Roundtable

Making work as part of the diaspora in Australia

Sana Balai, Brian Fuata, Taloi Havini, Salote Tawale and Ruth McDougall

(left to right) Salote Tawale, Brian Fuata, Ruth McDougall, Taloi Havini and Aunty Sana Balai, Cleveland, 14 March 2021 / Image courtesy: Sana Balai

(left to right) Salote Tawale, Brian Fuata, Ruth McDougall, Taloi Havini and Aunty Sana Balai, Cleveland, 14 March 2021 / Image courtesy: Sana BalaiThis discussion between Pacific elder and curator Aunty Sana Balai and artists Brian Fuata, Taloi Havini and Salote Tawale occurred between 13 and 14 March 2021 on Minjerribah (Stradbroke Island) and in New Farm, Queensland, coordinated by Curator of Pacific Art, QAGOMA, Ruth McDougall.

Brian Fuata: Testing, one, two, three. Hi, how’s it going?

Salote Tawale: That was like the beginning of a Brian performance.

BF: [Laughs]

Taloi Havini: Since Campbelltown and your performance at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, whenever I hear you on a mic I just think, ‘This is a Brian Fuata performance’. [Laughter] It’s like your voice is a material.

ST: Well, what a great segue into how much our body and our identity is our source material.

BF: But also like our art material, like a physical material to mould — to turn raw material into something, like into an art object, right?

ST: Yeah, and something that you, on the one hand, know so intimately, but on the other hand it is like an experiment … about what unfamiliar thing might come from that.

BF: It makes me think about how we as PoC [people of colour] artists work with impulse, with improvisation, or things that are kind of presented to you. It’s a basic question, but how does that resonate to you? What steps are taken to make that unknown thing not freak you out? What’s your coping mechanism?

ST: This is a little bit aside from that, but I think that materiality is so important. The body is a material. Identity is a material. As a person living in the diaspora, making work about what that means — and that’s definitely about being on unceded territory from an island far away, but also, having grown up here, it’s about being from here as well, and from other places — I am always conscious of that image. The image of the materials. The image of the body’s gestures. The body as a material, our culture as a material, will always speak to being from an elsewhere on this land. This is because of who we are, who we look like and who we maybe don’t look like.

TH: I think that is what separates a lot of artists. Diaspora artists are always conscious of being separate from the non-diaspora.

ST: But I also feel like everyone is diaspora. For me, it is like being here but being from somewhere else as well. And so, in that theory — which is quite broad — everyone, unless you’re indigenous to the country you are on, would be diaspora in a way. Taloi, earlier today you were recounting when somebody said to you, ‘Oh, where are you from?’, and when you told them you live here they’re like, ‘No, where are you really from?’ And it’s like, ‘But where are you really from?’ And people who ask that question, they are a couple of generations down from somewhere else. They are diaspora. It’s just that the colonising culture is cloaked in invisibility, masked as a universal normal. We can see it — luckily, it is not normal for us.

BF: I think that is what I find interesting in relation to the Australian context and something that you brought up around identity and our bodies. I think of our bodies and the affect of our bodies as a material. Because we then have to ask us ourselves, what is that on unceded country? And I think about Samoan-Australian performer Tommy Misa’s performance I saw a few years ago, where they were referencing Samoan Mau protests — or maybe it was like a breakout, like some flu from the 1800s or something like that — and they were talking about this transgenerational effect, but that was ceded in their body. But then how do they address that trauma on unceded land, of being a guest on country? How do they foreground the present trauma of Aboriginal Australia? How do they prioritise it? And when you ask what diaspora is to us, I think there’s a universal textbook academic definition of that, but then the Australian context does something particular to it. But that is something particular not only to the diaspora of all ethnic races, but also specific to our Pasifika-ness. And I’m not sure what the answer is to that, but I like it as a point of departure.

ST: Or as something that we need to sort out.

TH: Right. I actually agree. Salote, I’ve heard your idea that we are all diaspora, about think it is a very unique way of thinking about it. That’s how you feel about the word and the concept and how it’s used — as Brian talked about in terms of identity, of Pasifika-ness. We can relate to that when people call us part of that. You know, it’s a classification of where you are assumed to belong. Your definition, Salote, is sort of pushing against that belongingness, or like classification of who is from where, except for the First Peoples of this country.

But that’s reminding me also about working with and talking to people in cultural institutions, in galleries and museums. Them saying, ‘We should make this Pacific collection relevant to the diaspora’. This blanket term! Then, when you say to someone who says that, ‘Well, you know the diaspora that you just mentioned is made up of people with different definitions of what it means’.

