Essay

India’s Adivasi artists and ‘Other Masters’: Confronting the establishment for an evolving contemporary

Djambawa Marawili, Jangarh Singh Shyam, Liyawaday (Kathy) Wirrpanda), Lado Bai / [Untitled] 1999 / Synthetic polymer paint on canvas / 182 x 500cm / Collection: Crafts Museum, New Delhi / Photograph: Laxman Das Arya / Image courtesy: RMIT Gallery, Melbourne / © The artists

Djambawa Marawili, Jangarh Singh Shyam, Liyawaday (Kathy) Wirrpanda), Lado Bai / [Untitled] 1999 / Synthetic polymer paint on canvas / 182 x 500cm / Collection: Crafts Museum, New Delhi / Photograph: Laxman Das Arya / Image courtesy: RMIT Gallery, Melbourne / © The artistsA series of contentious yet highly influential events took place in India in the 1980s and 1990s, at a time when institutional and industry hegemonies had all but effaced indigenous and so-called ‘folk’ art from the discourses of modern and contemporary art. A small group of artists — who would come to be considered pioneers in transforming hereditary and community-driven art practices into new formats for new audiences at a time of burgeoning international interest in Indian art — were recognised by two distinct initiatives. Artist Jagdish Swaminathan orchestrated a research project in contact with some of India’s indigenous and regional communities in the early 1980s, to develop a collection for the new Bharat Bhavan arts complex in Bhopal. The venture sought the work of practising artists who had been largely overlooked by the contemporary art industry for an exhibition at Bharat Bhavan’s Roopanker Museum of Fine Arts. Swaminathan’s project led to the 1987 exhibition ‘Perceiving Fingers’, which provocatively exhibited contemporary ‘urban’ and ‘non-urban’ artists on an egalitarian platform. In 1998, Dr Jyotindra Jain, Director of the National Crafts Museum in Delhi since 1984, took another significant step in positioning India’s indigenous and folk artists within a contemporary discursive framework for his exhibition ‘Other Masters’. Jain forthrightly challenged the anonymous and static perception of regional artists that had denied their contemporaneity and, in doing so, as cultural theorist Nancy Adajania described, he ‘theorised and re-historicised expressions long unacknowledged either as “contemporary” or as “art” by the cognoscenti’.1

Though some of the institutional prejudice and myopic perspectives of India’s arts establishment persist, these early initiatives set an important precedent, and continue to influence contemporary platforms as Indian indigenous (commonly known as Adivasi or ‘first inhabitants’ in South Asian) and so called ‘folk artists’ forge new pathways, in India and around the world.

Constructing platforms

Over the past decade several exhibitions have drawn attention to the hierarchical barriers involved in contemporary art on highly prominent platforms in India. These events have reignited provocations made decades earlier for shifting contexts, while continuing to grapple with defining suitable positions for practices that are considered outside the contemporary canon. The late Pardhan-Gond artist Jangarh Singh Shyam — the pioneer of the erroneously titled ‘Gond art’ (the bards and musicians were previously referred to by their Pardhan caste, with the Gonds being their patrons) who was famously encouraged by Jagdish Swaminathan to leave his village and begin working on paper — was finally recognised at a major Indian museum when the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA) held ‘Jangarh Singh Shyam: A Conjuror’s Archive’ in 2018.

Curated by Dr Jyotindra Jain and KNMA’s Director and Chief Curator, Roobina Karode, the exhibition extended the premise of Jain’s ‘Other Masters’ to the present era, staging a retrospective of the (relatively recently) celebrated master artist at the foremost private contemporary art museum in India. The extensive survey also featured Shyam’s many family collaborators and peers, conveying the importance of his career for his community.

At Devi Art Foundation in 2011, ‘Vernacular, in the Contemporary’ presented a major exhibition focusing on the work of artists working at the time. Led by designer and art historian Annapurna Garimella, the exhibition signalled another important moment in bringing indigenous and folk practices into a prominent setting for contemporary practice. Rather than imposing determined, binary categorisations, Garimella framed the exhibition in terms of ‘the vernacular’ relative to the processes and conversations of working with the artists, which enabled the curators the ability to speak about the work of the artists without depending on the familiar terms of ‘folk’ and ‘tribal’.2 Teams of researchers conducted regional travel to ‘focus on material conditions of art-making’, driven by a rethinking of pedagogical frameworks, in a deliberate attempt to create a necessary change in the exhibition model.3 Garimella’s responsive fieldwork approach resonated with Swaminathan’s method of seeking encounters with artists in the homes and villages of Madhya Pradesh decades earlier. For Garimella, there was little apparent intent in placing the exhibition’s participants in the same critical realm as some of India’s better-known contemporary artists; however, the project was enabled by Anupam and Lekha Poddar’s diverse collecting interests and experimental commissioning in building the Devi Art Foundation collection. Art historian Katherine Hacker has equated the project with Swaminathan’s transformative collecting and commissioning for Bharat Bhavan.4

Jyotindra Jain in conversation with Annapurna Garimella on the mediated demarcations between folk art and modern art, Mumbai, 7 March 2019 / Image courtesy: Asia Society / For the full conversation, see 'A Conjurer's Archive and Art Historical Divides': https://asiasociety.org/video/conjurers-archive-and-art-historical-divides-complete/

Jyotindra Jain in conversation with Annapurna Garimella on the mediated demarcations between folk art and modern art, Mumbai, 7 March 2019 / Image courtesy: Asia Society / For the full conversation, see 'A Conjurer's Archive and Art Historical Divides': https://asiasociety.org/video/conjurers-archive-and-art-historical-divides-complete/In early 2020, author, publisher and commentator on Dalit rights S Anand staged another experimental venture into the Devi Art Foundation’s collection with the exhibition ‘Suññatā Samānta: Emptiness Equality’. Presented at a warehouse a short distance from the concurrent India Art Fair, Anand included indigenous works from the collection along with work by authors, poets, amateur artists, local labourers and well-known Indian, Pakistani and international artists. An experimental exhibition, presented without exhibition labels to identify the works, ‘Suññata Samānta’ was a deliberately provocative gesture exploring how a hierarchy is applied to the idea of contemporary art.

While Anand’s approach differed from Garimella’s and posed further questions about the art market and institutional conventions, both curators positioned indigenous and folk art in frameworks that acknowledged a broader interpretation of contemporary art in India and a shortcoming of conventional exhibition models.

