Gunybi Ganambarr / Ngaymil people / Australia b.1973 / Macassan sail 2020 / Stitched boat canopy and work shirt, wooden turtle-hunting harpoons / 233 x 400cm / © Gunybi Ganambarr / Courtesy: Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

Gunybi Ganambarr / Ngaymil people / Australia b.1973 / Macassan sail 2020 / Stitched boat canopy and work shirt, wooden turtle-hunting harpoons / 233 x 400cm / © Gunybi Ganambarr / Courtesy: Buku-Larrnggay Mulka CentreIn the long world history of seafaring, some voyages from the Northern to the Southern Hemisphere stopped at the equator — with the journeys transforming into colonialism. The same happened with trips from the Western world to the Eastern. Other trips, from equatorial regions to the southern part of the world, including to Australia, are much less talked about. Although the distance travelled was shorter, the history and legacy of these trips is astounding.

The voyage from the equatorial region to a new continent untouched by the whites was started by Makassar sailors in search of sea cucumbers. The sailing trips — as recorded in notes written by Campbell McKnight in The Voyage to Marege’: Macassan Trepangers in Northern Australia (1976) — lasted about 250 years, from the early seventeenth to the early twentieth century. However, artefacts suggest these cruises may have continued for even longer: for example, the image left in the paintings of prehistoric caves in South Sulawesi and northern Australia. In addition, the words ‘Makassar’, ‘Macassan’ and ‘Mangathara’ refer to the sailors and the place. The sailors called Macassar people are usually from Bugis, Makassar, Malay, or even Jawa ethnicities. This sailing route is important in the maritime history and cultural heritage of Indonesia and Australia.

The route was initiated by the needs of Asian people, especially the Chinese, for sea animals named trepang, or bêche-de-mer, or sea cucumbers — for medicinal purposes and food. The port of Makassar, in the Kingdom of Gowa, was the centre of this market, and the traffic of merchant ships covered almost the entire archipelago: South-East Asia (Singapore, Philippines, Malaysia) to northern Australia via the Arafura Sea, through the province of East Nusa Tenggara to the different places in the Northern Territory, including Darwin, Elcho Island, the Kimberley and ending in Yirrkala, on the north coast of Australia.

If not for this trade in the past, perhaps we would not have had the long history of cultural assimilation and mixed marriages that has produced the complex and rich lineages in this region. Moreover, the richness of Macassan language and art forms is still very well and majestically preserved by the Yolŋu people of Northern Australia.

In 1986, it was noted in the Harian Pedoman Rakyat, one of the local newspapers in Ujung Pandang (the old name of Makassar), that a group of residents from Marege (the Makassar name for Australia and Australian Aborigines) attracted the attention of Makassar people. The meeting was attended by a dozen people in the family home of Husain Daeng Rangka, the legendary Macassan sailor known by the Yolŋu people as Utjing or Using. Tears of joy and happiness flowed during the exchange. The group from Marege were given Northern Territory experiences: eating with their hands on the floor of the house; seeing old palm trees; and visiting a prehistoric cave site containing images of humans hunting animals and boats. On that occasion, they met the family and grandson of Utjing, as well as an old woman of Aboriginal origin who was the last Aboriginal resident in Makassar. The meeting was like reviving a relationship that had been stalled for decades — since 1907, when the South Australian Government began to apply taxes to and require sailing permits for the traditional sea voyage. The seafaring tradition that had lasted for centuries stopped, and the relationship between the two societies was severed.

It was a heavy blow to both the north Australians and the Makassarese. This was a matter of breaking up not only trade and sailing affairs for sea cucumbers, but also family relations that had lasted for centuries. In deep sorrow, the Yolŋu people record their memories of the event in dances and songs which they call Djapana (which sounds similar to the Makassar word djappama, which means, ‘I’m leaving’, or ‘I left first’).

