Montien Boonma / Thailand 1953–2000 / Lotus sound 1992 / Terracotta, gilded wood / 390 x 542 x 117cm (irreg.) / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 1993 with funds from The Myer Foundation and Michael Sidney Myer through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © QAGOMA

Montien Boonma / Thailand 1953–2000 / Lotus sound 1992 / Terracotta, gilded wood / 390 x 542 x 117cm (irreg.) / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 1993 with funds from The Myer Foundation and Michael Sidney Myer through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © QAGOMAIn acknowledgment of the 10th iteration of the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT), QAG’s former director Doug Hall AM reflects on the challenging circumstances that led to this groundbreaking exhibition series that has gained an international reputation.

The circumstances of how and why ‘The 1st Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT1) was conceived, developed and realised is an account that is not simply about a cultural project. It is not possible to consider the APT without understanding the historical and unique circumstances of the Queensland Art Gallery that created it. Further, it is not a mirror of any other history you might find in Australia’s major public-funded state and national institutions.

It is a story interwoven with politics and rejuvenation. It is important to discuss this because nothing like it happened elsewhere. And it is not vainglory, but a description of a peculiar and localised history, where nothing sat as mutually exclusive from anything else.

It is important to know something of the Gallery at the time, and the broader cultural and political circumstances, to give a clear picture of why the APT seemed like a good idea. But one thing needs to be made clear at the outset: the APT was a concept born out of the Gallery’s own situation. Various interests supported it, after they were inducted into what we wanted to do. It was not an inspired program of state cultural diplomacy, even though politicians on all sides were happy to promote it as such.

The scene was set with my arrival at the Gallery, where I ended up being Director for the next 20 years. When I went for an interview for the position in the second half of 1986, I had never visited Brisbane before. This was the time when longstanding Premier of Queensland, Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s Nationals were in extreme conflict with their coalition party, the Liberals. The Nationals and Liberals despised each other and certainly more than their instinctive nemesis, the Labor Party. Despite Joh firmly holding the reins of office from 1968 to 1987, thus becoming the longest-serving premier in Queensland’s history, at this point of my arrival, his government was very distracted.

In 1987 I arrived in Brisbane with various briefings piled on my desk. Among them was a note concerning a visit a recent minister had made to the Gallery in 1986. Peter Richard McKechnie was a lay preacher and farmer. He arrived at the Gallery with his political advisor and paced the length of the Gallery’s walls, and notes were taken. He quickly formed a view of the lineal hanging space that was given to art that was unacceptable — mainly contemporary art. Seemingly the die had been long-cast. That the political winner takes all — albeit thanks to gerrymandered seats which allowed 26 per cent of the vote to maintain power — knew no bounds.

On New Year’s Day 1987, Joh Bjelke-Petersen announced he was going to Canberra, and that he would be the next prime minister. Among a mishmash of policy gibberish was a 25 per cent flat tax and the withdrawal of Aboriginal Land Rights. The campaign morphed from ‘Joh for PM’ to ‘Joh for Canberra’.

On 11 May 1987, ABC TV screened a Four Corners program named ‘The Moonlight State’, which was a brave expose into Queensland’s decades-old activities of illegal prostitution and gambling, aided by police corruption that reached all the way up to the police commissioner. The premier at that time was in the United States. Within a day or so the Acting Premier, Bill Gunn, ordered a commission of inquiry. Joh was in Disneyland at the time it was announced. Ian Callinan QC drafted the terms of reference. Callinan was also a Trustee of the Gallery.

On 27 May, the Premier was still in the United States when Prime Minister Bob Hawke called a double dissolution. That sank Joh’s delusional aspiration. He didn’t have a federal seat to stand in.

The Fitzgerald Inquiry was established to investigate high-level corruption in response to such media reports. It seems unnecessary to restate the chronology of what happened. Suffice to say, the Premier went nuts, behaved more erratically and had no control over something the government had commissioned.

The second half of 1987 was a political madhouse. Joh tried to sack a group of ministers, but the State’s Governor wouldn’t agree. On 27 November the parliamentary party shafted Joh 39–9, and for days afterwards he still claimed he was Premier.

Mike Ahern was now Premier of Queensland and Minister for the Arts. There was a sense of relief that permeated throughout government and the public service. There had been a palpable sense of being watched by ideological eyes. And in many cases that was true. My curator of Australian art had once been taken out for a drink by members of the Special Branch. It was to check on his ideological soundness.