ST: That’s interesting you say that, because there’s quite often people who talk as if for the whole diaspora. And I am always conscious that I can only really speak from my own experience and perspective of that. But of course, I’m drawn to other people who make work about what their experience is, because we are still trying to figure out what that means. It’s about context. And so, I just love that you said that, because I think we are from so many different countries. And we also are, you know, often lumped into …

TH: Geography, is it?

ST: Well, I remember people would also lump Pacific and Indigenous Australian people all together, as if we could speak for Indigenous Australians. It’s like, no, there’s a really different perspective here; we are on unceded territory, we have come to this land after, theirs is a different kind of history than ours. As time has passed, more people can see that. You are saying that, and we are all agreeing — ‘Yeah, we’re the diaspora. We’re living in the diaspora’ — but added to this we also come from very different places, but have similarities, and maybe we have shared histories that are thousands and thousands of years apart.

TH: What we are talking about here is difference. And that is what you said yesterday about the importance of difference and cohesion. The first I heard of the term diaspora was in other countries and contexts, like the Indian diaspora in North America. Then here other people put me in that category. But the thing is, I never said that I was diaspora. And when you think about it, it was like, well, actually, I came here as an exile. If we are going to be really specific and get down to how you came to be where you are, my family was exiled. We weren’t refugees. You know, that question we get asked a lot, how did you come here? By choice? Did you get forced? What level of arrival are we talking about? And now suddenly, I am in the diaspora. And the thing you said about time …

BF: Oh, that’s amazing, because it really does tap into what you originally defined as diaspora being about coming from elsewhere and yet from here, too, right? Because now you have opened up the question, ‘How did you get here?’ There are the different technologies of ‘how’.

For example, my experience of diaspora is a typically Trans-Tasman migration story. I’m from the ‘islands’. My parents moved to New Zealand in the early 1970s; they weren’t born and raised there. They weren’t overstayers, they were workers. And then New Zealand became too small for them, so they moved to Australia. So, my understanding of diaspora is like this postcolonial multicultural situation that has diluted the original position of my Samoan-ness. I am a ‘full-blooded Samoan’, yet, if I went to Samoa, they’d be like, ‘You are not from here’. And for me, that personifies some kind of idea of diaspora. However, how I came to this country is different from how you have come here. And yet we are both labelled under the umbrella of ‘diaspora’.

