when responding to opportunities to engage with international audiences, Seleka strives to ensure that the collaborative art-making approach, which transcends the boundaries between teaching and learning, continues to be consciously infused into their creative processes.

Regardless of whether the rich art experiences offered by Seleka are being provided daily, as in their studio space, or irregularly, as with their travels to the outer islands, Seleka’s objectives are the same — namely, to create spaces and shape environments that effectively stimulate and enable creative cultural production. Seleka continues to learn about how to achieve this vision in ways that are directly responsive to the needs of their community. Their vision is informed by an intimate understanding of their society, and a deep love and respect for the people they work with. In his essay, ‘Our place within’, Hau’ofa presents the following reflection as a universal truth: ‘in order to be continuously creative, we must have spaces where we give free rein to our imagination and ample time to experiment with and develop new forms and styles that are unmistakable ours’.12 In this context, it is clear that the skills and insights Seleka have generated, tested, and refined over the years have much to offer the world. The adaptability, resilience and vibrancy of the world’s cultural biodiversity is safeguarded by and dependent upon thriving cultural arts practices. Within today’s globalised world, the importance of creating environments where artforms are enabled to flourish and evolve at the local level is paramount. This work relies on a kind of creativity that is responsive to changing social environments and is firmly rooted in the continuous historical narrative of our distinct societies. The trajectory of Seleka’s evolution over the last 13 years and their dedication and commitment to a comprehensive arts practice testify to the role they play as essential contributors to the cultural biodiversity and creative health of their society.