None of the mayhem bothered me. I was left unencumbered by any political imperative and given a long leash to implement change and rethink the Gallery.

But some things were tricky — prospective Gallery sponsors, private or corporate, were cautious. While wanting to support the Gallery, they were uncertain about such financial support being seen as offering a default approval of government. Like everyone else, they wanted an election.

World Expo 88 preoccupied Brisbane for half the year. The Queensland Cultural Centre, which included the Gallery, was located next to it. The Gallery’s architecture is one of Australia’s finest works of concrete minimalism, commissioned by one of Australia’s most reactionary governments. The QAG building is important for its considerations of how a contemporary art museum might function. It was certainly the first in Australia to recognise that the phenomenon of the ‘blockbuster’, and intense exhibition programming, wasn’t going away. It was a fabulous building to work with — its logic and clarity of expression is pristine. Its large temporary exhibition space was in the centre of the building and built for purpose.

Since London’s Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851 and all those International Exhibitions which followed, the blockbuster exhibition has been well and truly ensconced as part of civic self-esteem. The phenomenon of the blockbuster as being critical to art museum conduct has raged for the past 40 years. Exhibition programming has influenced changes in art museum architecture more than most other aspects of their conduct. The huge rise globally of biennials and triennials is something of an echo of the colonial idea of acting locally and embracing the world.

When the Queensland Art Gallery (QAG) opened in 1982 it was said to be Brisbane’s coming of age. In fact, most things that happened in Brisbane were a coming of age. What does this mean? What does it say about civic self-doubt, or parochial self-importance? The Commonwealth Games in 1982, a new airport in 1988, Expo and, more recently, a Ferris wheel — a heritage modernist experience from 1893, Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition — are markers of coming of age. Very odd.

Until 1982, the Gallery never had a purpose-built permanent home. Now I had the opportunity to rethink almost everything about what its future might be. And staff were exuberant with the opportunity.

Australian state galleries were creations of the nineteenth century, and Queensland’s is one of the youngest. It collected in the longstanding and traditional areas of Australian, British and other European art, but could never compare itself with the expansive, sometimes encyclopaedic character of its sister institutions, especially the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the National Gallery of Victoria. There were subtle and interesting distinctions to the Queensland Art Gallery’s collections. Nonetheless, the Australian collection was of lesser quality in comparison to the collections in regional centres, such as Victoria’s regional riches of Ballarat, Bendigo and Geelong.

But if the Gallery wanted to play catch-up and try to become a mirror of its sister institutions, it would diminish its reputation. Major artists were represented with relatively minor works, and quite a few artists who paved the way in Australia, such as Eugene von Guerard, were not represented at all. There were no epic Heidelberg School narrative works either.

If there were to be an historical regional emphasis, what might it look like? I posed the challenge, ‘Name the ten finest nineteenth-century Queensland painters’. I couldn’t find anyone who could name ten, let alone the finest. Lesser-known artists were collected because a state gallery must also be local. And acquiring contemporary Aboriginal art happened relatively late in the piece. Any prospect of becoming a timid version of other state galleries made no sense. Masterpieces were rare. We couldn’t collect in depth and tell a coherent story, and we would pay exorbitant sums to collect lesser works by major artists.

The best-known aspects of the Gallery’s Asian collections were Edo ukiyo-e woodblock prints, a collection of netsuke and objects from various places but without a coherent thread. It was the familiar museum predicament of a collection derived from occasional purchases and private bequests. But it continued to put together very fine vignette Asian collections. These included Japanese, extending the ukiyo-e print collection and purchasing masterpieces from the Six Old Kilns of Japan — Shigaraki, Tamba, Echizen, Seto, Bizen and Tokoname. These connected nicely with a good collection of Australian pottery from the 1950s and 1960s. In other words, the Gallery began to collect disparately but in more tightly focused fashion than it had in the past. Contemporary Asia would soon follow.

Queensland developed Sister State, or Prefecture, relationships — Shanghai and Saitama (an hour from Tokyo) were two important ones. Institutions tend to baulk at the obligations expected with such arrangements. But they can work and work well. In late 1987 the Gallery co-curated a large exhibition of contemporary Australian art which was presented at the Museum of Modern Art, Saitama. In return, QAG presented ‘Japanese Ways, Western Means: Art of the 80s in Japan’ in 1989, curated by Saitama staff, and purchased work from it for the permanent collection. Today it’s an exhibition title which makes little sense, and that was probably the case then.