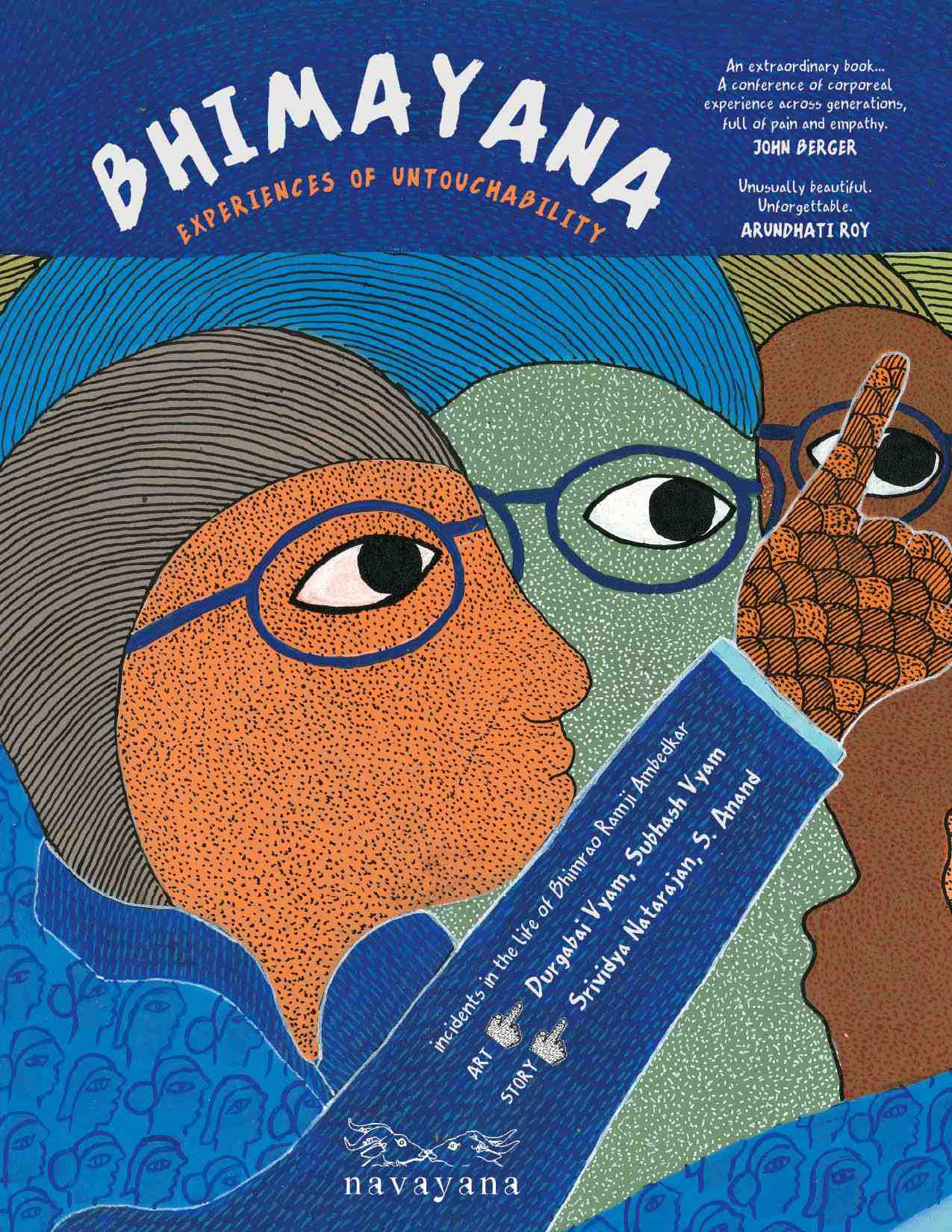

Anand’s close association with Gond artists stemmed from his publishing house, Navayana, which focuses on issues of caste. Through publishing, he has provided a platform for indigenous artists to narrate their own stories and perspectives. A notable example is the graphic biography of BR Ambedkar, the Dalit reformer and architect of India’s Constitution, presented in Bhimayana: Incidents in the Life of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar 2011, which is illustrated by Gond couple Durgabai and Subhash Vyam.

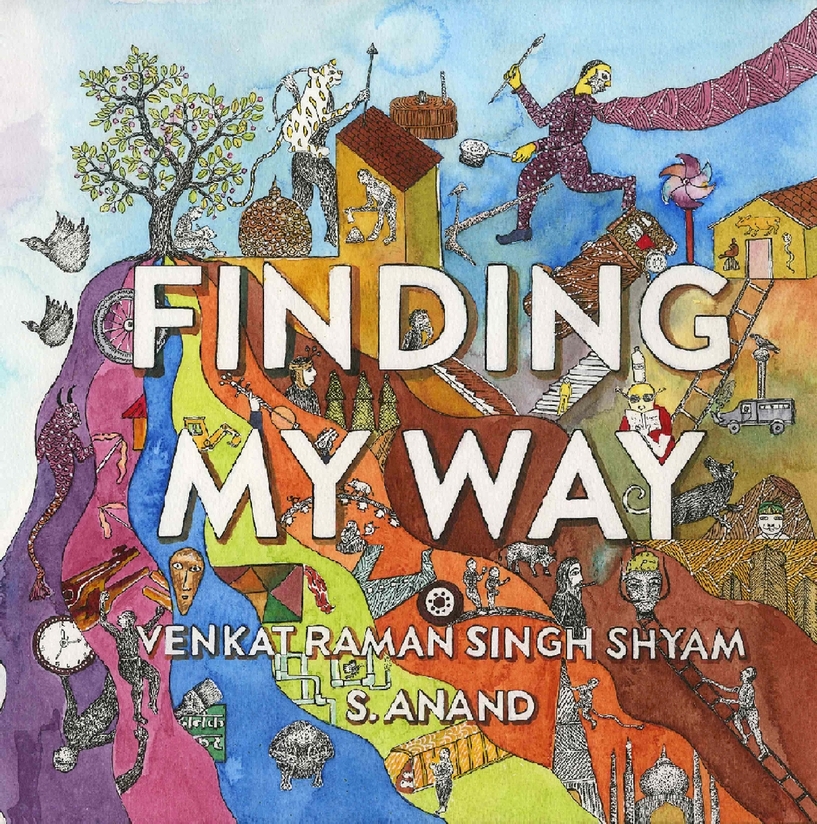

The book, translated into several Indian and foreign languages and now part of the syllabus in thousands of Indian schools,5 has taken the visual narrative provided by the Vyams, who have been described as illiterate, further than could have been imagined. This success inspired fellow artist Venkat Raman Singh Shyam to approach Anand to publish his own story, which resulted in the semi-autobiographical Finding My Way — a rare example of an art-related publication by an indigenous person, described by the artist as ‘a story of not just me and my art, it is the story of the Pardhan Gonds, who chronicled time and memory with their songs and music’.6 Poignantly, the book begins with a tribute to Jangarh Singh Shyam.

In a rare example in India, of indigenous art reaching a global audience, Durgabai and Subhash Vyam were invited to participate in the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2018–19, India’s most prominent international contemporary art exhibition. At the main venue of Aspinwall House in Fort Kochi, the first room visitors entered was an immersive world of paintings by the Gond couple. The 2018 edition of the Biennale deliberately foregrounded artists outside the mainstream, inspired by the impulse of curator Anita Dube, who specifically sought to ‘look at the margins’, highlighting practices by women and Dalit artists and challenging some of the extant power structures.7

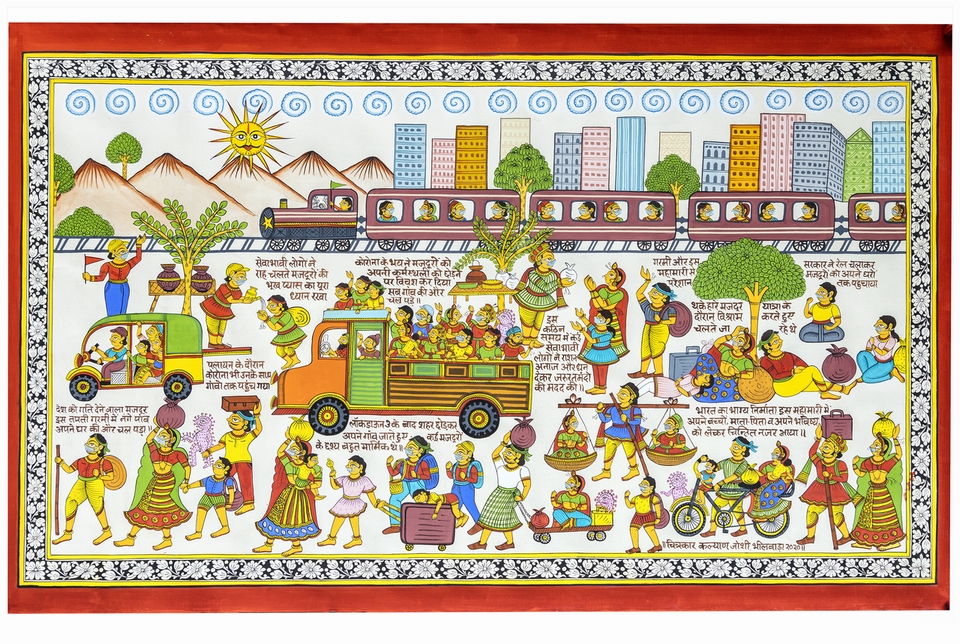

Smaller initiatives and collaborations have also broken new ground in providing opportunities and audiences for regional artists. The art centre Art at Anangpur was established in 2019 to bridge the urban–non-urban divide. It has fostered opportunities for artists from a range of remote locations and communities across India through the work of curator Minhazz Majumdar, a long-time advocate and organiser for indigenous and rural artists, who has facilitated collection-building in museums around the world.8 When Art at Anangpur was forced to close its doors due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Majumdar commissioned artists from across India to respond to the crisis, initiating an incredible artistic outpouring from some of the most vulnerable artists in the country.