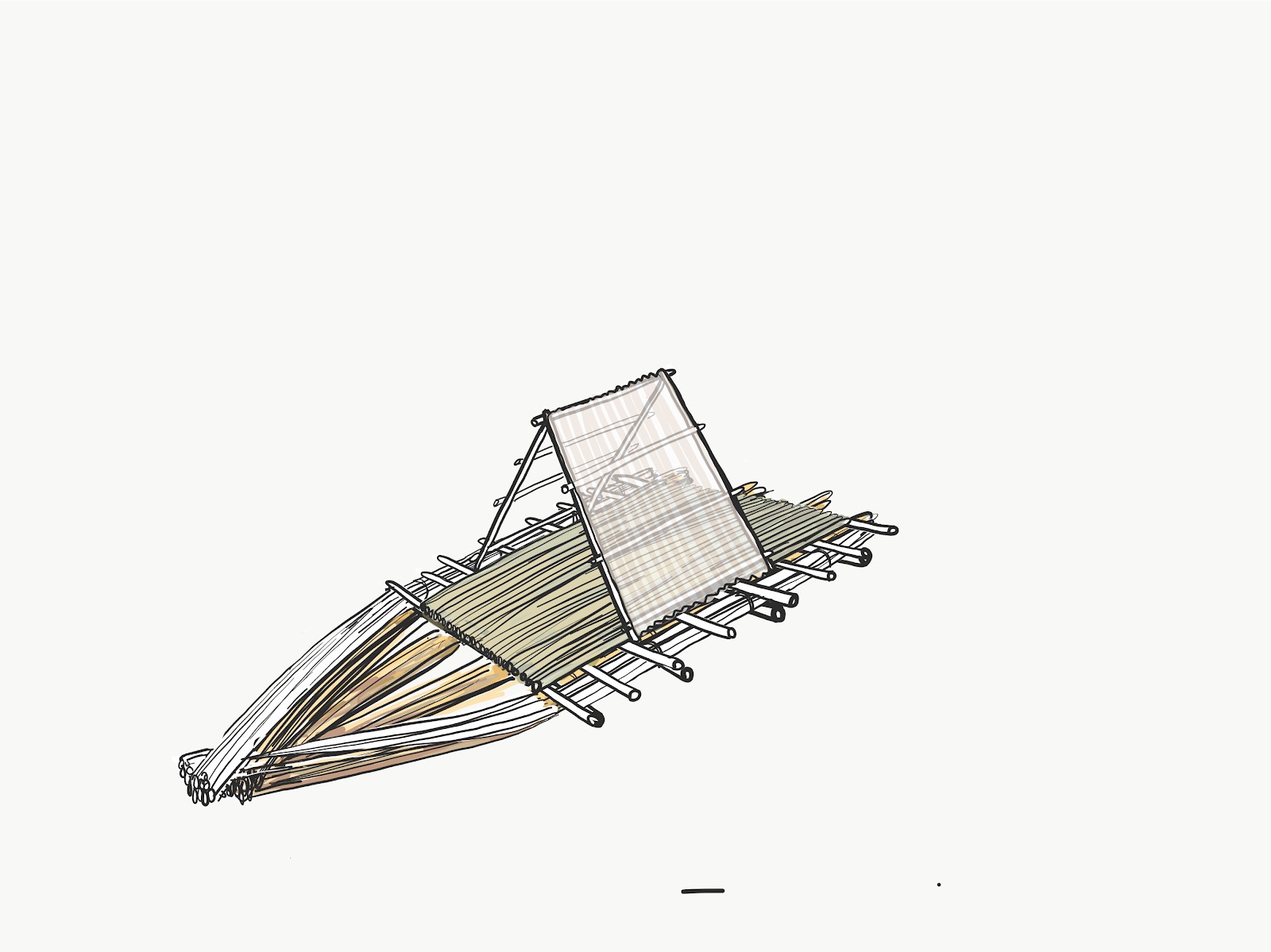

ST: My mother was a Christian missionary who stopped in Fiji on her way back from South America and ended up staying in Fiji and got married. There are all these really different stories. So actually we’re not talking about homogeneity, we’re just looking to acknowledge and to say something as simple as I am not just from here. ‘Here’ is a location that I am in right now, and I’m also from there, and there, and maybe over there. Because it isn’t even that binary either. So, for my Asia Pacific Triennial [APT10] work, the boat I am making is about this experience as a young child of going and seeing a bilbili (Fijian raft) in the Fiji Museum, and thinking, ‘Oh, that’s where I could live’. I could live in between the islands and Australia on this boat, and I could go and visit. I still remember that so strongly. I prefer the diaspora definition to be as simple as possible.

BF: What I love about that not from here / from there, but here concept is that ‘there’ is also not ‘here’. Samoa has gone through so many kinds of colonial administrations that Samoa is not Samoa. ‘There’ isn’t ‘there’. And ‘there’ isn’t ‘here’.

ST: I also love what you said about these different stories, of you being full-blooded Samoan but not having lived ‘there’ for so long. And, for example, my mum has a settler-colonial English, kind of French–Swedish heritage. And I have lived in Australia most of my life, but I was born in Fiji. And there are people who were born here, but that does not tell you how distant or close you are from culture at all. Because the personal stories relate so much to what’s going on in your family — how much you visit here and there, how much you have to find out through other sources, such as archives.

But how much do you understand in that archive based on your relationship to there? Nothing can be said or lived with homogeneity because there’s so much nuance, which makes thinking about artworks made from that standpoint of being in the diaspora in the Australian context so interesting. Works are not going to be the same. There will be things that are reminiscent of each other, and there’ll be similarities in that understanding of this idea of being from there and being here right now, but there’s going to be so much difference in that.

Aunty Sana Balai: One of the things I often think about is how we are now in a stage where there’s a lot of mixing of blood.

I come from an era when culture was very prominent. Government colonisation was making its way and Christianity was coming in, so we had to navigate our way around this without cross-pollinating one or the other.

We are now in a stage where we need to have this conversation, because as you’ve said, Brian, you’re a whole Samoan. With Taloi and Salote, I hope that we can have this conversation where we address what we need to take with us. One of the things that is often missed and — I probably keep harping on this — is that culture evolves.

The foundation is the same, and each generation puts their stamp on space and time in that era. So, the question I often ask myself is, ‘Why should the likes of you, Salote or Taloi, choose which culture to choose?’ Why not navigate and weave yourself within these cultures that are in your DNA? You should feel free to dive into these cultures knowing they are yours, because you’ve got the bloodline from Fiji and Buka and it’s yours. No question mark. Why don’t you just embrace what feels comfortable and what makes you, and that you identify with?

ST: That resonates with me so much. What I thought about while you were talking is that as an early maker, I was trying to work out what I was making artwork about, and as time has gone on, I have had the realisation that as an intersectional person — I am Fijian, Australian, a woman, a woman of colour, a queer woman — that just exists within me. And so, in making work, my body is a material and there is meaning in just that, but also the gestures I make with this body. It comes back to the fact I can’t not be Fijian. I can’t not be settler colonial heritage. I can’t not be any of those things that are a part of my heritage. The strongest works, I think, come from just making from your own position, whether you’re using your own body in it or not.