An important exhibition of historical work was drawn from the Shanghai Museum. In return, a hugely well-received exhibition of contemporary Australian jewellery was presented in Shanghai.

***

There was no logical historical connection the Gallery had with the arts of Asia. The idea of the Asia Pacific Triennial was a construct: just that, an idea. I’d become consumed by the observation that as the twentieth century marched on, Western museums collected less and less Asian art of its time.

In December 1989 the inevitable happened: a Labor government was elected, and Premier Wayne Goss took on the arts portfolio too. Many people think that marked the triumph of good over evil — well, that’s largely true. The Premier’s Chief of Staff, Kevin Rudd, sent Bjelke-Petersen acolytes to what was colloquially known as the Spring Hill Gulag. Two-thirds of public servant heads were isolated there.

After the demise of what former Labor Federal Prime Minister Gough Whitlam called the ancien régime, a sense of new possibilities took hold. The APT, a major project, and the idea that something emerging from a small base and might fail, is not a common part of current museum practice when pitching for funding ideas. Premier Goss’s reaction was telling. He told me he took on the arts portfolio because political and administrative reform was certain. He wanted Queenslanders to think differently about themselves, and ‘that’s where the arts come in’. I worked closely with Goss then, and later, post-politics, when he became my chairman at the Gallery.

When I went to see him as Premier in 1990 to ask for a lot of additional money for the first APT, he thought it was a risk, but an acceptable risk … and gave me the ex-gratia grant of $600 000 I asked for. The concept of regional cultural diplomacy wasn’t lost on him either.

What marks the APT as different from the proliferation of other biennials and triennials over the past three decades is that it is institutionally based, becoming inseparable from the conduct of a well-established art museum. It was neither conceived as a project of gratuitous cultural-dollar-grandeur (as some blockbusters have been, and I can plead guilty to that) nor as an effort at soft diplomacy. In fact, we weren’t sure what we were in for, and we announced we’d do a set of three over 10 years and if they failed, we’d end them.

In Australian collections, Asian art was largely art history. The more Asia changed and became interested in ideas beyond its traditional cultures, there was a corresponding decreasing interest in what Asian artists produced — and they weren’t collected. Internationalism was seemingly the prerogative of the West’s alone.

To deal with geo-cultural specifics, for APT we established a national consultative committee. It offered informed project guidance with no role as curatorial selectors. It included Gallery staff, a regional gallery director, Director of the Canberra School of Art David Williams, Asialink Arts’ Alison Carroll (University of Melbourne), Neil Manton from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and other occasional participants. One of its earlier meetings was in Kuala Lumpur. Thailand’s renowned curator Apinan Poshyananda attended, along with our Malaysian colleagues.

There was no uniform or rigid organisational model — it had to be flexible. Developing relationships and, eventually, pulling together the logistical arrangements was never going to be the same in Vietnam as it was in Korea.