These recent initiatives and events have positioned regional practices on an unprecedented scale and reach, however it is important to note the role artist collaboration has played. Throughout the twentieth century, ‘urban’ artists in India have been primarily responsible for the foregrounding of indigenous and regional practices. This began with students interacting with members of Santhal communities at Santiniketan, and, from the 1950s, at the Weavers Service Centre, where artists such as KG Subramanyan and Bhaskar Kulkarni documented little-known practices. These developments came before the influential work of Swaminathan and, subsequently, a generation of artists based in Baroda, a number of whom would continue to draw on their exposure to regional traditions in their careers as contemporary artists. Collaborations based on this tenet of reciprocity are now increasing as artists from inside and outside the contemporary canon see opportunities to develop new forms of art.

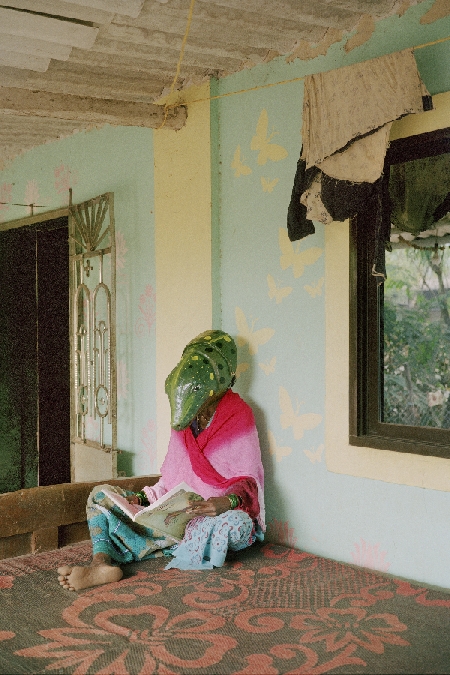

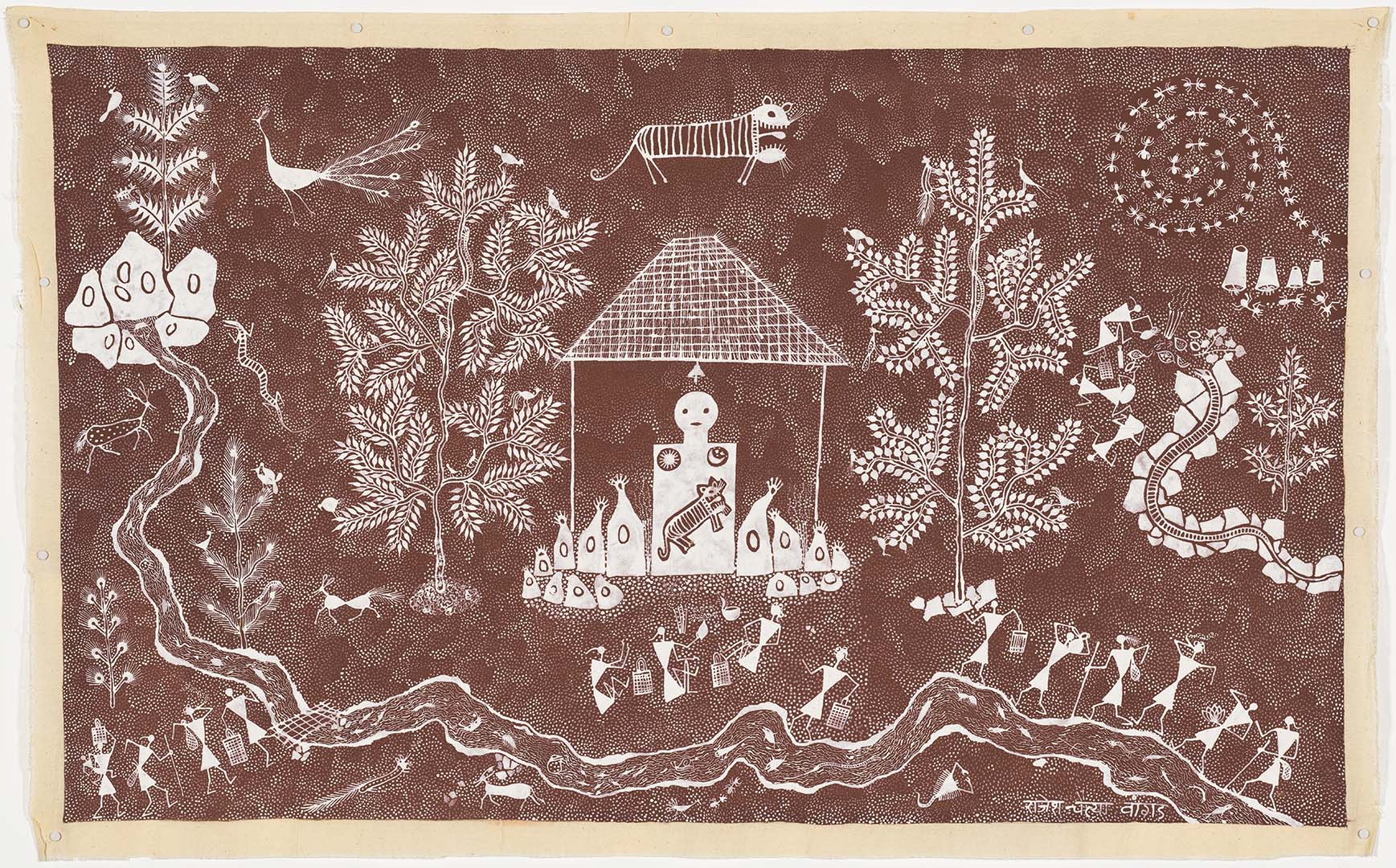

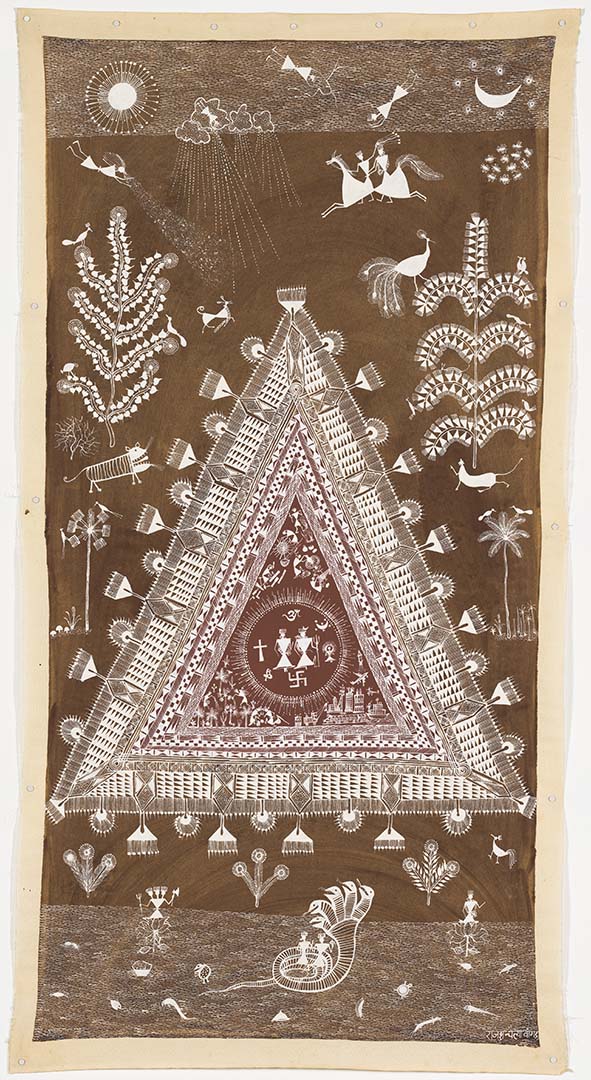

Some of the most iconic images of creative exchange are those involving renowned photographer Gauri Gill and the established Warli artist Rajesh Vangad, which also signal the many years of the pair advocating and developing platforms for Adivasi artists. Their long-running partnership began when Gill visited the Thane district and met Vangad in 2013, soon resulting in the renowned and still ongoing ‘Fields of Sight’ series, first exhibited at Experimenter gallery in Kolkata in 2014 before featuring in exhibitions around the world. Gill’s images of the community became the ground for Vangad’s paintings in celebrated works that emanate sensitivity and equity in their collaboration where the artworks are attributed equally and all profits are shared. Gill’s visit to Vangad’s homeland also led her to the neighbouring indigenous Konkan peoples in the Jawhar district of Maharashtra where she encountered the Bahoda festival, famous for its papier-mâché mask-making. Here she continues and extends the collaborative process in making photographs featuring newly commissioned masks, working with leading papier-mâché artists Subhas and Bhagvan Dharma Kadu and more than 30 members of the local community, for the ‘Acts of Appearance’ series, since 2015. Both series have forged rare pathways for Adivasi artists to be prominently featured in major international platforms, including the exhibition of the two series in 2017 at Documenta 14 in Kassel, Germany; and the series ‘Acts of Appearance’ being presented at MoMA PS1, New York, in 2018. These pioneering efforts have also led to works by Adivasi artists entering the collections of New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, London’s Tate Museum, and others.