BF: Can I just also add that my statement of full-bloodedness was both a satirical and critical position. It was made to question the idea of authenticity and an originary space. I am full-blooded, but some might call me a coconut — brown on the outside, white on the inside. And so, my performance, the materiality of my performance, that is not Samoan — being an anti-performance of Samoan-ness is also a diasporic condition.

ST: And it’s a Samoan performance because you are performing it, and you’re performing it from that position of where you are.

In making artworks, we are producing culture. And once again, we are looking at these kinds of differences. You are making an artwork but you are also making something that’s a commentary, and that becomes a part of culture. That is just the way it is. And I think then it is hard for me to separate my artwork from what I know culturally. Even though it doesn’t sit within traditional practices or anything like that. That is just what is being made, right?

TH: You know, the thing I love is you can make what you make, go to Fiji, show some people and they will just get it. There is never a question about whether it is traditional or contemporary. They will look at the work and ask, ‘Tell me the story’, and you’ll talk about the stories. Or they might see a performance and say, ‘Oh, okay. Tell me what that’s about’. You know, there isn’t the comment, ‘That doesn’t sit with our preconception’. I mean, I cannot say what it is like from your experiences, but that is what I am saying when I go home and show the Beroana (shell money) 2015 work. People in Fiji just say, ‘Great, amazing, this is beroana. This is not beroana how we know it, but this is beroana.’ And the concept and the stories behind that are not bound by these classifications of where you were you when you made it. Who are you? Is this traditional? There’s no authenticity tick-box.

Taloi Havini / Hakö people / Autonomous Region of Bougainville/Australia b.1981 / Beroana (shell money) II 2016 (installation view) / Porcelain, stoneware, earthenware, clear glaze, steel wire / 51 metres (length); installed dimensions variable / Purchased 2017. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Taloi Havini / Photograph: Natasha Harth

Taloi Havini / Hakö people / Autonomous Region of Bougainville/Australia b.1981 / Beroana (shell money) II 2016 (installation view) / Porcelain, stoneware, earthenware, clear glaze, steel wire / 51 metres (length); installed dimensions variable / Purchased 2017. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Taloi Havini / Photograph: Natasha Harth Taloi Havini / Hakö people / Autonomous Region of Bougainville/Australia b.1981 / Beroana (shell money) II (detail) 2016 / Porcelain, stoneware, earthenware, clear glaze, steel wire / 51 metres (length); installed dimensions variable / Purchased 2017. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Taloi Havini / Photograph: Natasha Harth

Taloi Havini / Hakö people / Autonomous Region of Bougainville/Australia b.1981 / Beroana (shell money) II (detail) 2016 / Porcelain, stoneware, earthenware, clear glaze, steel wire / 51 metres (length); installed dimensions variable / Purchased 2017. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Taloi Havini / Photograph: Natasha HarthBF: And traditional practices are still affixed, but they can also develop.

ST: Maybe it’s not a question of whether something is an artwork or not. Because an artwork — it is just a thing that exists.

SB: Having said what you’ve said, I would caution that there are things that need to be done with respect. And that artists undertake consultations. If you have issues with it, consult with appropriate people or do your research and then produce it, because it is part of you. But when you do it, you want people to know that you have consulted with appropriate people and that you have the right to make the art. In contemporary terms, I think we can easily fit it into the box ‘expression of oneself’. And again, you are crossing the boundary.

The question is where to draw the line between culture and expression of self. Like you said with the beroana, people are accepting of Beroana (shell money) 2015 because you have done it somewhere else — you have lived somewhere else that is not on the island. You didn’t use shell, you used foreign material, and that’s accepted. Again, if you look at how culture has evolved, that is accepted because the concept is the same — it’s beroana — it’s only the medium that changes. When I look back at our history, the concept or the foundation of whatever we do is the same.

BF: This is actually a perfect segue to the questions that you asked, Ruth, around the variations of your name, Aunty Sana. That you have different titles. You have different words for mother, don’t you? Yet, what is constant? What embodies who you are? Your body changes, but then the context also generates a different title or a different relationship. It is similar to this idea of your contemporary reference of traditional practice.

ST: What you said about respect made me think of re-performance. If you re-perform something, the context is changed. Then the reasoning — or, in art-speak, the conceptual underpinning — of its making is not the same. And that to me is maybe the mark of a lack of research, or of disrespect. Whereas with the change in materiality, the understanding and awareness of the context remains. For the sake of this conversation, being in diaspora I think is really important to making something that ensures an understanding of the original, and departure from that to its new purpose, and then what can continue is … what’s the word I want to use here?