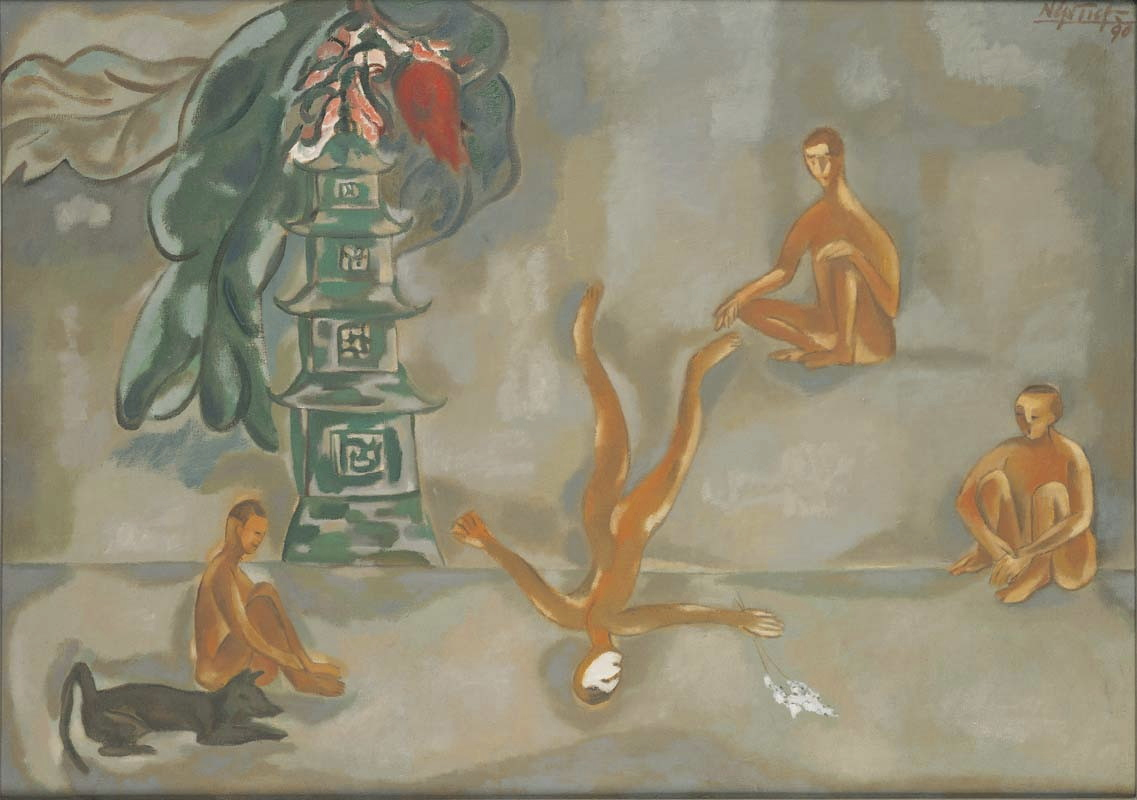

Xuan Tiep Nguyen / Vietnam b.1956 / Song of the buffalo boys II 1990 / Oil on canvas / 85 x 120cm / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 1993 with funds from The Myer Foundation and Michael Sidney Myer through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © QAGOMA

Xuan Tiep Nguyen / Vietnam b.1956 / Song of the buffalo boys II 1990 / Oil on canvas / 85 x 120cm / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 1993 with funds from The Myer Foundation and Michael Sidney Myer through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © QAGOMAEqually, it’s important to observe that certain Western typecast ideas of what contemporary art might look like in Asia was going to mute expectations. Vietnam easily accommodated the high modernism of the School of Paris with culturally specific folk and colloquial figuration.

Unlike in the Venice Biennale, countries were not represented by artists. APT represented the work of artists who lived in particular countries. Some post-Tiananmen Chinese didn’t live in China. The assistance and support of various government agencies was welcomed, but none had a role in selection. This was not always an easy undertaking.

Well-established protocols of curatorial conduct expanded into a new model. Some staff across disciplines — all with art-historical backgrounds — would perform curatorial roles, each with important curatorial contacts in particular countries. Some were informal, others connected with institutions. It was relationship-based, where local voices were heard; local cultural politics somewhat understood; and where the APT didn’t brazenly invoke its Western-dominated imprimatur.

The Pacific required a different approach. Despite our wish to make everything happen in person, the vastness of geography and logistics meant that for the first APT, extensive curatorial travel and visits were not possible. That would later change. But in 1993 our relationship with the Pacific was mediated through New Zealand and its well-established networks and deep understanding of cultural contexts. Queensland itself had a close-knit Pacific community.

The APT was speculative and not risk-averse. We sought to engage people directly and had a substantial budget for curatorial travel to each of the participating countries, so that unofficial and interdependent connections could be established. Above all, we wanted to connect the ideas and the institution to people in a collegial sense. That’s why we had a large budget line allowed for bringing artists, writers, curators and others to Brisbane. And why we took the risk of being a venue for ambitious projects that artists wanted to undertake but had never had the opportunity to realise. It was important to bring — at the Gallery’s expense — as many artists as possible to Brisbane.