Various efforts were made to retain the memory of this trade route for the next generation. Songs, dances, paintings and mantras are well preserved in practices and everyday language of the Yolŋu people. Both tangible and intangible objects — such as weapons, languages, boats, pictures, flags, beaches, tamarind trees, coconut trees, palm trees, colourful paintings — became an important part of the remembered legacy between the two cultures.

As far as I know, there is almost no other culture in the world that is so large, so strong and deep in retaining knowledge of the Indonesian heritage that has been passed down from generation to generation — outside the Indonesian entity itself — than the Yolŋu. I may be exaggerating, but it is too good to be true. Some of my experiences seem to confirm this.

In 2014, when the Australian Embassy in Jakarta brought the late, legendary Australian musician Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu to an annual music event in Jakarta and Makassar, he had the opportunity to visit Rumata Art Space, where I used to work as director for programs and development. At that time, Gurrumul’s team visited with their manager and producer Rama Thaharani, Ali Donnellan as well as Allison Purnell from the Australian Embassy. Before they returned to Australia, I had the opportunity to help arrange a short tour for Gurrumul and his team, visiting several points in the city of Makassar, especially the coastal area (I cannot imagine how excited and happy Gurrumul felt; even though he was visually impaired, he could definitely feel it. He got to experience the atmosphere of the city where his ancestors came from). This visit was beyond any dimension I could have imagined.

When Paul Grigson’s tenure as Australian Ambassador to Indonesia in Jakarta was coming to an end in 2014, he initiated the Yirrkala Batik Project where several pieces of written batik were ordered and specially produced with the legendary artist from Yirrkala, Nawurapu Wunuŋmurra. Mr Nawurapu’s bark paintings were transferred to the form of written batik cloth made by Pekalongan batik makers. Mr Nawurapu’s family is descended from Makassar sailors in Yirrkala, and his paintings are about fish and sails of prau, based on his memories of the stories, passed down through generations by his grandfather, about his people’s relationship with Makassar sailors. The Yirrkala Batik Project involved me as implementing coordinator for Makassar. At that time, I felt like I was in love with Yirrkala. It was like a lost relationship had been rebuilt. I feel there is a different energy that makes me want to go on longer and longer journeys. I can still feel the vibrations of that energy today.

In July 2015, we held an event for the Yirrkala Batik Project in Makassar as part of the celebration of NAIDOC Week. It was marked by a signing inauguration and an opening by the Australian Consulate-General office in Makassar. Symbolically, Yirrkala batik has now become a part of Makassan life through the Museum of the City of Makassar. We are happy that the museum maintains a special room for the collection of traces of Australia–Indonesia relations through the sea cucumber trade. The batik cloth is still beautifully displayed in this museum.

In the same month, it was like fate brought me together with the living legend, Nawurapu Wunuŋmurra; curator of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala, Will Stubbs; and Jamie Wakarriny Wunuŋmurra, a young Yolŋu artist who is Nawurapu’s grandson. Meeting them felt like a gift, a kind of reconnection. There is a special feeling I have about that event. A feeling that goes beyond the satisfaction of managing an artist’s program or meeting with other artists.

Before leaving for Yirrkala, the four of us — Mr Nawurapu, Will, Jimmy and me — exchanged things (as our ancestors did). Mr Nawurapu gave me a fish-shaped wooden carving, while I gave him some earthenware — a small gumbang or bempa (waterpot) I had collected from the backyard. The exchange took place at dusk, accompanied by singing and the rhythms of Sinrilik (a stringed instrument from Makassar), as well as yidaki (didgeridoo) and Yolŋu songs with the rhythm of clicking sticks. We will meet again — those words resonate in my head because it was how I felt when their car left for the airport. A month later, Will sent me a photo of the water pot I had given him, which Nawurapu had now painted. Inside there were images of a cigarette, tobacco pipe, cloth, pants, work tools and a sailboat. All of them are memories of Makassar people. At that moment, I said to Will, ‘We have to do something with this’. I replied to his email with a picture of pottery by a classic Makassar pottery craftsman who still survives from Soreang village.

