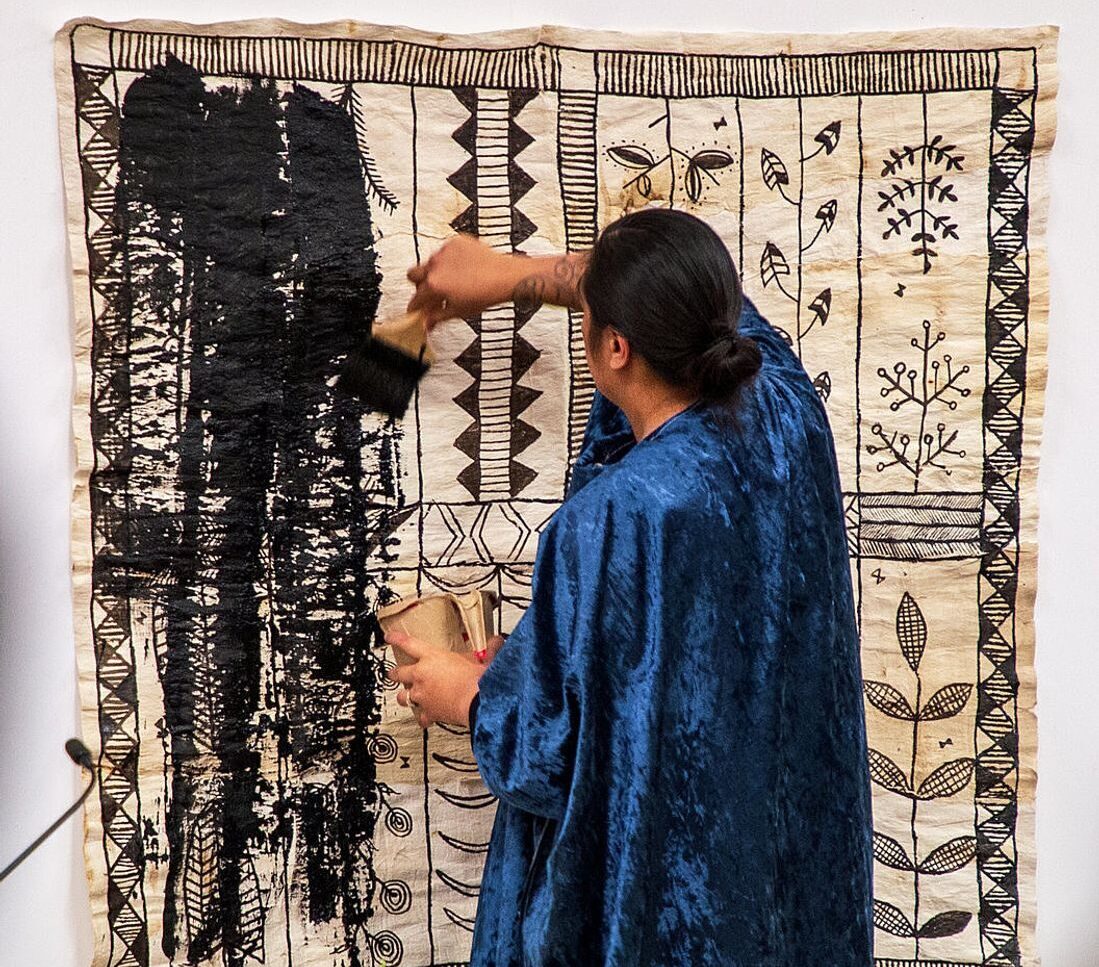

In 2020, as an audience gathered to hear Cora-Allan speak, the artist stood, dressed herself in a blue velvet cloak, took up a brush licked with black paint, and proceeded to paint over her hiapo Our Last Supper with You Revised 2020, hanging on the wall.1 The effect of the spectacle was immediate. Stunned onlookers reacted not only to the performed ‘destruction’ of a work, but the perceived loss of endangered imagery.

Cora-Allan later spoke about her performance in conversation with art critic Lana Lopesi. The artist remarked:

I’ve had to research the crap out of everything, just to find little nuggets of information. Through those processes there is this responsibility of handling, recording and keeping the knowledge, and that performance for me was based on providing insight into how it feels to be me as a maker bringing back an art form. The patterns on that cloth will now have to be remembered by whoever was in the room and saw it first.2

Cora-Allan’s explanation highlights the immense effort involved in learning hiapo (Niue tapa) and the responsibility it bestows. In the act of erasing her patterns, she challenged others to take on the burden of memory. It was also, perhaps, a reminder of how tapa’s material knowledge is transmitted. To learn and remember, you need to observe the art form — and maker — in person.