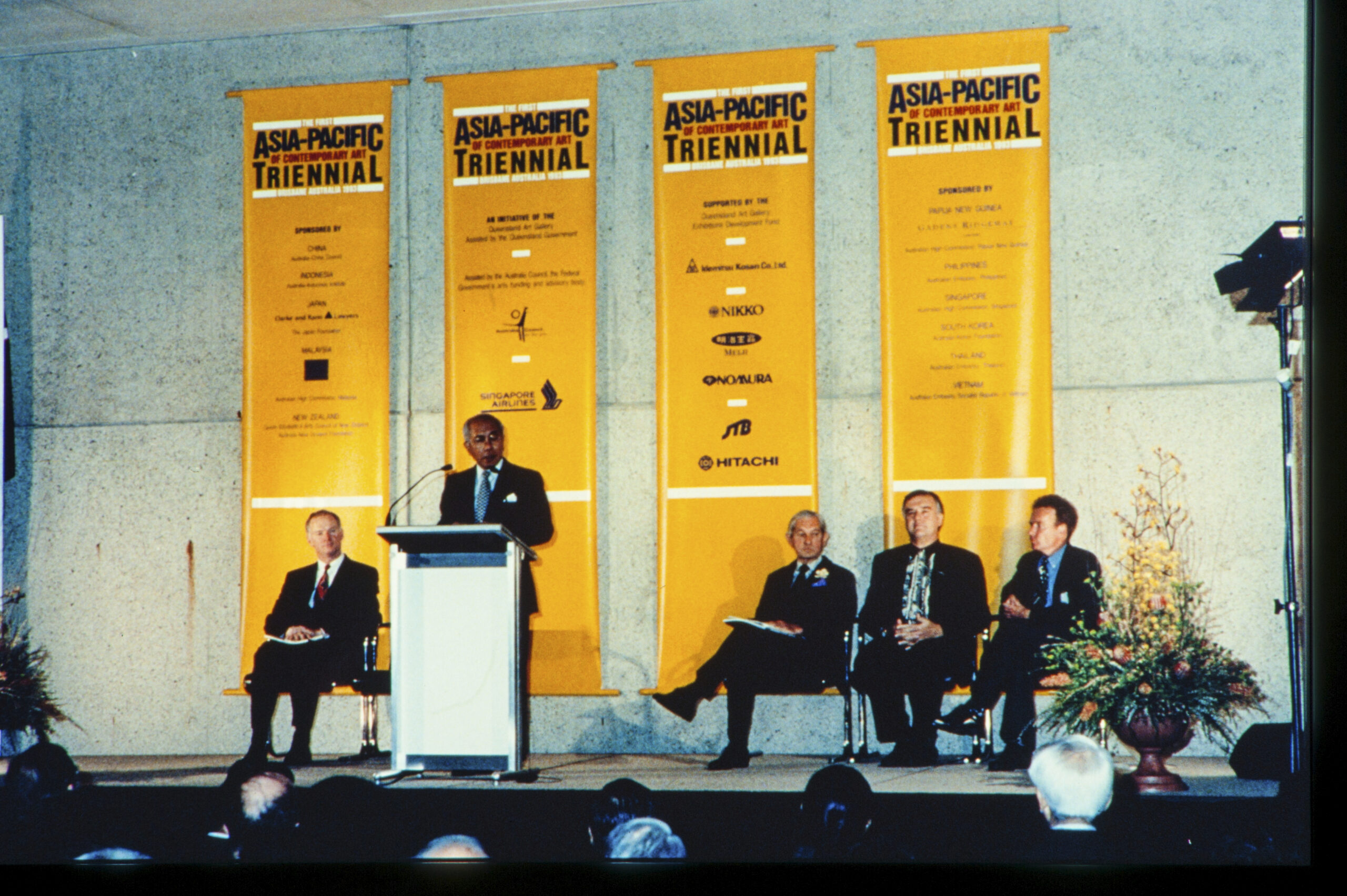

After years of planning, APT1 opened on 17 September 1993 and ran until 5 December 1993. Its legacy endures within an art-museum context, not as an event that lingers in one’s memory or through ephemera and publications that underpin a particular cultural moment. The APT had a few early doubters who later became its strongest advocates: the records reveal waverers eventually becoming vigorous devotees.

The purchases of works of art made for APT 1 helped consolidate the dovetailing of a major project and the way the Gallery would operate. It developed a distinctive cultural mindset that spread across every department. Works across all media were acquired by artists from every country. Trustees never rejected a curatorial proposal. It was a case of trustees and professional staff in cultural and institutional alignment.

Indonesian artist Dadang Christanto’s For those who have been killed 1993 was a moving installation that included a performance component. It was a haunting work about Indonesia’s missing people, including the artist’s father, who were targeted by previous government authorities, and the Gallery acquired it. It was also a participatory work for the public: private notes made by visitors were left under a suspended bamboo arrangement and collected daily.

***

At the time, the APT was viewed as an unclear venture as the Gallery sought to identify a unique international role without aping the activity of other state or national institutions. Governments of all persuasions embraced and used it intelligently as a marker of cultural diplomacy of what the State of Queensland might represent.