Confronting the global canon

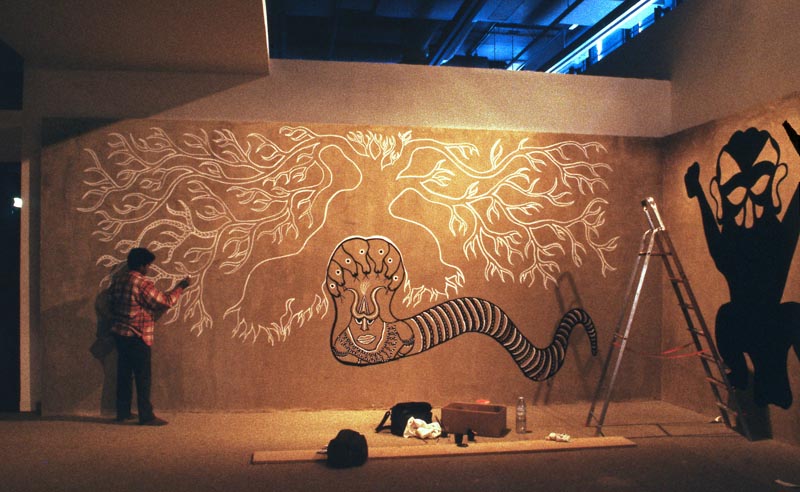

Developing platforms in India have been underscored by a concurrent internationalisation of India’s contemporary and folk art practices and, while this has fostered opportunities, it has also highlighted issues of contextualisation. Following MoMA’s 1984 exhibition ‘“Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern’, curated by William Rubin, this issue of contextualisation was famously highlighted in the contentious ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ exhibition curated by Jean-Hubert Martin in 1989 at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, for which a young Jangarh Singh Shyam created a mural of a towering Gond deity and sprawling multi-headed cobra on a large wall of the gallery.

Both Swaminathan and Jain served as consultants for the exhibition, which would propel Shyam to international fame and mark an unprecedented moment for Indian Adivasi art.9 Indigenous Warli artist Jivya Soma Mashe had also been invited to exhibit at the Pompidou, and his work appears on the catalogue cover. For reasons unknown, he never made the trip; however, Mashe was later brought together with English land artist Richard Long, and this led to a series of exhibitions alongside Long in Europe and an accompanying international reputation.10

The sudden international exposure of indigenous Indian art was complicated by Jangarh Singh Shyam’s suicide in 2001 while on residency at Japan’s Mithila Museum. His letters of the time reveal his anguish at being stripped of his freedom to return home and being forced to produce paintings.11 The tragedy — and the loss of an artist who should have been recognised as one of the great painters of his time — was a subject that cultural theorist Nancy Adajania confronted as co-curator of the 9th Gwangju Biennale, by including the artist ‘as a contemporary artistic position’ in one of the most significant biennale platforms in Asia.12 Featured in the Biennale were the artist’s final letters, highlighting Adajania’s intended gesture that ‘the folk and tribal artist is treated as a poor relation to the contemporary artist’.13

The internationalisation of practices in the 1980s and 1990s — which was only just beginning to influence India — had a mixed effect on artists from remote communities. The reluctant yet pioneering Rajwar sculptor Sonabai is said, after she first exhibited in the United States in 1986, to have completely erased the confusing experience from her memory.14 For other artists, it would have transformative effects, as Santosh Kumar Das recounts for Ganga Devi and Sita Devi, the vanguard painters of the Madhubani region:

[C]oming into contact with the wider world, they responded to new experiences and this in turn inspired paintings of [a] different nature, ones that described the artists’ journeys and experiences beyond their cultural boundaries.15

A series of encounters between Australian artists and organisations and India’s Adivasi and ‘folk’ artists have shown the tremendous value of building relationships and exploring connections preceding colonial contact. Jain has reflected that Australia led the field in acquiring works from India as fine art for museum collections, and he, as well as Swaminathan and others, has identified that Indian artists were aware of the shifts occurring in Australia.16

The year prior to Swaminathan’s 1987 landmark exhibition ‘Perceiving Fingers’, Australian Victoria Lynn visited India as a curator for the Australian artists participating in the 6th Indian Triennial; after which she spent considerable time with Swaminathan at Bharat Bhavan.17 Drawn to Adivasi art through her awareness of what was then known as ‘urban’ Indigenous Australian art, Lynn observed that the Indian art world at the time was seeking to characterise itself as part of an international contemporary art, in which Swaminathan’s work was considered idiosyncratic.18 With the help of Swaminathan, and the support of the recently established Australia-India Council, ‘India Songs: Multiple Streams in Contemporary Indian Art’ was presented in 1993 at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney. The premise of the exhibition was to showcase the work of ‘urban’ artists alongside those from a tribal or folk context, with seven artists from each sphere. In this way, it reflected the direct influence of Swaminathan’s vision at Bharat Bhavan and included works by both Swaminathan and Jangarh Singh Shyam, along with a selection of paintings and sculptures created in the 1980s to signal the transformations that had already occurred.19