BF: Mana. Strength. Power. Respect.

ST: Yes. And respect. Absolutely.

SB: So, I don’t know what happens with Samoan or Fijian culture, but in Buka culture, it doesn’t really matter how many pluses, minuses or whatever you have; as long as you’ve got a drop of that blood in you, you’re from there. And as long as you know your history and your bloodline or lineage, you’re still Samoan. For me, we say Bougainvillean. The challenge we have now is people are using things like money and power to suit themselves. When I was growing up, you always did something mindful of your past and the future. So, it was like you looked to the past to see the future. And therefore, whatever you did for your generation, you always dealt with this respect for the past — the generation before you — and prepared for the generation that comes after you.

TH: If I could be devil’s advocate, what if you did have a drop of this blood but you got completely disconnected?

BF: Good question.

ST: Because that feels like a bit of a journey — to come back to something.

SB: I know my bloodline, even though we’re from Hakö, all the way to Bougainville, and also past Bougainville. As long as you know one relative who was there, or you know the clan, then you become a part of family.

The first thing that we need to look at for the future is the danger of becoming lost in the old ways. We have got a choice: If you hold the culture too tight, you kill it, and this generation is going to miss out. They will miss out on preparing for anything, culturally speaking, for the future. So, we need to address what part of culture we change, and how we change it. Because we have to get it right for the generation now.

I go home and feel I am more Papua New Guinean, I’m more Bougainvillean, I’m more Buka than the Buka people who are living there because they’re more interested in Christianity and Western views.

This is why I am really grateful that Taloi is taking this journey, because at least she is recording what is running out in the village.

ST: But, Taloi, can you actually expand on what you’re saying there? What if you’ve got one drop of blood and you find that out later?

TH: I feel like there are real vulnerabilities among us. And when the strength of culture and belonging is severed, that fall is really full-on, and drastic and disconnecting. And that’s non-belonging and being pushed to the fringes. And I think what is interesting about how that is happening, particularly in Papua New Guinea, is people are pushed to the centre of Port Moresby. There is a whole underground scene of trans and queer people, or people that just don’t fit in with traditional culture — those that don’t want to get married, that don’t want to procreate. So, they run to the city. And, you know, even when you go and get educated, and go away and come back, there are ties that change over time. But, yeah, I find that really complex. And within the diaspora — we all have different definitions and experiences of what that means — we develop new ideas of belonging.

ST: We all came here together today with a kind of belonging to each other … because of a chosen family.

BF: Chosen family … chosen culture.

ST: Our friendship and how we have come together as makers is a real positive for me.

TH: Sana, I asked you to present a talk at Artspace [Sydney], and I left the subject open at the time because it was about acknowledging our relationship and how much of an aunty and a mama you are. An elder. A teacher. A friend. You are one of the old ilk, who spoke the old Hakö with my father, and yet you are a leading curator. So your roles have gone through the full circle of just how important you are to me.