Less than a year after that meeting, in 2016, it was as if the universe had heard my dream. Like the North Wind blowing up the South, the Australia Council for the Arts invited me as one of the Indonesian delegates to the Australian Performing Arts Market in Brisbane. During the week, I met many people from various backgrounds in the Queensland arts hub. One day, I used my time off to visit interesting sites, buildings and local museums. I spent two hours at QAGOMA, viewing ‘The 8th Asia Pacific Triennal of Contemporary Art’ (APT8). My thoughts and feelings were really excited at that time — I trembled and shuddered. I tried to calm myself down. I sat for a long time on the ground floor of the building. While touching one of the works, I slowly whispered to myself, How beautiful and happy would it be if your work was displayed here too, Abdi. I rushed to the counter, purchasing an exhibition program as a memento.

Before leaving for Indonesia, I stopped for a few days at Yirrkala. Will Stubbs and his family had arranged everything. From Darwin, I took a propeller plane to Yirrkala. The airtrip left me in awe, staring at the river that winds along the northern coast of Australia. In an instant, my memory flashed to the story of the Rainbow Serpents and the bark carvings. Arriving at Yirrkala, I was immediately greeted like a family member who had just returned home from wandering. Everyone shouted, ‘Mangathara!’, or ‘Macassan!’ I felt like I was at home. Will’s wife, Merrkiyawuy Ganambarr, and their daughter, Siena Ganambarr-Stubbs, gave me a very warm welcome.

In Yirrkala, the universe never stops surprising me, and it doesn’t stop surprising Will and his family. That morning, we walked along several beaches in the East Arnhem Land area and ended up in Bawaka. We hunted fish with spears. I really don’t have any fishing experience, let alone fish-hunting experience. But somehow, my first spear hit a medium-sized spotted stingray. At once, Mamla (‘Mother’ in Yolŋu — my name for Merrkiyawuy Ganammbarr) called Will and asked him to take off the stingray’s tail pricker. With eyes wide open, Will said, ‘As far as I remember, even the local people almost never got a fish on the first throw. Perhaps this is because the sea spirit recognises and greets us’. I just smiled proudly because Mamla would cook the fish we caught for dinner.

On the shores of Bawaka beach we gathered while preparing dinner. Not long afterwards, five big men came over. Apparently, they were clan leaders in the area who were also relatives of Mamla Merrkiyawuy. One of them, Timmy Djawa Burarrwanga, was surprised to see me, and flabbergasted when Will introduced me: ‘This guy is Mangathara!’ Timmy shouted, ‘After a long time, finally a Mangathara is back here!’ Will had previously told me when he picked me up at Nhulunbuy Airport that my arrival would surprise the locals, because I was the first Macassan to come to Yirrkala in a long time. Such a long time.

Timmy pulled my arm and invited me to sit around the bonfire. We shared stories and played guessing the nouns for things around us in our respective languages — galuku-kaluku (coconut), balay balay-bale bale (shelter), lipa-lipa or lepa-lepa (canoe), and many other fun quizzes. When Mamla and Will told them about the stingray on my first pitch, Timmy’s face immediately changed. He came closer while whispering something in my ear. I suspect it was a sacred or special spell because he didn’t want his other siblings to hear it. Even though it was low and faint, I could recognise some words: Alla for Allah; Hamma’ for Muhammad; and Bayini for Baine (women in Bugis-Makassar).

How can a culture that is outside its religious and cultural entities retain such memories through sacred spells? Timmy then called me Wawa, which means brother — it was a kind of baptism for me — and later gave me a special name, Goŋu. That name means the part of the coral on the beach that holds water, and is the name of the type of stingray that is a symbol of knowledge and one of the clans in Yirrkala. Since then, I have officially become part of their big family. And, since then, when I go to Yirrkala, surely, it is like I am back home!