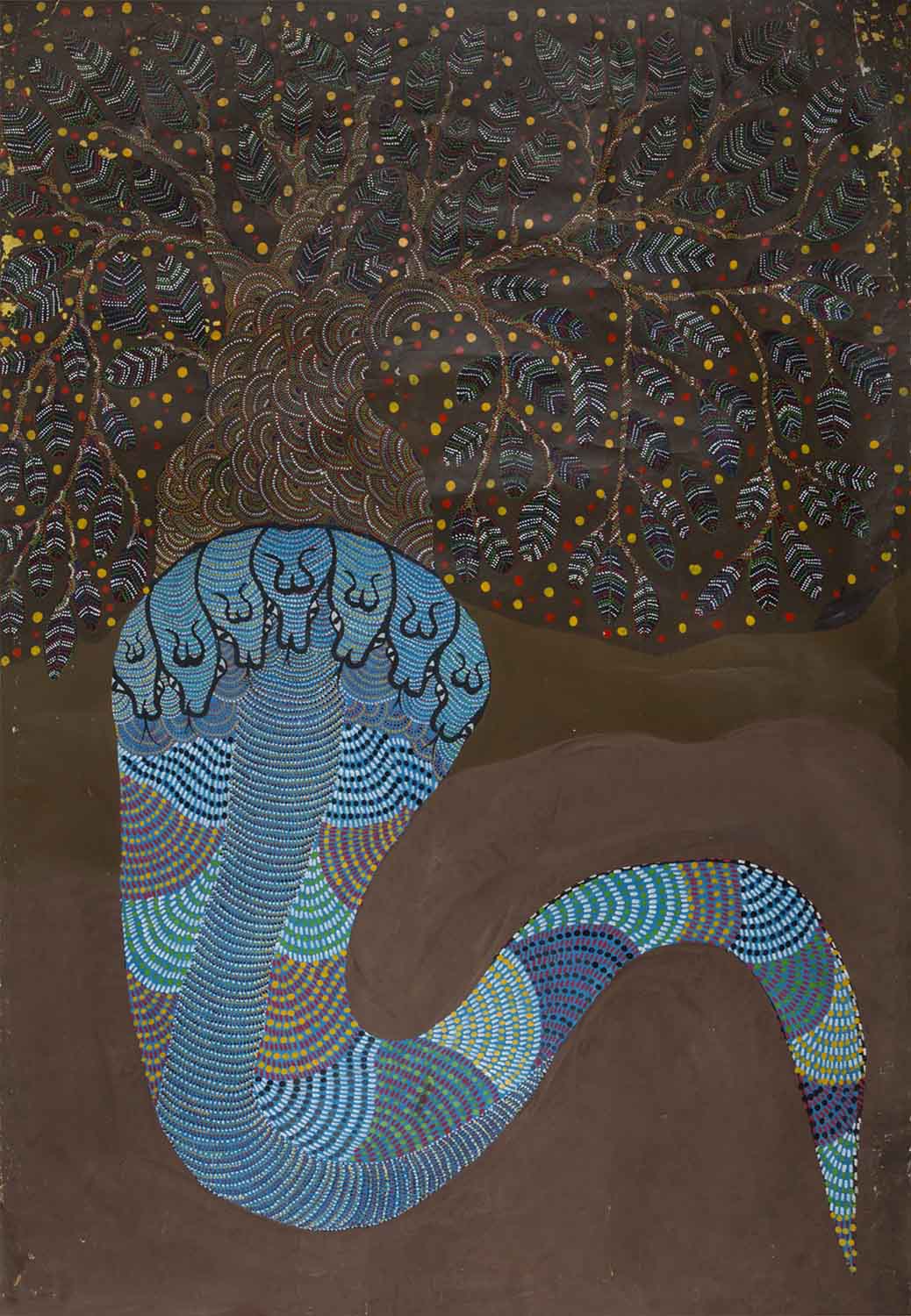

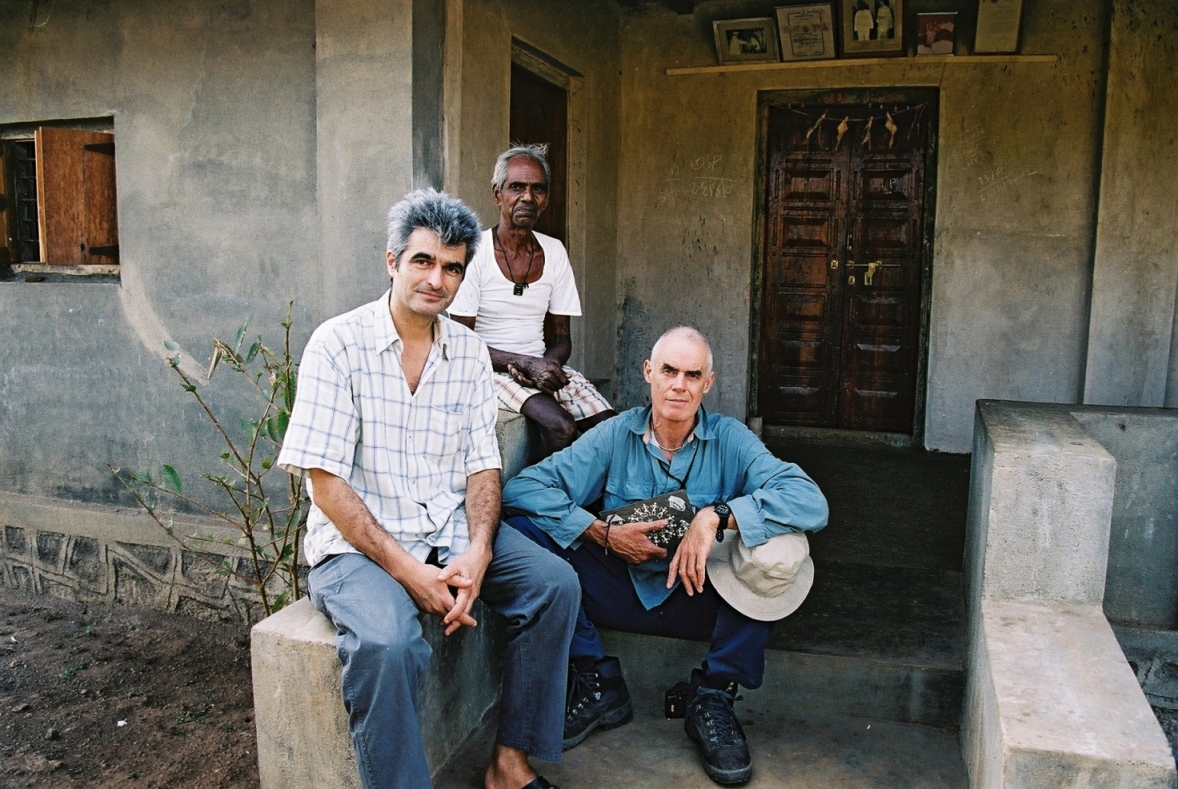

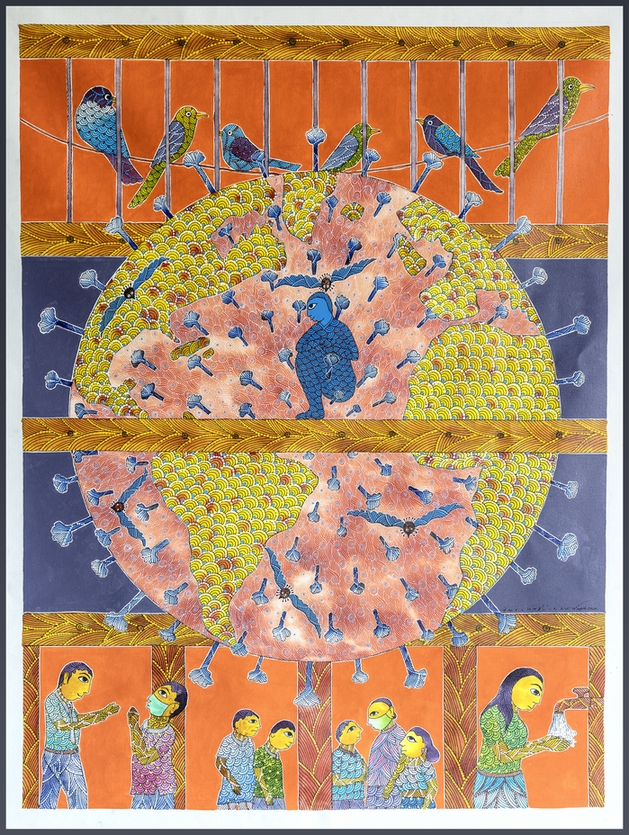

One of the few, and perhaps most significant, artistic exchanges between Indian and Australian artists occurred in 1998, when an exhibition of Indigenous Australian bark paintings, prints and carvings curated by Djon Mundine toured to the National Crafts Museum in Delhi.20 A residency by acclaimed Australian artists Djambawa Marawili and Liyawaday (Kathy) Wirrpanda, from Yirrkala in the Northern Territory, accompanied the exhibition. During the residency, facilitated by Jain at the National Crafts Museum, Marawili and Wirrpanda met Jangarh Singh Shyam and Bhil artist Lado Bai. The four artists then sat either side of two large canvases to paint together. Though the artists shared no common language, their imagery formed a conversation through representations of mythologies and cartographies. In an untitled painting, one side depicts expansive waterways with crocodiles and people fishing in canoes, while the other side features Bhil figures riding horses along a river. Landscapes and waterways meet in the centre with a crab grappling with a snake, rendered in the unmistakable patterning of Jangarh Singh Shyam. The exchange — one of the rare interactions between the indigenous artists of India and Australia — is said to have had such a profound influence on Shyam that it completely transformed Gond painting.21