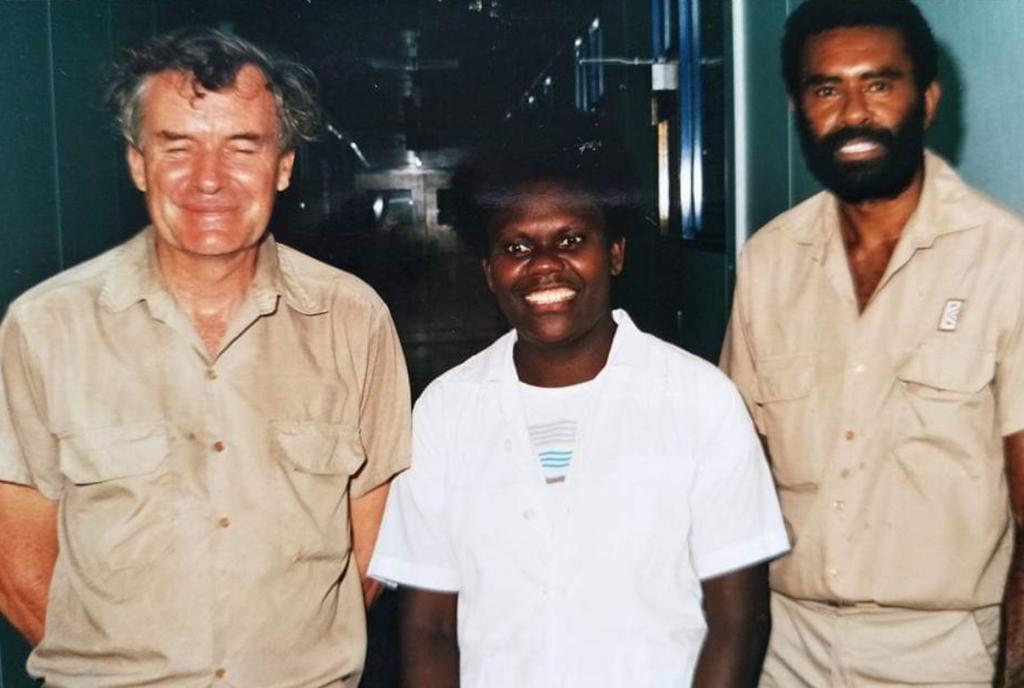

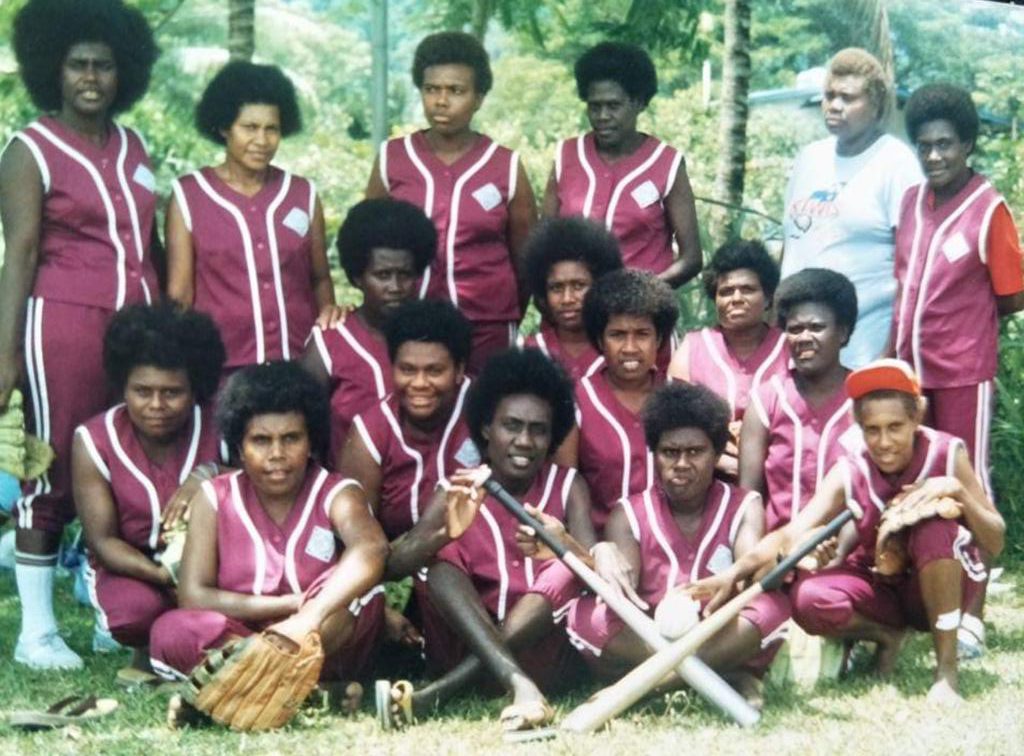

When I asked you, you said, ‘I think I’m ready now to do a lecture performance of my autobiography of my story’. And that’s the most important, powerful thing anyone can ever do. And you did. During your talk, you were able to show photos, but also speak to them, as an experience. You said, ‘This was me playing hockey’. And you know, you’re wearing short shorts and you’re in your twenties or something. And then, ‘This is me working in the Bougainville copper mine as a scientist’. And then ‘This is me at the National Gallery of Victoria as a curator’. And so, your stories are about being fluid and adapting to the people that you’ve met. A lot of us, below you in age, were in that audience, and it meant a lot.

ST: I think because you have been an adviser to our community, a friend to everyone and also probably the least judgemental person that I’ve ever met. When you showed me this timeline of events in your life, it was amazing to hear that story. But it also filtered into all these things I know about you. And it filters into what we are talking about — like the diaspora meaning so many different things. And it is about allowing for stories.

SB: I think what made it right for me was my personal experience from Bougainville, growing up in the 1950s and 1960s and 1970s, and then going to work in the 1970s and 1980s, and then coming here and sharing that experience. Because I grew up in a time where we all knew our own — like Taloi’s father. We belonged to a place where you can go out there and be anything, but you always knew who you were and where you came from. And you knew that when you came back, there was a safe place. Now, Taloi, our relationship didn’t happen overnight. If you remember, I used to say to you, ‘One day I’ll be able to share more with you’. I’ll put it this way: I am the last holder of our cultural knowledge. The one who I got the knowledge from passed away at the end of last year [2020]. The challenge I am now facing is who to pass this knowledge on to, because I am supposed to pass it to someone else — my niece or my nephew. The next generation. And because we have moved away, we are all over the place. And the current generation is more interested in modern life than anything.