***

The past few decades have seen a huge resurgence in many different varieties of tapa. The term tapa loosely describes a range of cloth-making practices found across the Moana (Pacific Ocean), in which the inner bark of plants is harvested and processed into a textile. Although many plants are used, tapa is most commonly associated with paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera), or u‘a, a plant brought to the Moana from South-East Asia by early navigators.3 U‘a travelled into and across the Moana as cuttings; however, to date, it has not seeded in the region. Consequently, the u‘a used across the Moana share the same DNA, unified by a common ancestor plant.4

This is not to say that u‘a — and, by extension, tapa — has propagated identically across the region. While the plant may be the same, different environments have conditioned it — and the cloth it produces — in various ways. Types of tapa are distinguished by their soaking methods, the style of beaters used to flatten the fibres, and the stages of processing that can include fermentation or felting. Most visibly, tapa art forms also differ in their mark-making. Motifs and patterns vary from place to place, as does the mode of application: some practitioners apply pigment freehand, others use stencils, while others achieve large swathes of colour through a smoking technique. This diversity of creation is echoed in the multiple names for tapa. It is known as kapa in Hawai‘i, hiapo in Niue, siapo in Sāmoa, nemasitse in Ni-Vanuatu, ngatu in Tonga, masi in Fiji, uha in Rotuma, and aute in Aotearoa New Zealand, to name but a few.

The introduction of woven cloth, following the arrival of Europeans in the Moana from the late eighteenth century, had a huge influence on the trajectory of various tapa practices.5 In Sāmoa, Fiji and especially Tonga, siapo, masi and ngatu production never ceased; however, on other islands, tapa-making declined, although the possibility of makers unknown beyond their communities should not be discounted.

To relearn ‘sleeping’ modes of tapa, makers have followed several threads, from studying examples in museums to scouring journals recorded from historical field studies.6 The practical knowledge of how to harvest and process plants, however, is difficult to glean solely from studying museum objects or books. Acquiring hands-on, material knowledge has often necessitated learning directly from makers working in different versions of tapa. While it may seem counterintuitive to reinvigorate one type of tapa by learning from another, the survival rates of different practices have made it essential.

One tapa art form that has re-entered contemporary production is hiapo. Aotearoa-based, Māori-Niue artist Cora-Allan is arguably one of hiapo’s best-known living practitioners. Her research began with conversations with her grandparents and visits to local museums, and this visual analysis of hiapo and her grandmother’s knowledge of botanical species offered insight into patterning and mark-making. A lack of contact with living hiapo makers, however, forced Cora-Allan to conduct more research further afield.

Following an initial visit to Niue, Cora-Allan’s desire to learn hiapo led her to Sāmoa, where she connected with siapo-maker Fa‘apito Lesatele. In Sāmoa, Cora-Allan paid specific attention to Lesatele’s process of harvesting. Despite a UNESCO planting project targeted towards harvesting u‘a, Lesatele relied on groves located behind her house. From Lesatele, Cora-Allan learned the cloth-producing properties of different plants, as well as Samoan methods of ink-, soot- and glue-making. Cora-Allan directly borrowed and adapted some of these techniques, updating Lesatele’s method of collecting soot to include a funnel, which she later sent to Lesatele to thank her for sharing her wisdom.

Sharing knowledge, techniques and even materials across cultures is vital to reinvigorating tapa art forms. During the 1960s and 1970s, for example, many aspiring creators sought to relearn their own specific version of tapa-making. With few living kapa-makers available, travelling beyond Hawai‘i proved a common strategy. In the 1960s, Malia Solomon (1915–2005) journeyed to Sāmoa, Tonga, Fiji, and even Japan, to observe cloth-making, eventually sourcing wauke (the Ōlelo Hawai‘i name for u‘a) from Tonga to plant in Hawai‘i.7 In the 1970s, Puanani Van Dorpe (1933–2014) similarly travelled to learn from tapa-makers in Sāmoa and Fiji. More recently, kapa expert Wes Sen learned from Samoan siapo-maker Mary Jewett Pritchard (1905–92).8

The resurgence of kapa in Hawai‘i has in turn supported the resurgence of other tapa art forms. It was in Hawai‘i that Māori artist Nikau Hindin learnt techniques for making aute, the reo Māori term for both the u‘a plant and the barkcloth it produces. Until recently, knowledge about aute has been scarce. Though a small number of patu aute (kapa beaters) are held in the collection of the Auckland War Memorial Museum, and aute groves grow on the North Island, making aute has not been practised for at least a century.9

As part of an exchange at the University of Hawai‘i, Hindin encountered kapa-making with Lufi Matā’afa Luteru during a fibre-making class. Returning home to research aute, however, Hindin faced the challenge of not having access to living makers, so she planned subsequent visits to Hawai‘i to learn from kapa-makers Verna Apio-Takashima and Kaliko Spenser.