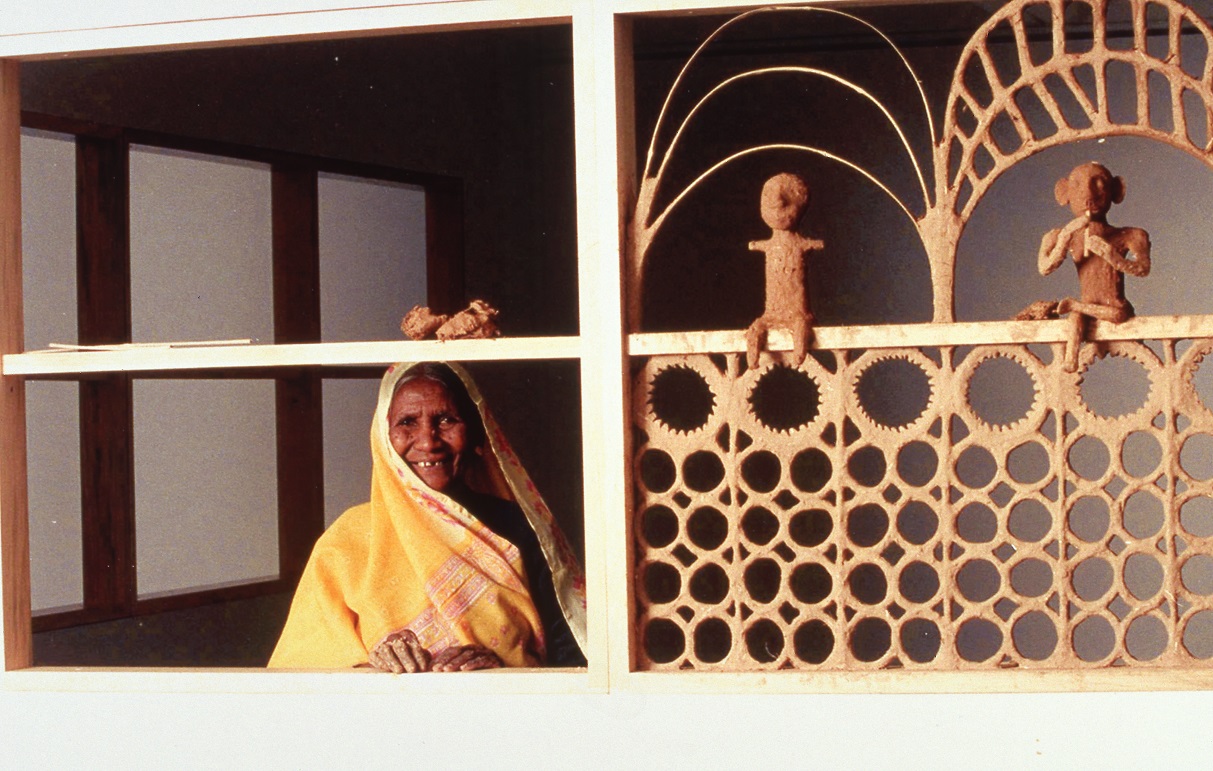

During the same period, Jain was also an advisor for the third Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT3), held in 1999 at the Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane. He facilitated Sonabai’s inclusion in the exhibition among celebrated figures of contemporary Asian art. Works by well-known Indian artists — such as Nilima Sheikh and Mrinalini Mukherjee, both of whom were heavily influenced by KG Subramanyan, Santiniketan and ‘folk’ practices — had featured in the second APT in 1996 (Victoria Lynn was an advisor for India for the exhibition). Sonabai’s inclusion, however, brought to light the contentious issue of what constitutes contemporary art on an international platform.22 The representation divided critics.23

The 2005–06 exhibition ‘Edge of Desire: Recent Art in India’ firmly embedded the work of ‘folk’ artists within its thematic sections, providing insights into different subjects of contemporary Indian culture alongside their more commercially successful counterparts. The touring exhibition was curated by Australian academic Dr Chaitanya Sambrani as a collaborative project between the Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, and the Asia Society, New York, and it also travelled to venues in the United States, Mexico and India in 2005–06. From the outset, ‘Edge of Desire’ was conceived as a point of difference from Indian art-focused exhibitions in Europe and highlighted the influence of folk art on a number of the featured artists.24 For Sambrani, the exhibition sought:

to question cultural structures that segregate and hierarchize visual practices … making a case for a polycentric aesthetic of difference rather than the rhetoric of identity and development.25

To date, the exhibition’s global reach is the largest platform on which works by artists from ‘folk’ and indigenous contexts were celebrated as valid forms of contemporary art. Thematically, these contexts were positioned to observe congruence rather than difference and, as such, successfully eschewed the ghettoisation of practices within the exhibition framework, influencing later exhibitions in India.26

Some 15 years after Sonabai’s inclusion in APT3, the Queensland Art Gallery presented Kalpa Vriksha: Contemporary Indigenous and Vernacular Art of India, a project within ‘The 8th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT8) in 2015. Kalpa Vriksha focused on a younger generation of India’s indigenous and folk artists in dialogue with indigenous and non-indigenous practices from Asia, the Pacific and Australia.27

During the event, exhibiting artist Venkat Raman Singh Shyam recalled the importance of the exchange between artists Djambawa Marawili, Liyawaday (Kathy) Wirrpanda and his uncle and teacher, Jangarh Singh Shyam, some 20 years earlier, as well as noting the deep connections felt between these indigenous cultures he could perceive through Marawili’s name:

I cannot but tell you how much the word ‘Djambawa’ means to the indigenous people of the Indian subcontinent. To some communities, labelled as untouchable, Jambawa is [the name of] their Big God, the god of gods, the Allfather. The land of the subcontinent in this oral/folk history is called Jambu-dwipa, the island of Jambava.28

Shyam has often acknowledged such connections across Gondwanaland, observed through linguistics, gotras (lineage) and the distinctive sharing of lines and dots in paintings.29

Barriers of exclusion

While groundbreaking opportunities have arisen for artists and organisations seeking to define a space within global contemporary art for India’s indigenous and regional artists, the failure to address some of the biases and imbalances confronted decades earlier pervades the present era. Venkat Shyam acknowledges that while the art market has been accepting of Adivasi art in recent times, it remains relegated to its own category and its trajectory moves in parallel, rather than inclusively, with contemporary art.30 Shyam has commented:

[A]rtists have today exhibited widely in India and abroad. We seem to have arrived, but even today most of the art world — gallerists, curators, other artists and critics — view us as ‘traditional’ artists. We still find it difficult to be recognised and accepted as contemporary artists by the arts establishment in India.31

Systemic boundaries preside over contemporary practices that affect their official categorisation in India, in turn instilling institutional hegemonies and defining commercial positions in a market that resides outside that of contemporary art. These boundaries continue to reinforce ideas of where an artist’s work is expected to be exhibited and what that work is expected to look like as anonymous and unchanging. Such categorisation bundles together the inherited cultural practices of Adivasi and regional communities with objects such as textiles and miniature painting, taking the former away from the lens of a contemporary art audience, while failing to provide access to the markets, patronage and academic study endowed to the latter. The situation is, in part, a hangover of the mass manufacture and trade of the East India Company and the colonial period that turned cultural practices into commodities, but which continue to define the market today, as Jain has observed over decades:

By lumping the professional crafts, women’s ritual paintings and objects made for personal or ceremonial use under the ad hoc label ‘handicrafts’ and then dealing with it as a commercial category has harmed the artistic and cultural content of folk and tribal arts in multiple ways … We huddle them into assembly lines of ‘handicraft’ factories, denying them scope either to retain their inherited artistic vision or for any creative experiment inspired by exposure to their contemporary situation.32

Curators and writers such as Adajania are also still compelled to question how the market continues to view artists from outside its accepted field:

we think contemporary art is the monopoly of metropolitan academy-trained artists. Do folk and tribal artists not experiment with their visual material, demonstrate technical ingenuity, respond dynamically to new experiences? And do contemporary artists not repeat their signature styles at the market’s bidding?33

A lack of critical discourse in the field is another issue, and conversations on the subject commonly allude to the fact that even appropriate terms of reference are yet to be endorsed. Curators and commentators on the subject, such as Annapurna Garimella and Minhazz Majumdar, regularly confront terms used interchangeably, such as ‘tribal’, ‘folk’, ‘Adivasi’, ‘subaltern’ and ‘vernacular’, which often prove erroneous, particularly as their etymologies are littered with negative connotations, alongside India’s caste classifications of ‘scheduled tribes’ and ‘backward class’.34

Government policy has also proved detrimental to the visibility of regional and Adivasi communities. The support of the Madhya Pradesh state government made Swaminathan’s work and Bharat Bhavan possible in the 1980s, providing specific conditions for artists to work outside the caste system in those regional communities. However, when it came to govern the state in early 1990, the Bharatiya Janata Party attacked these policies and amended the Bharat Bhavan Act to strip it of its autonomy, leading to Swaminathan’s resignation.35 Over the past few years, India’s fervent and growing nationalism has seen numerous cases of Hindu fundamentalism, caste violence, and tense border and citizenship disputes, including in India’s north-east region, where large numbers of indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities live in border areas.