The scale of the APT was ambitious, but it didn’t emerge from a vacuum. Australians such as author and then cultural counsellor Nicholas Jose, and art historian Claire Roberts, were in Beijing in the late 1970s and 1980s, and were deeply engaged with the contemporary art scene. Their intellectual and practical advocacy for artists was hugely important. Claire curated the important exhibition, ‘New Art from China: Post-Mao Product’, which toured various Australian venues in 1992–93.

Xu Bing / China b.1955 / A book from the sky 1987–91 / Woodblock print, wood, leather, ivory / Four banners: 103 x 6 x 8.5cm (each, folded); 19 boxes: 9.8 x 49.2 x 33.5cm (each, containing four books) / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 1994 with funds from the International Exhibitions Program and with the assistance of The Myer Foundation and Michael Sidney Myer through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Xu Bing

Xu Bing / China b.1955 / A book from the sky 1987–91 / Woodblock print, wood, leather, ivory / Four banners: 103 x 6 x 8.5cm (each, folded); 19 boxes: 9.8 x 49.2 x 33.5cm (each, containing four books) / The Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Collection of Contemporary Asian Art. Purchased 1994 with funds from the International Exhibitions Program and with the assistance of The Myer Foundation and Michael Sidney Myer through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Xu BingEarly in the piece, word spread about the APT’s aspirations. I remember being in Tokyo in late 1989, four years before the first APT, and being told that a few Tiananmen self-exiled Chinese artists were in the city and wanted to meet me. The Gallery’s intentions were already being talked about. I was tracked down by Gu Wenda, Cai Guo-Qiang and others. In a sense, that’s a marker of the Triennial’s conduct. There was no convenient pre-existing network, and the informality of relationships that developed set a pattern of how things would be done.

What emerged from this was a distinctive ‘personality’ which the Gallery enjoyed, especially the ease with which it undertook projects which were speculative. In later APTs it was prepared to look retrospectively, to think about artists — Lee Ufan is an excellent example —who were well regarded but had remained distant from serious accounts of late twentieth-century non-Asian art and deserved to be part of a fuller international story.

It’s self-evident to note that the contemporary Asian art market took off and overheated. In the space of a decade QAG was in the hypothetical position of being unable to go out and buy the collection it already owned. In some cases, the Queensland Art Gallery was the first major Western museum to exhibit or collect substantial work by artists such as Cai Guo-Qiang, Xu Bing, Montien Boonma, Takashi Murakami, Lee Bul and Zhang Xiaogang. Artists were helpful in accommodating a public Gallery’s limited acquisitions budget. Yayoi Kusama is well represented, including a major room installation Soul Under the Moon 2002. Ai Weiwei was first collected before his near-cult celebrity status took hold. And QAGOMA’s Research Library is vast.

The APT was the product of a cultural policy imperative, an institutional realignment and how the Gallery sought to avoid becoming a pale reflection of other Australian curatorial conduct. It never tried to match what other collections had brilliantly achieved and which it had no chance of emulating.

Perhaps the most unanticipated characteristic of the APT was its broader public reception. A couple of decades earlier, most people would have accepted the one-liner that the public doesn’t respond to contemporary art. Any market testing would have concluded it would be an expensive folly. But what’s fascinating is that new art, made by artists the broader public had never heard of, from cultures they often knew little about, aroused considerable curiosity.

In 1996, Nicholas Serota, then Director of the Tate Gallery, London, gave a lecture titled ‘Experience or Interpretation: The Dilemma of Museums of Modern Art’. He spoke of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, which opened in 1977, that sought to establish a new model for the interaction of creative disciplines in the twentieth century: an open museum, a place where there is a natural contact between artists and the public in developing the most contemporary elements of creativity. He closed his essay with this final paragraph:

Our aim must be to generate a condition in which visitors can experience a sense of discovery in looking at particular paintings, sculptures or installations in a particular room at a particular moment, rather than finding themselves standing on the conveyor belt of history.1

The first APT opened with close to 200 works by 76 artists from South-East Asia, East Asia and the South Pacific. And it grew exponentially from a beginning that drew interest not only locally and from the region, but also from North America and Europe.

Lee Bul / Korea b.1964 / Fish 1993 / ‘The First Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT1), Queensland Art Gallery, September 1993 / © Lee Bul

Whatever expectations people might have had about historical Asian continuity were, on occasions, ruptured. Korean Lee Bul’s performance in APT1, Fish 1993, made an amusing and poignant point about cultural and gender constructs. The opening crowd knew nothing about the planned and unannounced performance. It was an ongoing sequence of clothes-swapping involving audience participation. At the end of the performance, the artist was wearing none of her own clothes. Many in the audience had to find and negotiate the exchange of their own.