For Hindin, learning how to care for the wauke or aute plant was a significant takeaway from her time in Hawai‘i, as she notes:

. . . the most important thing to do is to plant the trees and to look after the trees because that affects the way the aute looks when you’ve beaten and processed it, so that’s one of the things that I really learnt in Hawai’i . . . the importance of harvesting and cultivating the plants.10

It is this knowledge of cultivation and harvesting practices that proves foundational to any tapa practice, and seeking out this information is vital in the wake of the plant’s scarcity. Anthropologist Andy Mills notes that the ‘increasing short supply [of paper mulberry] is one of the greatest obstacles to the renaissance of the art form everywhere’.11 As Cora-Allan reiterates: ‘Learning about hiapo through archives and research was fun; finding the plants, cultivating them, and making hiapo was the tricky part’.12

Travelling across waters and considering a range of tapa types and methods have been vital to overcoming these ‘tricky’ obstacles. Locating and cultivating plants is a lived practice, and seeking out living experts has revealed and, in effect, created transnational tapa networks. At times, these networks have been highly informal. Cora-Allan’s awareness of Lesatele as a siapo expert, for instance, came through a recommendation by an Auckland-based Cook Islands arts administrator. Even after returning to Aotearoa, Cora-Allan continued to meet with masi and ngatu makers. Each exchange revealed small nuances between the ‘juiciness’ of u‘a grown in different climates, and the qualities of the various hardwoods used to make beaters. Cora-Allan’s current practice is a distinct mix of elements specific to hiapo and influences taken from other tapa art forms, including a preference for using a Tahitian-style beater.13

At other times, institutional projects have deliberately established tapa networks. In 2023, a large gathering of tapa-makers took place in Tahiti. Led by Isaac Te Awa, a curator at Te Papa Tongarewa (Museum of New Zealand), and Pauline Reynolds, a tapa-maker, the Ahu-Ngā Wairua o Hina project brought makers from different tapa lineages and cultures together, including Cora-Allan, Nikau Hindin, Dalani Tanahy, Hinatea Colombani, Sarah Vaki, Liviana Qaranivalu, Tui Emma Gillies and Sulieti Fieme‘a Burrows, and Doron Semu. Each maker was asked to contribute six pieces, which were to be halved into two lots: one for Te Papa Tongarewa, in Te Whanganui-a-Tara (Wellington), and the other for Musée de Tahiti et des îles, in Puna’auia.14 The bundles replicated the pieces of tapa from a 1787 book by Alexander Shaw featuring samples collected during Captain Cook’s South Pacific voyages from 1768 to 1779.

Indeed, tapa’s long transnational history involves many pieces voyaging across the world in the hands of enthusiastic collectors. The Ahu-Ngā Wairua o Hina project of tapa ‘samplers’ suggests a different audience, one comprising makers working within and across the Moana. While Cora-Allan and Nikau Hindin are two well-known tapa-makers within Western art worlds, particularly in Aotearoa, projects like Ahu-Ngā Wairua o Hina acknowledge expert makers who are well-known within their own communities. The project not only documented different tapa types being made today, it also instigated lasting connections between the tapa-makers themselves.