Other hurdles remain in India’s global commercial art market, which fosters some of Asia’s highest-paid artists. The post-boom market — built on notions privileging individual, studio-based practices, predominantly in India’s mega cities — is difficult for any artist on the fringes to enter.36 This leaves regional artists with less economy to realise ambitious works and little space in the market for art practices that have ritualistic or cultural associations, including those that might require spaces that can accommodate certain ceremonial or cultural protocols.

While the art contexts of India have evolved in markedly different ways to the country’s neighbours, indigenous representatives have increasingly taken agency in shaping artistic and discursive platforms in other parts of South Asia. Indigenous artists are at the centre of exhibitions and discussion in Bangladesh, where artists from the Chittagong Hills feature in major exhibitions in Dhaka, and groups like the Gidree Bawlee Foundation of Arts and the Santaran Art Organization work with indigenous communities and artists on highly visible projects.37 Such projects have featured prominently at the Dhaka Art Summit, along with indigenous artists from neighbouring countries. The 2018 Summit featured the ‘Sovereign Words’ program, which brought indigenous artists, writers and thinkers together from across the world to explore issues of indigenous representation.

Contemporary indigenous practices also feature prominently in the rapidly emerging arts ecology of Nepal, where younger generations of artists are addressing their own indigeneity and working with communities. Set to become the largest contemporary art event ever in Nepal, the ambitious KTM 2077 (Kathmandu Triennale) has assigned a significant portion of its curatorial development to indigenous artists from Artree Nepal, who will take up roles as associate curators. In addition, KTM 2077 has prioritised the work of indigenous and folk artists, as well as relying on indigenous ideas in its very definition.

Evolving contemporaneity

As artists find new ways to tell their stories and represent their culture, the contemporary paradigms of Adivasi and so-called ‘folk’ practices have been subject to rapid adaptation and transformation. These developments have resulted in some critical and poignant images exploring contemporary issues in India, with shifts occurring from the iconic to the narrative — shifts that have, in turn, led to more artists depicting their social and political predicaments.38 The way practices and hereditary conventions have changed show artists’ responsiveness to contemporary contexts, revealing valuable insights into events while also reshaping artforms to be more inclusive and socially constructive.

Patachitra artists from the Chitrakar community are often acknowledged for their cinematic mode of storytelling: the scrolls are unravelled scene by scene, accompanied by song narrating a linear story.

Installation view of patachitras inside Kalpa Vriksha, within ‘The 8th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2015–16 / Photograph: Natasha Harth / (l–r) Jaba Chitrakar / Tsunami 2015 / Natural colour on mill-made paper with fabric backing / 278 x 56.2cm / Purchased 2015 with funds from Rick and Carolle Wilkinson through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation; Madhu Chitrakar / Tsunami 2008 / Natural colour on mill-made paper with fabric backing / 276.6 x 56cm / Purchased 2016 with funds from Professor Susan Street AO through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation; and Sonia Chitrakar / Tsunami 2012 / Natural colour on mill-made paper with fabric backing / 280 x 56cm / Purchased 2016 with funds from the Estate of Jessica Ellis through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © The artists

Installation view of patachitras inside Kalpa Vriksha, within ‘The 8th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2015–16 / Photograph: Natasha Harth / (l–r) Jaba Chitrakar / Tsunami 2015 / Natural colour on mill-made paper with fabric backing / 278 x 56.2cm / Purchased 2015 with funds from Rick and Carolle Wilkinson through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation; Madhu Chitrakar / Tsunami 2008 / Natural colour on mill-made paper with fabric backing / 276.6 x 56cm / Purchased 2016 with funds from Professor Susan Street AO through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation; and Sonia Chitrakar / Tsunami 2012 / Natural colour on mill-made paper with fabric backing / 280 x 56cm / Purchased 2016 with funds from the Estate of Jessica Ellis through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © The artistsWhile earlier examples focused on religious subjects, more recent works by younger generations of painters have depicted subjects such as the terrorist attacks of 11 September, versions of Hollywood films, and natural disasters. These artists have also been employed by charities to disseminate health campaigns in remote village communities. Others promote their own messages, highlighting pressing social issues, such as the treatment of women in vulnerable communities, as well as experiences relating to the COVID-19 pandemic.39

Venkat Raman Singh Shyam / Signal 2009 / Ink and synthetic polymer paint on paper / 75.2 x 54.8cm / Purchased 2016 with funds from the Estate of Jessica Ellis through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Venkat Raman Singh Shyam

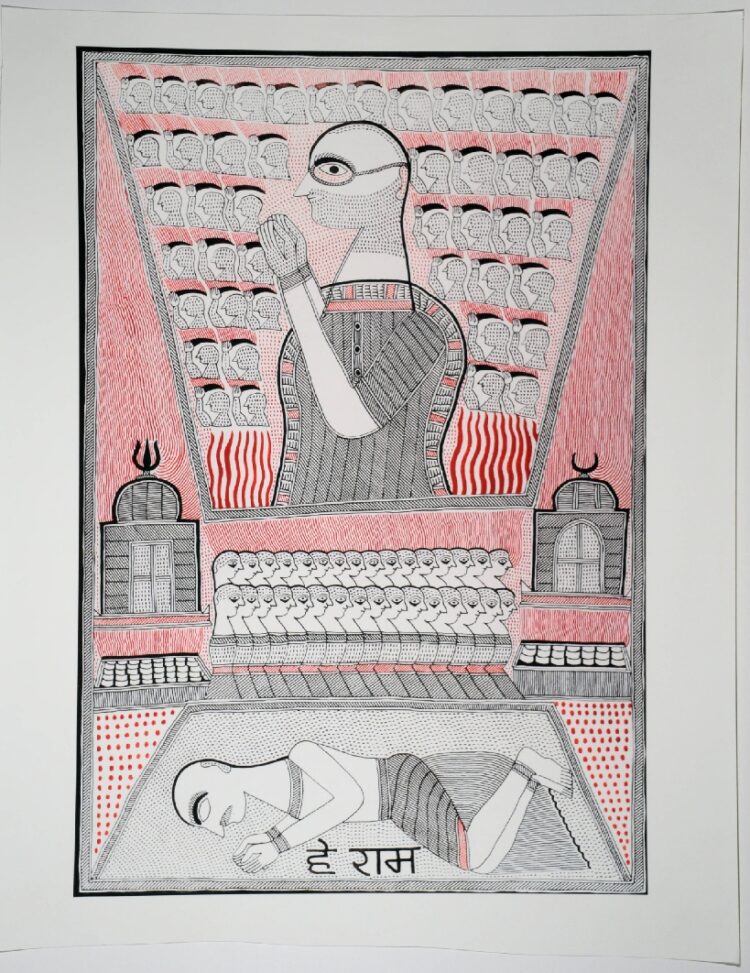

Venkat Raman Singh Shyam / Signal 2009 / Ink and synthetic polymer paint on paper / 75.2 x 54.8cm / Purchased 2016 with funds from the Estate of Jessica Ellis through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane / © Venkat Raman Singh ShyamArtists reflect individualised experiences expressed through unique visual languages: when Venkat Raman Singh Shyam found himself in Mumbai during the 2008 terrorist attacks, he was inspired to transform his experience into a renowned series — which features renderings of smoking hotels, police vehicles, and semi-abstracted forms interpreting the terrorists’ arrival in the Mumbai fishing village — using the complex line work of Gond art, a technique he had practised from a young age. Similarly, Santosh Kumar Das’s 2003 series about the 2002 communal riots in Gujurat showed powerful insights into the devastatingly violent event while also revealing poignant political undertones, all rendered in the monochrome detail of Mithila art, most notable in the work titled Chief Minister Narendra Modhi Inciting Religious Intolerance While Gujurat Burns and Gandhi’s Death is Forgotten.40