To invoke a cliché, the excitement and energy levels surrounding APT1 were high and people were keen to be there from the start. The RSVP list was so large that the official opening had to shift to being outside the Gallery, to an underpass with its normally busy road closed off.

The APTs have always included Australian art. And this poses the question of why so few Asian Australians were included. It was a deliberate curatorial decision not to make the exhibition about ourselves. They were other exhibitions, and a separate collecting activity. The focus was to be elsewhere — Australia as one among equals.

***

The Queensland Art Gallery had begun to buy contemporary Asian art, mainly Japanese, before the first APT. It was always planned that each Triennial — and the activity in between — would provide an opportunity to acquire work for the collection. As we know, the APT didn’t cease after its third iteration. It became central to the Gallery’s role and reputation. It was also the cornerstone of advocacy for the case for a Gallery of Modern Art and this enjoyed bipartisan political support.

The success of early APTs was central to a separate purpose-built gallery to sit alongside QAG. The idea of a second gallery took a long time to realise — about 16 years from first thoughts to official opening. When Pauline Hanson’s One Nation won 11 seats in the state election of 1998, Labor ruled with the support of an independent. One Nation’s support base was largely regional. Premier Beattie told me that he couldn’t announce so much money going into South Brisbane for a Gallery of Modern Art. He said it wouldn’t last, to quietly get on with things and say nothing, that after the next election he’d come to the gallery and announce GOMA. He did. After the next election, One Nation had three members and a couple of weeks later Beattie came to the Gallery to announce GOMA was going to happen. The ambition and success of the APT series convinced government supporters that the show needed its own modern gallery to do it justice. QAG was the first state gallery in the country to have a second building for contemporary art.

The media offered nothing but straightforward reporting and support. APTs aroused curiosity locally for an exhibition where, for the general public, artists were unknown, cultures not fully understood and where the more you knew, the greater the experience.

The collection developed, Asian programming between APTs increased and interests ranging from government, academic, museums and commercial were consolidated. Its success attracted international interest. In 2002 I was asked to speak at the Association of American Art Museum Directors Conference in Honolulu. How did the APT happen; how did it become the cultural marker of the Queensland Art Gallery’s international profile? I recall the comment of one museum director whose Asian collections were regarded as one of the finest in America. It was more a lament than comment: ‘We have 4000 years of Asian art history and nothing after 1930’. The example of the APT was to help in changing that. The idea that the West changes, effortlessly internationalises, and that Asian cultures must be true to their heritage and fodder for the West has collapsed in the past three decades. A particular art-historical imperialism has vanished.

The APT came to represent the Queensland Art Gallery, not only as an event but also as an enduring commitment to our region. Many professional and museological practices altered because of the APT. Changes happened from within and not always observing and taking the exemplar of others.

Anish Kapoor / India b.1954 / Untitled 2006–07 / Resin fibreglass and lacquer / 500cm (diam.) x 555cm (installed) / Commissioned 2006 with funds from the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation in recognition of the contribution to the Gallery by Doug Hall AM (Director 1987–2007) / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Anish Kapoor

Anish Kapoor / India b.1954 / Untitled 2006–07 / Resin fibreglass and lacquer / 500cm (diam.) x 555cm (installed) / Commissioned 2006 with funds from the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation in recognition of the contribution to the Gallery by Doug Hall AM (Director 1987–2007) / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Anish KapoorOne thing that pleased me most when I left GOMA — 20 years to the day after I had arrived — was my farewell gift. But it wasn’t for me. Anish Kapoor was commissioned for a work in recognition of the Gallery’s commitment to the region and my role in it. He made a huge work, and it was pretty much done and delivered at cost.

If there’s a marker for the first APT and those that followed, it is reciprocated generosity. The APTs were never exercises in doctrinaire ambition, but careful and considered projects in profiling what is important and unfamiliar. As Wayne Goss said, it makes us think differently about ourselves.

A version of this text was first delivered by Doug Hall as part of the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne’s Lecture Series, ‘Defining Moments: Australian Exhibition Histories 1968–1999’, on Monday 24 August 2019. The author acknowledges Max Delany’s support of the original piece.