The initiation ceremony is no longer practised because of the Church. Until I met Taloi, I always felt that I had failed my peers before me. And as I was getting to know Taloi, over the years, we sussed each other out. And whether we were aware of it or not, I was keeping an eye on her until I said, ‘I think I’m ready. I’m ready now.’ And I think one of the last things I said to Taloi was, ‘I will die tomorrow a happy person because I know I’m able to pass on the culture. Not everything. But just some of the cultural knowledge to you to carry forward.’

Whatever I pass on is what I need to pass — it’s everything that’s traditionally mine and that comes through my line. I have decided that there will be some form of culture to access after I’m gone. And I ask myself what form do I need it to be, what form should it be when I’m gone?

ST: This is interesting because this is a decision you make, but when you’re gone then the decision is sort of no longer yours. And what is passed on will inevitably change, as it has through you. And I think about that in a broader context, in terms of how much culture has been lost since colonisation, and the things that have remained, and the fact that it’s constantly changing, and the things that have been found and brought back. For instance, in our case, the tattoo is this rite of passage. It is revived but is definitely not the same.

SB: That’s normal. What we do here is not same as yesterday. And that’s accepted in our culture. And I am also conscious that it is a big ask from Taloi, because she shouldn’t be burdened with carrying this cultural knowledge.

TH: Oh, thanks — phew.

TH: Just to respond to that, I think that each generation, even in non-indigenous cultures, chooses what they decide to take on as important. Don’t you think?

Multiple voices: Yeah.

TH: And I think in our case, it won’t be language that gets passed on, because I am pretty bad at that. Let’s just face it. But it will be the most important things that our generation thinks. And it will be to do with land, and with caring for that land, and maintaining it. And you can only do what you can do in your capacity, right?

ST: It is interesting that you say it won’t be language, because language is not only a part of land, but a part of everything. I mean that there is going to be a definite change in how we will operate on land. That has to happen because language changes.

TH: Just on that, though. I say it won’t be language, but language will continue because there are native speakers. But it is not something that I personally will pass on. I am making efforts all the time with you, Sana. And I am lucky for that. But, you know, language will be carried forward in its own way, I think — and new language.

SB: Also, if it’s a consolation for you, don’t feel bad if you don’t speak the language because, you know, back home they’re killing the language themselves.

ST: I think that’s happening everywhere.

TH: It is a common story, right?

SB: And it also marks your generation. It’s yours. So, the custom that you practise now, that I’m part of now, is not the same as the custom my mother had. It has changed. My mother had this conversation with us when we were small: ‘Everything is changing, so you have to be prepared’. She used to say, ‘the place is changing’. Wherever you are, it’s evolving. It’s what you take with you that’ll mark your generation. It’s okay as long as the beroana is there.

ST: Because we are talking about the diaspora … As a person who spends a lot of their time here in Australia, Taloi, how do you maintain your identity?

TH: Well, I feel like we all have similar experiences in terms of when an institution asks, ‘Where are you from?’ Someone asked me the other week, ‘How do you identify?’ I was like, ‘What do you mean, how do I identify?’ And they were like, ‘Well, are you a Bougainville-born Australian artist or are you an Australian artist from Papua New Guinea?’ And then you realise …

ST: A model slash actor.

TH: [Laughter] And you realise you are all of these. And it’s like, well, it’s all true. It just depends on how you want to word it. And when you said how do you maintain that here as someone who spends most of their time here …

ST: Well, maybe ‘maintain’ isn’t the word … I feel like I make a different work than an artist in Fiji. A contemporary artist in Fiji has a different context, makes a totally different work.

TH: Would you make the work in Fiji that you make here?

ST: I don’t think so. It is very contextual. And Brian was saying before about when you’re there, you’re Australian, and when you’re here, you’re Samoan. And I think you are talking about different kinds of culture when we talk about diaspora, because we are talking about being here from there and what that might mean.

TH: And also speaking as an artist.

SB: Exactly.

BF: Another thing that your question makes me think about is how culture is transmitted and also received. In terms of my Samoan-ness, I don’t know many traditional practices or anything, and I have not even been to the island. I actually recognise it through my Pasifika community, who go ‘That is so islander’, and I read my Samoan-ness through their appreciation, through their critical review. Another thing, for instance: I remember visiting New Zealand–born Pasifika Samoan poets and writers who’d seen me perform at Casula Powerhouse [Sydney], and they were like, ‘We didn’t know that we were able to do that’. In my diasporic Samoan-ness, I had opened a new Samoan-ness that they had never considered.

ST: That’s context again. You had to be here to be able to do that.