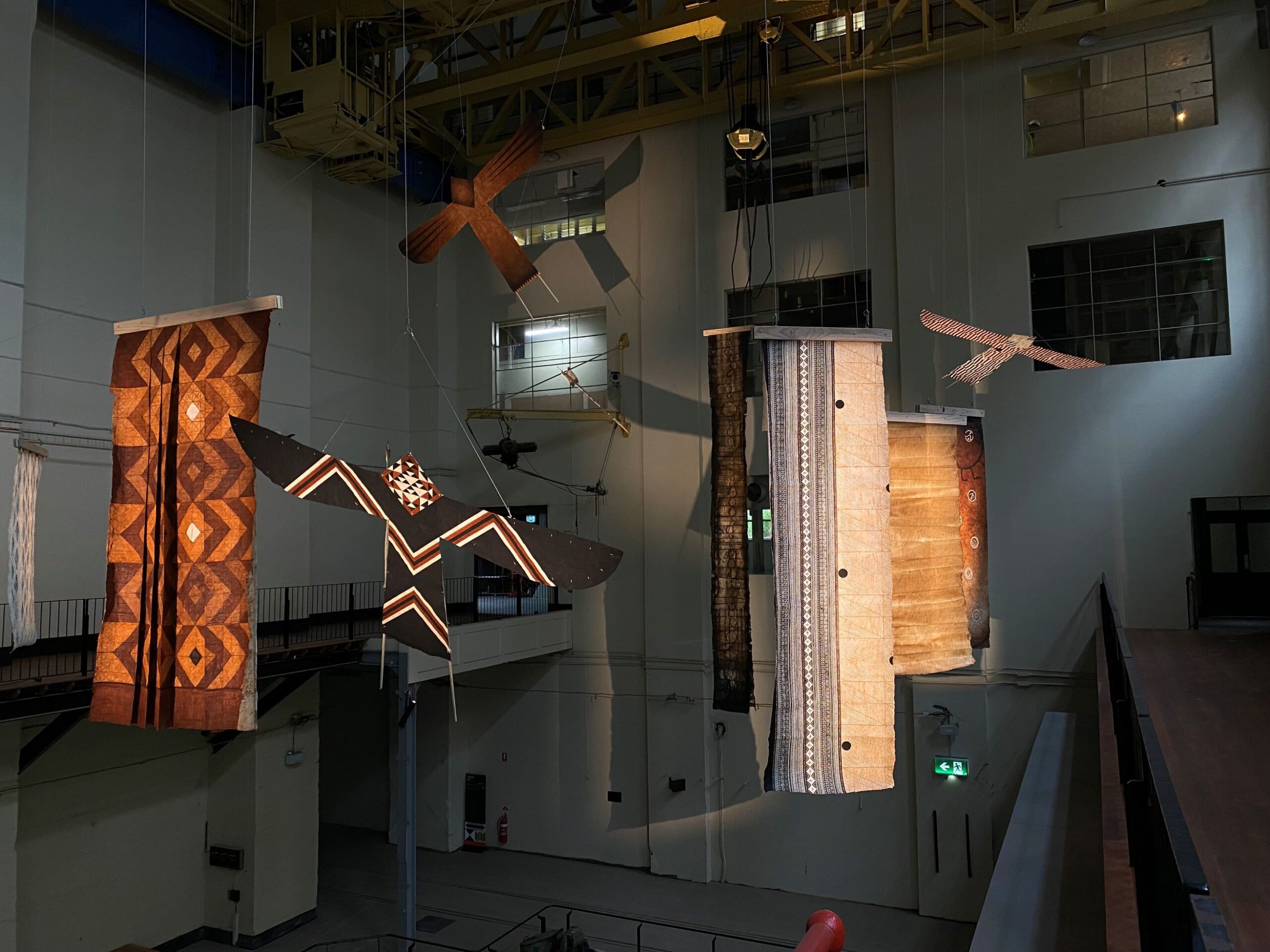

Nikau Hindin, Ebonie Fifita-Laufilitoga-Maka Fungamapitoa, Hina Puamohala Kneubuhl Kihalaupoe, Hinatea Colombani, Kesaia Biuvanua, Rongomai Grbic-Hoskins / Aumoana 2023–24 / Installation view, 24th Biennale of Sydney: Ten Thousand Suns, 2024, White Bay Power Station / Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney and the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain with generous support from Creative New Zealand / Courtesy: The artists and Biennale of Sydney / © Nikau Hindin, Ebonie Fifita-Laufilitoga-Maka Fungamapitoa, Hina Puamohala Kneubuhl Kihalaupoe, Hinatea Colombani, Kesaia Biuvanua, Rongomai Grbic-Hoskins / Photograph: Nikau Hindin