This kind of rare event may only occur once in a lifetime: like Makassar sailors returning to Australia’s north; walking along the coast looking for pottery shards; the red sunset; eating fish near the tamarind tree; gazing at the saltwater crocodiles; hearing the story of Bayini — guardian spirit of the island; to hear the strains of yidaki and singing when invisible dingos howl near us, it feels supernatural. I felt this random energy in my hometown when a sacred event occurred. The nature and scene gave me a different vibration. Even when my plane took off from the airport, I felt like I was in a padewakang boat piercing the horizon of the northern coast of Australia, waving and listening to Djapana … Djapana.

In 2017, Will Stubbs and I initiated an exhibition titled ‘Budjung’. In the Yolŋu and Bugis-Makassarese languages, budjung is a word for a water container, or well. This exhibition presented a number of Macassan pots specially made by artisans in Soreang village, then sent to Yirrkala, where they were painted by the legendary Yolŋu artists: Djakaŋu Yunupiŋu, Djalinda Yunupiŋu, Mulkun Wirrpanda and Nawurapu Wunuŋmurra. The exhibition is a meeting of two different classical traditions in one object, presenting different dialogues: Makassar’s classical pottery tradition combined with sacred Yolŋu painting offers a different dimension and contemporary notion of the centuries-old relationship between the two cultures. With the support of Richard Matthews and Violet Rish from the Australian Embassy and Consulate-General of Australia in Makassar, the exhibition also presented a series of bark carving replicas of Old Masters from the collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. The ‘Budjung’ exhibition adds to the short list of efforts to reconnect relations between the two countries: the Hati Marege ship expedition in 1986; the return visit of a group of Gowa artists to Elcho Island in 1992; the collaborative theatre production The Eyes of Marege at the OzAsia Festival in 2007; and the expedition of Pelayaran Akademik II in a sandeq boat in 2011. The interesting part is, all of these events have been citizens’ initiatives undertaken in the context of art and culture.

When I was invited to participate in ‘The 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT10), I really felt that the universe was listening to my voice and making my dreams come true. Through a number of specially crafted pots, I experienced several emotional episodes that I cannot explain. For example, when I discovered that the pottery artisan in Kampung Soreang, in Takalar Regency — located approximately 48 kilometres south of Makassar — who specialised in large cooking pots had died, and his children and neighbours no longer had the exact same pottery-making skills, for me, a chain of knowledge was lost. Immediately, the large cooking pot in the hands of the Yirrkala residents, stored in the Buku-Larrngay Mulka Centre, became an important object in the inheritance of these memories.

As a solution to this lack of knowledge and skills, I presented a replica of a similar pot with the help of artisans from Kasongan, a pottery village in southern Yogyakarta. I see this process as similar to how sea-cucumber hunters divide their work, based on their respective knowledge and skills. Sometimes, the composition could be like this: the ship’s owner is Bugis; the captain is Makassarese; the captain is Bajo; and the crew is Javanese. Diversity of ethnic backgrounds and ages is common in the seafaring tradition. We have pottery containers of water, and cooking pots in several sizes, and also a water bottle on display in APT10. This bottle imitates the shape of the bottle left by Makassar sailors collected by the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory.

The Yoluŋu/Macassan Project in APT10 especially presents karoroq or tanjaq — sails woven from the leaves of the arrenga pinata or gebang tree, from the palm plant family. Traditionally, metres of rope made from coconut fibre braided and hand-woven with palm tree fronds was used for everyday and sailing needs, and in the building of houses.