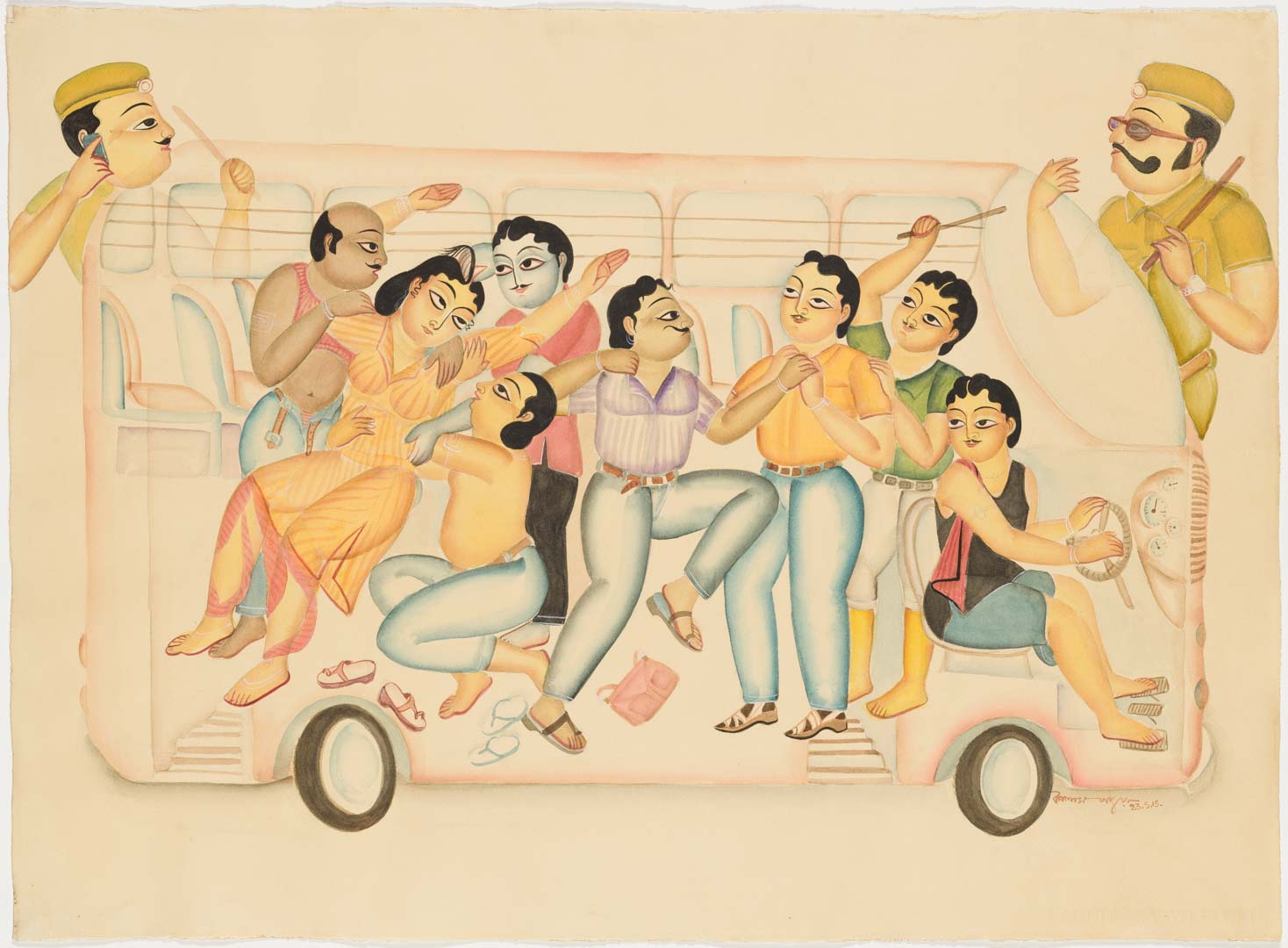

Artists from vulnerable regions and communities have often produced confronting images that unveil social inequalities. The infamous 2012 ‘Nirbhaya’ gang rape and murder case in Delhi has been a source of haunting symbolism for artists engaged in contemporary modes of Patachitra, Mithila and Kalighat painting. The vulnerability of women and the violence perpetrated against them is a subject explored by Pushpa Kumari, one of the leading contemporary exponents of Mithila painting, whose works have also addressed dowry, infanticide and the stigma faced by female children. Originally from Madhubani in Bihar, a state often described as the poorest and most ‘backward’ in India, Kumari transforms these subjects through the mythological symbolism of Mithila art.

Adivasi and folk artists have found ways to break the exclusionary barriers of gender, class, faith and language that previously defined their practices by responding to needs of social inclusivity and the maintenance of cultural traditions. As art becomes more mobile and is produced for contexts beyond the community, distinctions of class and language are being challenged. The itinerant role of the Patachitra painter, for example, relegated the occupation to an almost exclusively male one; however, some women painters, now going back two generations, are recognised as prominent figures in the art form today. The women’s practice of Warli painting, originally produced on huts for marriage ceremonies and festivals, has since been produced by men on paper and cloth, and is now practised by a number of women and men from younger generations. Mithila art, known as women’s art with a long history, is now led by both women and men. A deeper caste division has also been overcome in Mithila art; originally open only to artists from an elite section of society, it is now taught to any student of the Mithila Art Institute, as well as to artists in other parts of the country.41

Religious and cultural syncretism is a notable element of the contemporary transition for Adivasi and ‘folk’ art, alongside aspects of secularisation in what were once primarily spiritual indigenous art forms. For instance, the originally Muslim communities of Patachitra painters from West Bengal continue to produce vast narrations of Hindu stories for Hindu patrons. Such fused belief systems are also inherent in the deified figures of Gond painting, which regularly pairs Hindu and indigenous Gond gods, and in Warli painting, where other religious festivals and icons are commonly subsumed into a pantheon of indigenous symbolism, ritual Warli lands and cosmopolitan life. These examples of syncretism and adaption reveal how indigenous and ancient ethnicities have evolved through a palimpsest of peoples, languages, interactions and belief systems, and their art forms have similarly melded into myriad expressions.

Broader access to education and travel has seen artists breathing new life into their art practices, by welcoming opportunities to promote their art and culture to wider audiences; significantly, at the same time, they are exposed to the need to maintain cultural authenticity. This approach is exemplified by the young, university-educated pair Tushar and Mayur Vayeda of the Warli community in Ganjad, who have been taking the art of their community in ambitious new directions through publishing, participation in international exhibitions and creating collaborative murals and large-scale installations. They maintain close contact with senior artists and have developed an astute awareness of the effects of both commercialisation and appropriation on authenticity, recognising the need to encourage young artists to maintain cultural protocols while realising new opportunities.42

In order to compete with the singular notion of urban practices, older generation regional artists often required a mode of representation based on individuality to gain entry into the wider art market; however, collaborations are now challenging an art world predicated on individuality. Practices that serve multiple purposes, while remaining relevant to community, show forms of ethnic collectivity that have proven to be both adaptable and adept at nurturing new modes of art production.43 This is evident in the way that Chitrakar artists share subjects and song, with groups of artists commonly interpreting the same subjects and stories while learning from each other. Similarly, the once-reclusive sculptor Sonabai eventually led workshops that guided the next generation in developing the art form, with her isolated house now an artistic centre fostering new learning.

The Dialogue Interactive Artists Association (DIAA) project in Chhattisgarh has also facilitated collaborations involving artists — both local and from outside the district — who work with community on projects that support local development needs. These examples reveal opportunities for indigenous and non-indigenous artists to facilitate sharing and exchange.

The early pathways that introduced Adivasi and folk art into contemporary art discourse in the 1980s tendentiously unveiled the systemic hegemonies and exclusionary perspectives that continue to be navigated today. However, recent decades have revealed that art forms, stories and communities have survived, adapted and thrived through the work of artists, who, as Dr Jyotindra Jain described for ‘Other Masters’, fail to ‘see themselves as waiting outside the precincts of the world of “modern art” to be absorbed on the latter’s terms’.44 These artists have brought forward modes of contemporary art-making that not only demonstrate the need to participate in established platforms, but the capacity to design their own structures for sharing cultural knowledge and to develop their own artistic, discursive and community-driven frameworks. As such artists and communities define their place within broader systems of contemporary culture, they are unlocking new possibilities and parameters for the development of contemporary art.