Nikau Hindin, Ebonie Fifita-Laufilitoga-Maka Fungamapitoa, Hina Puamohala Kneubuhl Kihalaupoe, Hinatea Colombani, Kesaia Biuvanua, Rongomai Grbic-Hoskins / Aumoana 2023–24 / Installation view, 24th Biennale of Sydney: Ten Thousand Suns, 2024, White Bay Power Station / Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney and the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain with generous support from Creative New Zealand / Courtesy: The artists and Biennale of Sydney / © Nikau Hindin, Ebonie Fifita-Laufilitoga-Maka Fungamapitoa, Hina Puamohala Kneubuhl Kihalaupoe, Hinatea Colombani, Kesaia Biuvanua, Rongomai Grbic-Hoskins / Photograph: Nikau HindinThere are many examples of similar exchanges. Most recently, the 24th Biennale of Sydney and Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain supported Hindin to lead an ambitious tapa collaboration. The resulting installation, Aumoana 2023–24 included work by tapa-makers Ebonie Fifita-Laufilitoga-Maka, Hina Puamohala Kneubuhl, Hinatea Colombani, Kesaia Biuvanua and Rongomai Grbic-Hoskins, as well as Hindin. Transnational and collective in nature, Aumoana featured five manu aute (Māori bird kites) and eight large-scale cloths by makers from five different nations and tapa-making traditions.

Interestingly, the Aumoana collaboration extended beyond the named makers. Four of the cloths — the Tahitian ‘ahu and Hawaiian kapa — were brought to Piritahi Marae, a community centre on Waiheke Island, in Aotearoa. There, a wider cohort of Māori artists adorned the cloth with kōkowai (red ochre pigment) and ngārahu (soot ink) that was gathered and processed in Hawai‘i and Aotearoa.

Learning about pigments — where to source them, how to process them, and how they seep into cloth — represents another stage in the resurgence of tapa. There is, in fact, an interesting trajectory from harvesting u‘a to harvesting pigments. In Hawai‘i, where kapa-making has been undergoing a process of regeneration for some 60 years, understanding plant dyes has today been deemed ‘[o]ne of the biggest challenges current practitioners face . . . in the manufacture of contemporary kapa’.15