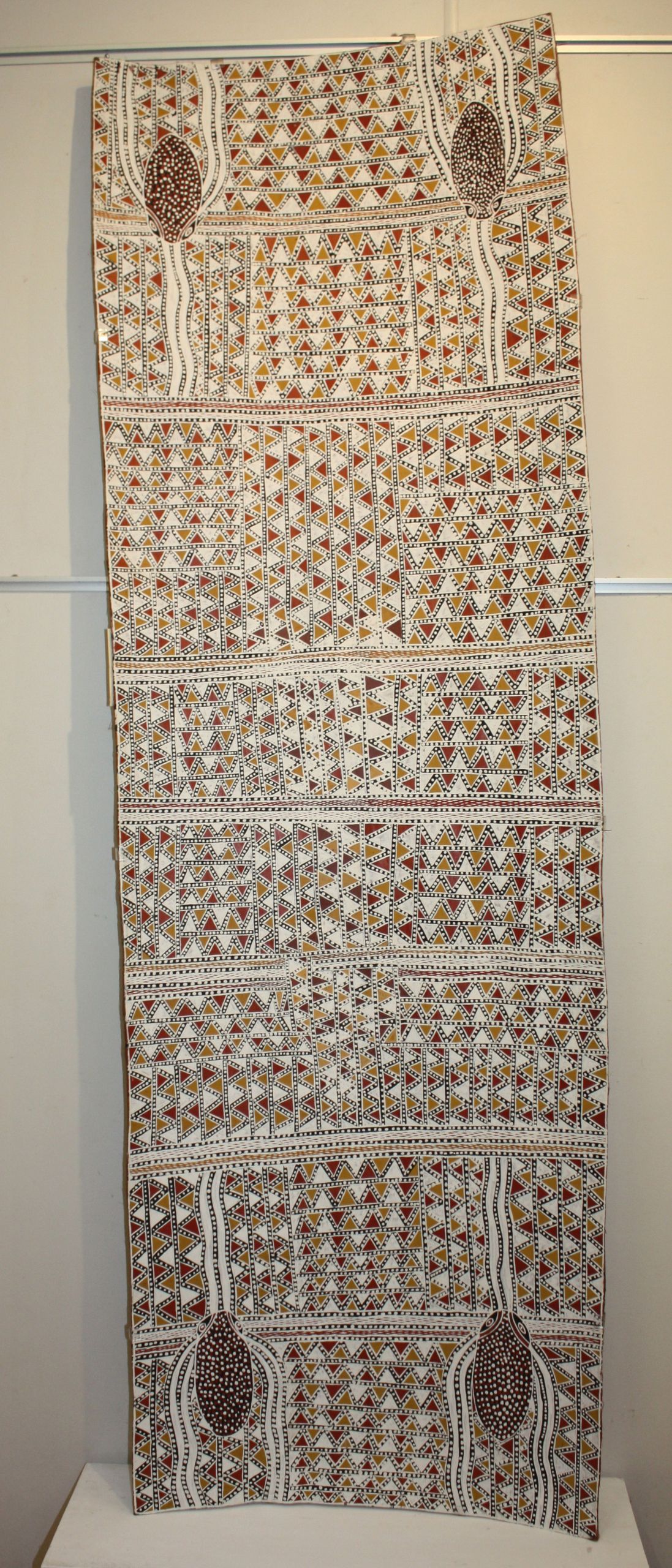

Munggurruwuy Yunupingu / Gumatj people / Australia b.c.1907 d.1978 / Macassan Praus c.1958 / Natural pigments on eucalyptus bark / 110 x 72cm / Gift of Robert Bleakley through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation 2020. Donated through the Australian Government's Cultural Gifts Program / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Munggurruwuy Yunupingu

Munggurruwuy Yunupingu / Gumatj people / Australia b.c.1907 d.1978 / Macassan Praus c.1958 / Natural pigments on eucalyptus bark / 110 x 72cm / Gift of Robert Bleakley through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation 2020. Donated through the Australian Government's Cultural Gifts Program / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Munggurruwuy YunupinguThe bark painting of Dhuwarrwarr Marika is also special: it is transposed onto a piece of batik cloth made in the traditional way using natural dyes. The images of machetes and keris tools in Dhuwarrwarr’s paintings are incarnated in batik cloth, as if to emphasise that knowledge, memory and information of what has happened in the past will continue to be present, move and change medium, through their own ways. And we as humans can take small initiatives to maintain it. Thus, we never really lose memory of the past, and have hope for the future.