TH: And there’s an unspoken or unwritten sort of knowing of being in the presence of your performance of who you are that they pick up on and think, ‘There is something of our islands in our bodies’.

BF: Absolutely.

SB: I think, at the end of the day, you should have the freedom to express yourself in your own self, provided you do it with respect to yourself and to whatever subject you are dealing with. And if you are referring to that culture, then it should be with consultation. But I don’t see why you should restrict consultation, because one of the things that I’ve experienced with the Pacific community, when it comes to meeting with the younger generation, as soon as we elders come, we say, ‘Okay, this is how it’s going to be’. And you tend to find the younger kids, when they come to meetings with the elders, they are expected to fall in line with the elders. And I’m thinking, ‘Hang on a minute. We’re not in the islands. No, we’re here.’

ST: Two things really stick with me. The first is that we are a part of a legacy. We are in the middle: there are those who will come after us; and we have learnt and been supported by those who came before us. The second thing is there is a responsibility for care. Not only of each other, but caring for how — and it’s probably the biggest responsibility I feel as an artist — am I making this? What am I making this out of? What is my gesture? What is my thought process in this? What is the right way to do this? Because we cannot just make something that looks right; we actually have to make something in the right way.

BF: It is about process and not like simply photocopying something, right?

ST: Yeah, absolutely.

TH: But you are speaking like a true artist. That is how artists always think. You know, you are creating new things. What does that ultimately mean?

TH: And then added to that are your relationships.

SB: And we are now in an era when family is not necessarily your blood family. In here [gestures to everyone], we are family because of the relationships we have formed. So that is one thing we have to be mindful of, because family as we knew it is not going to be the family that we will know in the future.

ST: There is a real multiplicity that you’re talking about there. And I think it extends from not only being from the same place in a regional context or in an Australasian or Pacific context, but also thinking within that too, like queer communities — all of those actual communities that we are part of that that sit across, together and separately. And that is what I think it comes down to as an intersectional person — making stuff from your own place. Working outwards is important, because it always feels wrong to me if I try to bring stuff together that I don’t have a relationship to.

BF: Something that Sana talked about was this new generational shift around what culture is, and complicating it with the idea that tradition also changes. What I have mentioned before was this ideal of Fa’a Samoa [The Samoan Way], where the authentic way of being has now been merged with pure Christian morality. And so there is this kind of crisis around what is Samoan, particularly when the terms by which you are defining it are purely Western constructs. And they have become so hard to extricate now.

Ruth McDougall: Brian, I wonder whether there is a final question around your practice and your engagement with institutions. I am thinking about that beautiful essay you sent me last year about opacity and the way that all of you are working within institutions in a way that is revealing the frameworks and things that are there.

BF: I think this idea of opacity is beautifully connected to this conversation we are having about diaspora. If the diasporic identity is one that cannot be seen because of multiculturalism or postcolonial situations, then opacity becomes a tool to sort of undermine hegemonic structures. So, for me, this idea of almost creating an anti-performance that incorporates what I know and feel is a very Samoan technique of performance. It is very casual, and uses humour, or uses conviviality and weaponises conviviality to disarm these structures or perceptions of what performance in a gallery might be.

I am really interested in refusing to perform Samoan-ness. I literally have got to watch myself. But yet, the Samoan-ness is expressed through humour. It’s expressed through utterance of this — and I remember doing a First Draft [Sydney] performance and Taloi, you were like, ‘You were calling the ancestors’. And again, that is such a beautiful example of how culture — answering your question, Ruth — is revealed in this. In that moment, Taloi revealed culture to me. It was like, ‘Oh my God’. It’s already …

ST: It’s already within you.

BF: It’s also within my community, who are both family and audience.

And there is a reciprocal relationship there that builds. It is generative.

And so, I think my relationship to the institution is also created, like an in-built antagonism that is creative and productive. Otherwise, I would be a depressed emo mess. I think about how can we as Pasifika employ various strategies that either harmonise or weaponise against the institutional structure to create an artwork?

ST: So, you’re saying a tactic of yours is to — I love it — not perform Samoan-ness? This is interesting, because how can you not?

BF: How can I not?

ST: Exactly.

ST: I do think, of course, that you have to perform yourself in that institutional context. Like, it is maybe different from just being here, sitting here together, right? It is like you end up having to be unguarded, but thoughtful in the way that you’re going to not perform your Samoan-ness. That to me is a blaring, awesome gesture to make. Because actually, sometimes, the institution just wants your Samoan-ness.

BF: Exactly.

ST: And it is not like, stop asking me to perform something that is there, but rather, it’s not going to necessarily be there the way that you want it to be.

BF: Exactly.

ST: It is here now. This way.

BF: Exactly.