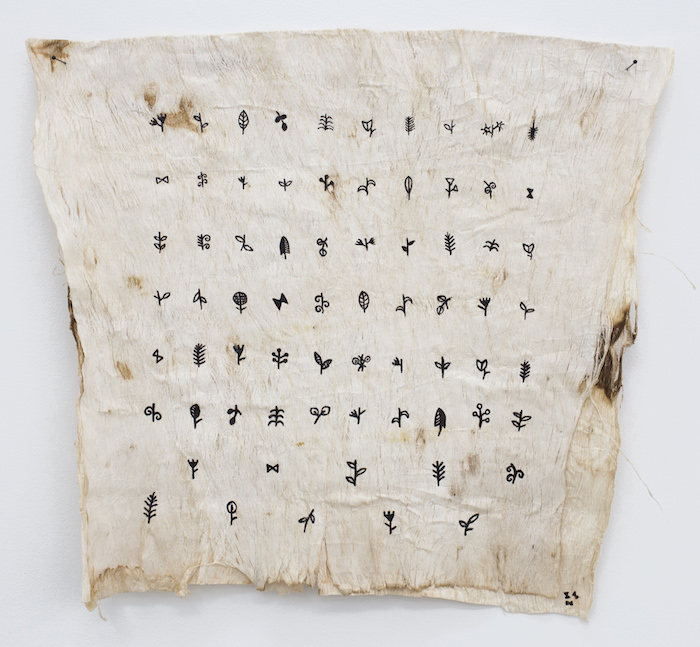

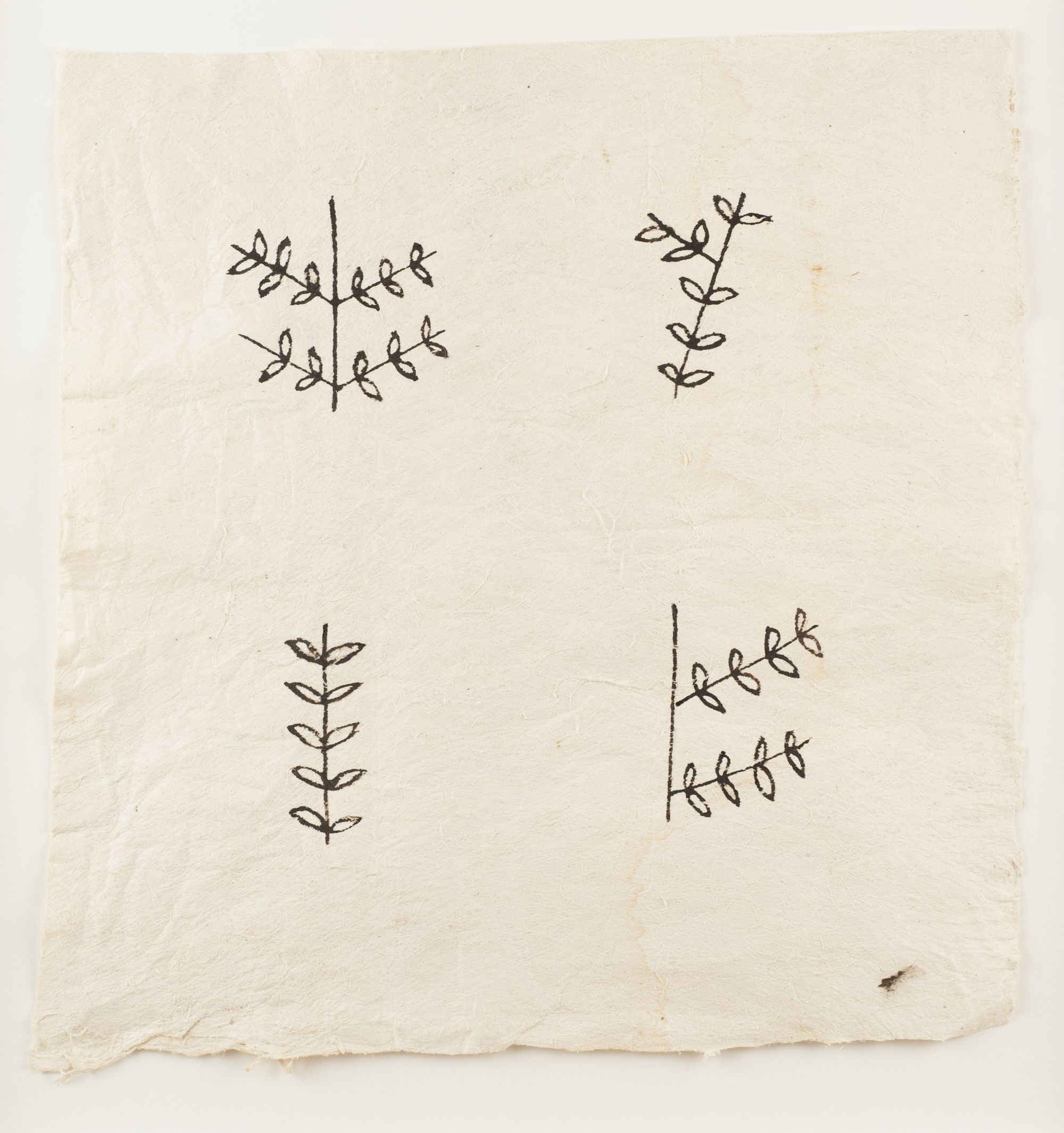

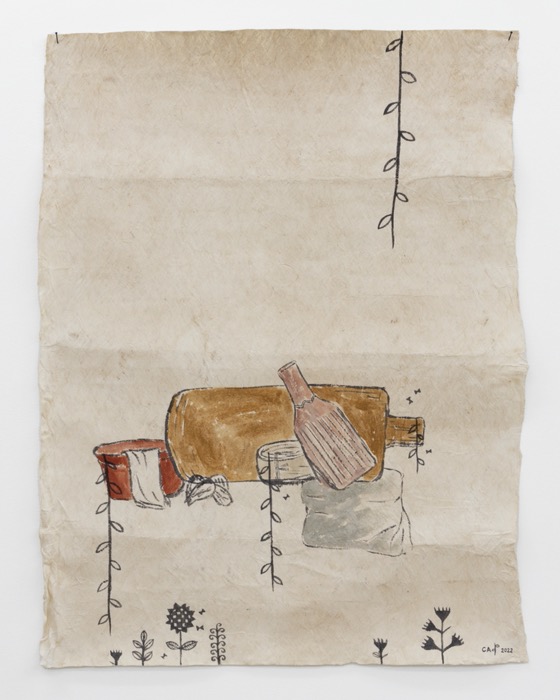

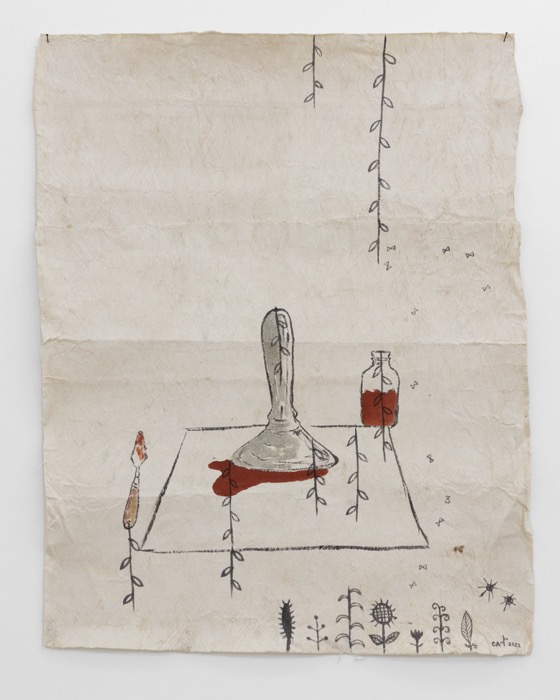

Pigment preparation is also a stage of the process when makers translate shared material knowledge into their own, specific tapa art forms. As previously noted, what most immediately distinguishes tapa types are their visual marks. Hiapo, for instance, is distinctive for its black palette on uncoloured cloth and its freehand imagery, featuring botanical forms. A significant thread of Cora-Allan’s practice has involved transcribing hiapo’s distinctive marks. In several works, including Flora and Fauna Sampler #1 2020 and Plant Sampler 7 2020, Cora-Allan records hiapo’s botanical imagery, while others, including Hiapo Sampler #2 2020, record hiapo’s geometric designs. Other works still, such as Gathering Whenua, Harvesting Whenua, Hiapo making tools, Hiapo tools and Whenua paint tools, all 2022, operate like visual production notes, each documenting the tools the artist uses in different stages of making and marking.

Aute, by contrast, is notable for a lack of extant decorated examples. With no references to adorned aute, Hindin draws on other art forms within Toi Māori (Māori knowledge), such as tukutuku (traditional latticework) and tāniko (traditional weaving). These Māori textile and architectural forms provide the foundation for Hindin’s visual system, which is based on celestial navigation and the Māori lunar calendar. Kuaka 2019 is but one example of Nikau’s star maps. The work marks star houses through niho taniwha (triangles) at the base of the piece that echo the silhouettes of maunga (mountains). Each fine, vertical line marks the declination of different stars on the horizon (where they rise), while horizontal lines along the edges mark the passing of time. The niho, or notches along the star lines, identify the stars and denotes the time they rise.

Hindin’s works also include multiple star maps, each indexed to a specific lunar cycle to demonstrate the way stars rise earlier and earlier every month. These celestial observations were traditionally used by Māori to track time and gather information for future weather events. The artist’s largest series to date, Ngā Whetū Maiangi o te Maramataka 2023, commissioned by the Bienal de São Paulo, includes 13 star maps and represents the stellar lunar calendar year between June 2022 and July 2023.

Nikau Hindin, Ngāpuhi/Te Rarawa/Ngai Tūpoto, Aotearoa, b.1991 / Rākau Nui 2023 (foreground) and Ngā Whetū Maiangi o te Maramataka 2023 / Installation view, 35th Bienal de São Paulo, Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, 2023 / Courtesy: The artist/Bienal de São Paulo / © Levi Fanan/Fundação Bienal de São Paulo

Nikau Hindin, Ngāpuhi/Te Rarawa/Ngai Tūpoto, Aotearoa, b.1991 / Rākau Nui 2023 (foreground) and Ngā Whetū Maiangi o te Maramataka 2023 / Installation view, 35th Bienal de São Paulo, Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, 2023 / Courtesy: The artist/Bienal de São Paulo / © Levi Fanan/Fundação Bienal de São PauloLike planting aute, reading the stars is dependent on following the natural cycles of time, and Hindin’s star maps record the movement of stars as they are observed in a time and place specific to Aotearoa. But, again, knowledge of how to observe the skies presents another example of transnational sharing. During Hindin’s time in Hawai‘i, she was immersed in the Polynesian Voyaging Society’s continuing efforts to reinvigorate customary voyaging and navigation.16 Navigators use the position of stars to determine direction; every star rises from a certain star house and returns to this house in the west after travelling across the sky. In the absence of knowing how aute was marked, it is this knowledge of navigation that in part informs the artist’s visual language.

Even when seeking to record or develop specific cultural marks, there is often a transnational inflection. Transnational influences over tapa styles, however, are hardly new. Cora-Allan’s travels to Sāmoa, for instance, echo earlier entanglements between hiapo and siapo. During the nineteenth century, Samoan missionaries introduced tiputa, a poncho-like tapa garment (itself introduced to Sāmoa by Tahitian missionaries) to Niue.17 There is also research on the influence of Samoan siapo on hiapo, and most notably a similarity between the freehand style of Niue hiapo and a style found in Sāmoa, called siapo mamanu.

Cross-cultural stylistic exchanges are still seen in contemporary collaborations. One work in the ambitious installation Aumoana 2023–24 was Matua, a collaboration between Ebonie Fifita-Laufilitoga-Maka and Kesaia Biuvanua.18 Matua combines fine stencilling, a technique well known in Moce in Fiji, where Biuvanua grew up, with rubbed kupesi, a method closely associated with Tonga and Fifita-Laufilitoga-Maka’s own ngatu art form.19 In addition to combining mark-making processes across Tongan and Fijian tapa idioms, the work echoed earlier moments of tapa exchange. Tonga and Fiji have a long history of tapa crossover, which is perhaps most visible in the Lau islands in Fiji, where a Tongan-style rubbing technique is often used on masi. Matua also echoes more recent transnational collaborations between Fifita-Laufilitoga-Maka, Māori artist Robin White, ngatu-maker Ruha Fifita (Fifita-Laufilitoga-Maka’s sister) and masi-maker Tamari Cabeikanacea (Biuvanua’s mother).20

The continuous exchange between tapa art forms and makers perhaps blurs what is unique to each, and what is shared or adoptable, particularly when transnational lessons are so vital to regaining material knowledge. Situating a tapa practice is consequently often defined by its makers. For Cora-Allan, the origin of the plant she uses is vital to positioning her practice as hiapo. Though she has worked with plants in Aotearoa, many of her materials come from Niue. In addition to candlenut and mangrove trees used for inks, Cora-Allan brings partially processed, dried u‘a strips back from her regular visits to Niue; she then re-soaks and re-beats them in Aotearoa. For the artist, importing plant material maintains her connection to hiapo. Living in Aotearoa and having Māori lineage means her practice could quickly become aligned with aute, rather than hiapo, as she has remarked: ‘If I’m using plants from here, they become aute. But if I’m using material from Niue or the Pacific, they’re hiapo. For myself, I make hiapo’.21

Recently, Cora-Allan has introduced whenua (earth) pigments from Aotearoa to her hiapo. On the inside border of Hiapo Toi 2021 is a series of triangles that alternate in orientation, in a pattern echoed and amplified by their colouring. All the triangles pointing inwards have been in-filled with smaller, black-outlined triangles. The triangles pointing outwards alternate between uncoloured shapes and those coloured with pukepoto. A distinctly blue addition to the traditionally black and unmarked hiapo, pukepoto is a pigment made from whenua (earth), and in the case of Hiapo Toi, sourced in Aotearoa. Highly sought after and incredibly scarce, pukepoto is the lapis lazuli of the Moana.

Adding whenua pigments from Aotearoa to hiapo combines a Niue art form with Māori materials and techniques, and reflects Cora-Allan’s Māori and Niue heritage. This deliberate blend is highlighted in the work’s title, Hiapo Toi, which is a vagahau Niue word for ‘cloth’, followed by the te reo Māori term for ‘art’. Hiapo Toi exemplifies this cross-cultural exchange, where different cultures, contexts and conditions combine to create something new. Cora-Allan’s recent artworks are not simply hiapo, nor are they aute — they are hiapo toi, a form of hiapo uniquely characterised by its production in Aotearoa and the Māori–Niue heritage of their maker.

While Fifita-Laufilitoga-Maka and Biuvanua’s Matua and Cora-Allan’s Hiapo Toi may align with an image of ‘transnational tapa’, a closer look at the resurgence of tapa reveals another layer to the art form’s dynamic. Makers often travel across oceans and cultures to learn from each other, specifically seeking knowledge of the ecologies and cycles of planting, harvesting and processing. Just as u‘a plants have only been propagated through cuttings that travel, the resurgence of tapa often begins with learning the fundamentals of material processes from other places.

Ultimately, tapa takes root in an artist’s practice by being shaped to the individual’s unique cultural context and their own specific experiences of cross-cultural exchange. Herein lies the fascinating paradox of tapa — recovering unique versions of tapa often relies on cross-cultural travels to learn from seasoned makers, and it is these exchanges that then ensure the diversity of tapa. Where exactly an individual artist’s practice may fall within this matrix ensures that tapa is always a living art form, always dynamic. But to find your place within tapa’s ocean currents and star maps, you must first learn from a maker in person.

This paper has been supported by Creative New Zealand, the Arts Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa.