There is a crack in the ocean. Deep beneath the flake of reef, beneath the darting parrotfish and unicornfish and slippery eel, the earth gapes, an open mouth. Deeper still, past the lips of the trench, the black throat of the earth lies empty, a hollowness where no light can reach. Yet thirty-six thousand feet above, a glinting string of islands — and in the middle, Guåhan floats in the sun.

— Lehua M Taitano, The Beginning. Before Time1

Dawn approaches Guåhan (Guam) on 22 May 2016 and downtown Hagåtña is a hive of activity. Groups of people hasten towards the marina, weaving their way through the newly constructed Festival village to the dark silvery outline of the shore. Throngs of people crowd along the length of Agana Bay, climbing over rocks to get a better look out towards the horizon. There is laughter and teasing amidst a gentle jostling for space, as those gathered wait for the sun to pierce through the pinky haze, hoping to catch a first glimpse of the boats waiting at the pass beyond the reef.

The convoy of sailing vessels has been guided here by seafarers from islands across the northern Pacific. There are ocean-going canoes from Lamotrek Island in Yap State, Poluwat (also referred to as Polowat) and Houk Islands in Chuuk State, the Northern Mariana Islands and Guåhan (Guam) itself. From Palau, the celebrated vessel Alingano Maisu has made the week-long journey with Sesario Sewralur at the helm. Sewralur is the son of renowned navigator Mau Piailug, whose decision in the early 1970s to share the navigational knowledge taught him by his elders inspired a new generation of seafarers to train in the customary arts of Pacific wayfinding. This spearheaded the revival of long-distance, non-instrument voyaging throughout the region.

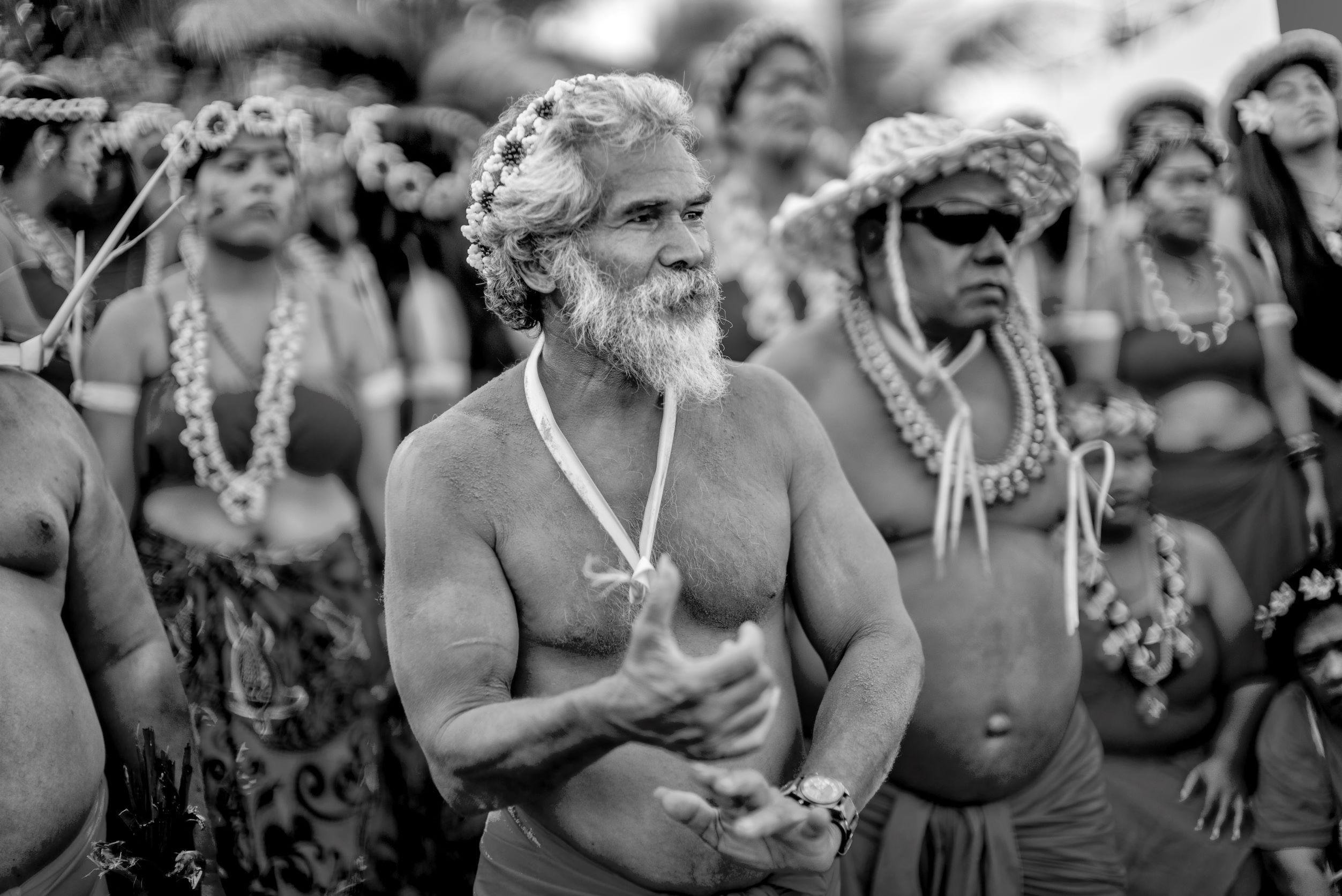

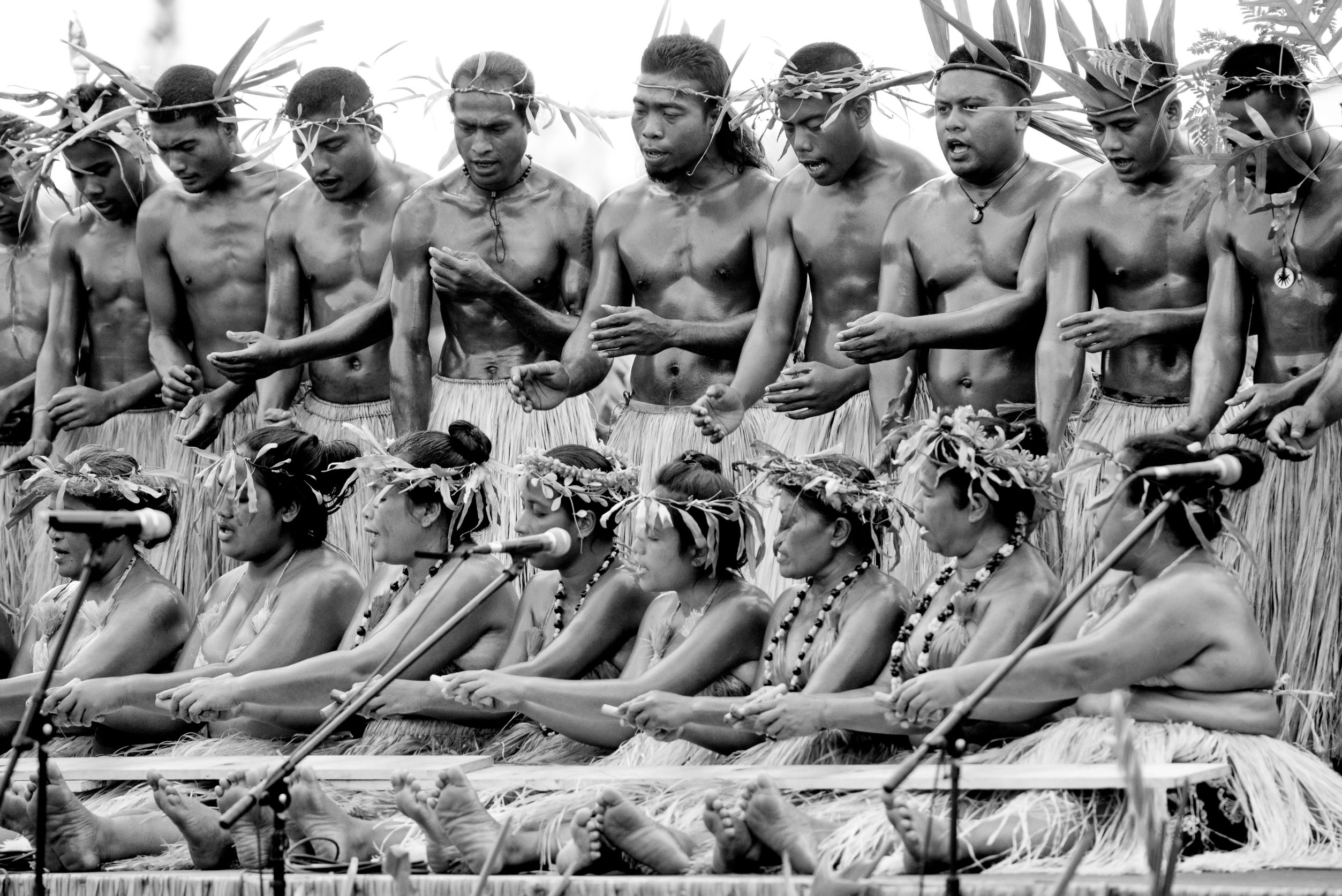

As each vessel begins its final approach to shore after weeks at sea, crews set about lowering sails, and waving and beaming smiles to the thousands gathered along the glittering coast. The CHamoru hosts, recognisable in their distinctive marigold-coloured headbands, step into the shallows to greet their Pacific guests, acknowledging their arrival with ceremonial gifts and chants of welcome. Young and old stand together to receive the visitors, who graciously accept the gifts presented to them as each vessel approaches the landing point. The ebb and flow of songs and speeches reaffirms the deep ancestral ties connecting these communities: simple yet powerful exchanges reassert the reciprocal bonds that have bound widely dispersed Pacific peoples for generations.

Every four years, delegations from some 27 Pacific Island nations and territories come together at the Festival of Pacific Arts to share in a special celebration.2 The 12th Festival of Pacific Arts, hosted by Guåhan (Guam) (22 May – 5 June 2016), was the largest cultural event ever to have taken place on the island. The dawn welcome for the voyaging boats was a momentous gathering, anchored in customary protocols that set a celebratory tone for the rich cultural exchanges for the two-week duration.

Each iteration of the Festival sees several thousand practitioners come together in a showcase that celebrates Pacific arts and culture in disciplines as varied as the visual arts, oratory, dance and performance. Established almost 50 years ago as a platform for intercultural exchange, the Festival is often described as the ‘Olympics of Pacific arts’. It is a prestigious event and, though not a competition, delegations bring their best game, letting island rivalries play out in a healthy, competitive, yet collaborative, spirit. The theme selected by the Guåhan (Guam) planning committee for 2016 was ‘Håfa Iyo-ta, Håfa Guinahå-ta, Håfa Ta Påtte, Dinanña’ Sunidu Siha Giya Pasifiku’ / ‘What we own, what we have, what we share: United voices of the Pacific’ — a perfect encapsulation of the aims and ambitions of this unique regional gathering.

From the beginning, the focus of the Festival has been to celebrate the cultural heritage of Pacific Islanders by promoting customary arts, encouraging the use of indigenous languages and stimulating new forms of artistic expression. Alongside visual arts, such as painting, sculpture and the fibre arts (weaving, binding and textiles), the Festival celebrates Pacific architecture, film, theatre, fashion and design, and is constantly evolving its format to accommodate innovation and the diversity of Pacific cultural expression.3 Space is given to indigenous practitioners who showcase the artistry and customary skills involved in tattooing the skin or manipulating the body with traditional medicine and healing techniques. More recently, the culinary arts have joined the Festival line-up with an emphasis on food sovereignty.

The depth of knowledge and interpretive skills required to master long-distance navigation remains an important arena of interest, and the 2016 Festival featured a major Canoe Summit, which brought together practitioners to discuss ways to strengthen and safeguard this intangible cultural treasure into the future.4 This highlight of the Festival culminated in a series of initiation ceremonies that recognised the achievements of master navigators, whose commitment over the past five decades has led to the flourishing of open-sea voyaging. It is this concept of mastery — the deep knowledge and expertise developed over a lifetime — that is so intrinsic to the cultivation of arts practice in the Pacific. Practitioners hone their skills in the months and years leading up to each Festival, and it is this active and engaged practice that is at the core of the event and contributes to its lasting success.

Poluwat navigators pose after the Traditional Navigator Initiation (Pwo) Ceremony at the Canoe House at Hagåtna marina, Guåhan (Guam), 2016; Front row, from left: grand master Raymond Edward and Mariano Benito; back row, from left: Selvio Ainam, Larry Raigetal, Mario Benito and Aidel Martin / Photograph: Manny Crisostomo

Poluwat navigators pose after the Traditional Navigator Initiation (Pwo) Ceremony at the Canoe House at Hagåtna marina, Guåhan (Guam), 2016; Front row, from left: grand master Raymond Edward and Mariano Benito; back row, from left: Selvio Ainam, Larry Raigetal, Mario Benito and Aidel Martin / Photograph: Manny CrisostomoIf culture is the glue that binds generations of Pacific peoples together, it is the Festival that creates the vital channel through which the archive of customary knowledge is kept alive.5 This sense of cultural wealth, vested in the region’s leaders, artists and practitioners, is encapsulated in the words of Manny Crisostomo, the Pulitzer Prize-winning CHamoru photographer:

We are grounded in tradition. The past is made present through us. On our lips are the words of our ancestors. These were their stories, dress and motion. This is how they took wood, fire, beads, shells and mud, and made them speak.6

The focus of Pacific art and its production rests not with individuals, but with the collective whose energies sustain and ground the Festival.

Festival beginnings: Fiji (1972), New Zealand (1976) and Papua New Guinea (1980)

The concept of a regional festival for the Pacific originated in 1965 when members of the Fiji Arts Council envisioned an event to stimulate the arts. Hosted by and for Pacific peoples, they hoped an indigenous-led festival would encourage artists and leaders to share their cultural knowledge and safeguard it for future generations. In 1972, the idea came to fruition when the South Pacific Commission (SPC) supported the Arts Council in hosting the first South Pacific Festival of Arts in Suva, Fiji, under the banner ‘Preserving culture’. Four years later in 1976, Māori hosted a second gathering in Rotorua, New Zealand, which took ‘Sharing culture’ as its overarching theme, and in 1980, a newly independent Papua New Guinea marked five years of freedom from colonial rule with a third Festival of Pacific Arts, held in Port Moresby with the theme ‘Pacific awareness’. Highlights of these early events included a showcase of customary dance and the construction of a Festival village as a natural gathering place at the centre of proceedings, both of which remain essential components of the current format.

The 1970s and 1980s would come to be defined by this growing movement towards Pacific unity, and the Festival has played an important role in helping engender this strong sense of community amongst Pacific nations disrupted by colonialism. The long-term exploitation of resources, including mineral extraction, that began in the nineteenth century, and the forced migration and enslavement of islanders to support these industries, had led to the division of ancestral lands into a dizzying array of formally constituted territories and states. The cultural and political map of the Pacific remains a complex one. For centuries, a bewildering range of European, American and Australasian powers have attempted to govern, exploit and claim sovereignty over Pacific peoples causing further dislocation and fracture, while during World War Two, the islands of the Pacific were subjected to intense acts of war that claimed numerous casualties. In the Cold War era that followed, the United States, France and Britain embarked on a horrific campaign of nuclear testing in the Pacific, and these island nations have borne the brunt of the global nuclear age ever since.

During the early 1970s, Fiji was a centre for grassroots activism protesting against nuclear testing, eventually becoming the home of the burgeoning pan-Pacific movement. In 1970, the anti-nuclear protest movement began in earnest with the formation in Fiji of ATOM (Against Testing on Mururoa), a group whose membership included women’s groups and church community leaders, as well as students, teachers and unionists. All were committed to educating the public about the dangers of radioactive fallout. ATOM united the broader Pacific community in a steadfast rejection of the nuclear weapons testing that was underway in its own backyard. The first Conference for a Nuclear-Free Pacific took place in Suva in April 1975 (just three years after the first Festival of Pacific Arts), and was hosted on the campus of the Pacific’s first university. An overwhelming sense of unity and support emerged from this historic meeting. Despite the long distances separating islands, 90 delegates assembled to discuss the issues directly endangering Pacific communities. The gathering laid the foundations for an activist network — the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific movement (NFIP) — and galvanised political resistance throughout the region.

According to Rotuman playwright and film director Vilsoni Hereniko:

The first South Pacific Festival of Arts marked a very important turning point in the feelings of the peoples of the South Pacific. For years, the islands had been dominated and undermined by colonial powers. Their cultures and way of life had been frowned upon, suppressed in many cases . . . With independence and self-government, it became necessary for island governments to look for some sort of national identity . . . and there was a resurgence, a cultural revival, a searching into the past.7

In carving out a space where Pacific arts and culture could be celebrated communally, the first festivals played a significant role in raising this consciousness, helping to create the conditions for a Pacific-wide solidarity that would thrive despite the distinct colonial histories that separated individual islands.

The 1970s was a formative era for Pacific literature, new art forms and emerging markets, greatly influenced, according to Pacific poets Teresia Teaiwa and Selina Tusitala Marsh, by an ‘ascendant Pacific regionalism and nascent intelligentsia class in Fiji’.8 Alongside its promotion of a new Festival of Pacific Arts, the South Pacific Commission also achieved its ambition to establish a university that would provide vocational training in the heart of the region.9 The University of the South Pacific (USP) became a strong advocate for this new brand of Pacific regionalism, and in 1976, established the Institute of Pacific Studies under the leadership of academic Ron Crocombe. This important new forum encouraged a rich intellectual discourse that transcended national borders.

Under the guise of the Institute, the region’s brightest scholars and thinkers — poets, economists, political scientists and philosophers — came together regularly for discussion and debate. New networks of scholarship thrived in this environment, inviting a generative way of thinking about the Pacific by an emerging generation who reframed outsider perspectives of the region through a local, indigenous lens. The interdisciplinary activity of campus life allowed for vital cross-pollination with the arts, creating many opportunities for both students and faculty to think through political and cultural issues facing the region, not from the sidelines, but as significant players on the global stage.

Two figures in Pacific art and literature stand out during this transformative era. In 1974, writer and poet Albert Wendt moved to Suva to take up a position at USP, becoming an important voice in the energetic intellectual environment that was taking root there. Wendt encouraged all the peoples of the Pacific to recognise and celebrate their cultural diversity. His early edited volumes of poetry brought together writing from Fiji, Samoa, the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu) and the Solomon Islands, and presented a synergistic vision of the islands, one which allowed for an excavation of common cultural precepts whose resonances reinforced the region’s underlying congruence.10 He wrote a number of plays for the inaugural South Pacific Festival of Arts in 1972.

During the 1970s, fervent debates relating to tradition (and the perceived limits of its ‘authenticity’) were playing out. Wendt guided this discussion in his seminal essay ‘Towards a new Oceania’, published in 1976 for the first issue of the literary journal Mana Review.11 In it, he urged Pacific peoples to embrace change and opportunity: ‘No culture is ever static and can be preserved . . . like a stuffed gorilla in a museum’, insisting ‘The only valid culture worth having is the one being lived out now’.12 For Wendt, artistic activity was an urgent corrective — an absolute and necessary recourse towards ‘breaking from the colonial chill and starting to find our own being’, where self-expression was ‘a prerequisite for self-respect’.13 Wendt believed above all in the power of community and its value in art-making and production, understanding that it was precisely this aspect of engagement and participation that would revitalise Pacific communities and bring necessary healing.

Another voice in the confident re-imagining of the Pacific was poet and anthropologist Epeli Hau’ofa, who joined the USP community as a research fellow in its early days. Nurtured by the interdisciplinary interactions, Hau’ofa began to outline an equally ambitious reconceptualisation of Oceania in his poetry and novels, culminating in his influential 1993 essay ‘Our sea of islands’.14 Viewing the vast expanse of ocean that defined the region as pathway more than boundary, he underscored the ancient genealogical networks that linked Pacific Islanders, emphasising their connections, rather than their separation. This recalibration of perspective from an indigenous viewpoint staked a bold claim for Pacific creativity and autonomy. Hau’ofa would go on to establish the Oceania Centre for Arts and Culture (OCAC) at USP in 1997, enhancing the University’s status as a dynamic and stimulating forum for the region’s leading performers and creative thinkers.

At this time, the vision of a Pacific future was strong. Both Wendt and Hau’ofa reclaimed intellectual and philosophical territory for Oceania, destroying the limitations of European imaginings to which it had been tethered for the past five centuries. Their vision was expansive, their storytelling epic. An entirely new generation of Pacific artists and performers, writers and musicians would take their lead in the years that followed, enthusiastically embracing every opportunity to celebrate creative expression and enforce Pacific autonomy.

In the visual and performing arts, USP also played a critical role in spearheading a series of regional art workshops, including several on art and dance that were organised at USP satellite centres across the Pacific. One of these early events, held in Honiara in 1975, featured Kuai Maueha, a skilled artist and carver from Bellona Island, who had honed his skills in Honiara and held his first solo exhibition at the Solomon Islands National Museum in 1974. Maueha went on to become the inaugural artist-in-residence, in 1976, for the USP in Fiji, where, supervised by Albert Wendt, he produced art, participated in talks and seminars, and organised an exhibition of his work.15

In other parts of the Pacific, artists, poets and playwrights were also mobilising. In 1973, the now-famed inaugural hui (gathering) of the Māori Artists and Writers Society took place at Te Kaha marae on the east coast of New Zealand. Māori creatives seized on the hui as an opportunity to consolidate their own specifically Māori aspirations for the arts, drawing boundaries that would clearly distinguish their practices from those of Pākehā (New Zealanders of European descent). The meeting, convened on customary Māori land, uplifted Māori and indigenous voices to counterpoint the mainstream art scene that dominated in New Zealand. Three years later, New Zealand would host the second iteration of the Festival of Pacific Arts in Rotorua, a cultural hub for Māori performing arts and culture since the late nineteenth century.

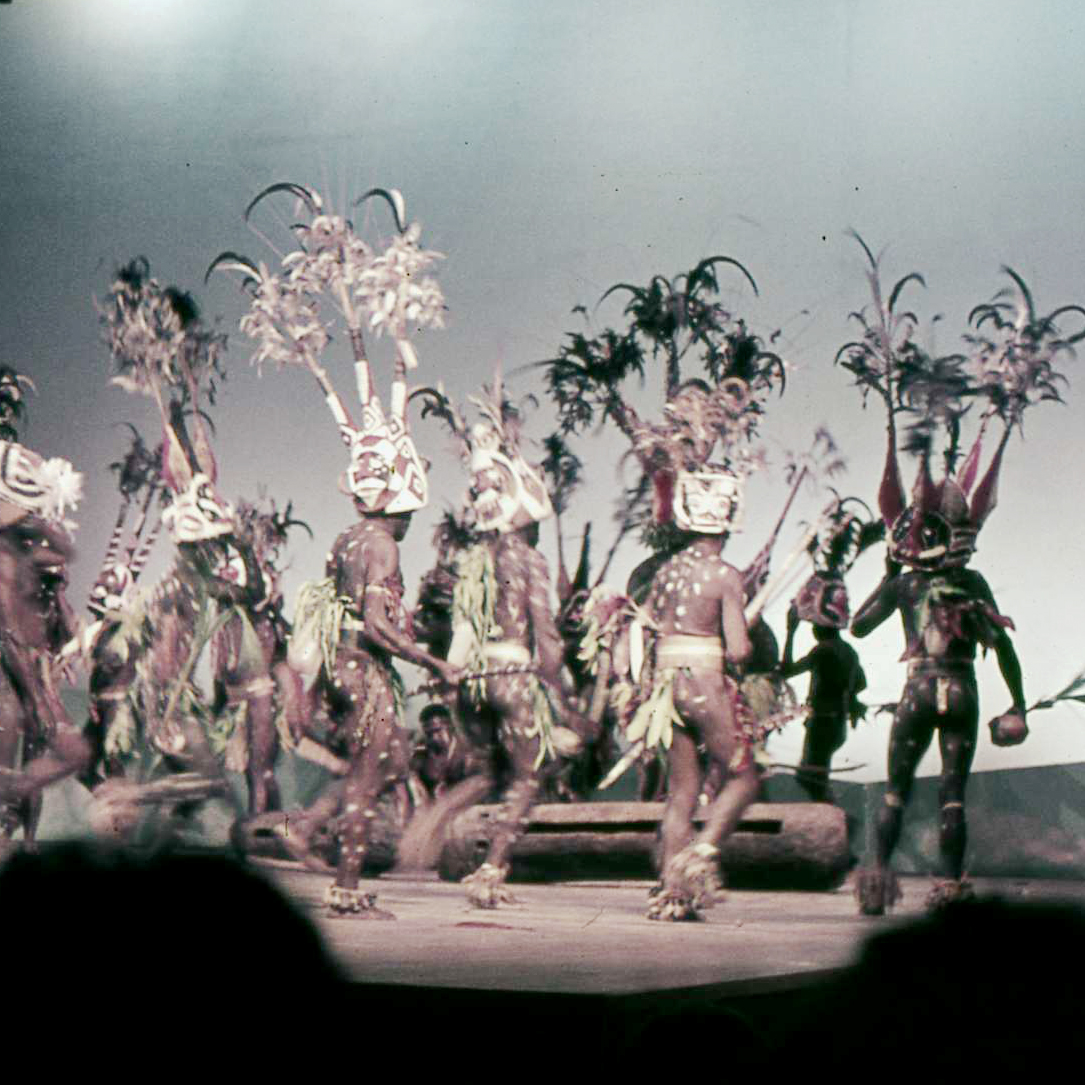

In 1975, a newly independent Papua New Guinea was also undergoing an artistic flourishing in architecture, theatre and the visual arts, as it looked to strengthen a new national identity for its peoples.16 As well as a new Parliament House, planning and construction for a purpose-built National Museum and Art Gallery had begun in 1975, and both buildings were breathtaking blends of customary and modern architectural styles.17 New Guinea artists played important roles in guiding the transformation of local vernacular architecture into these new expressions of the country’s aspirations, further steering the traditional knowledge base of kastom (traditional culture) towards exciting new genres of theatre, music and performance. Some of these new productions toured to Australia and London, where they raised the profile of Pacific arts and culture with international audiences.18

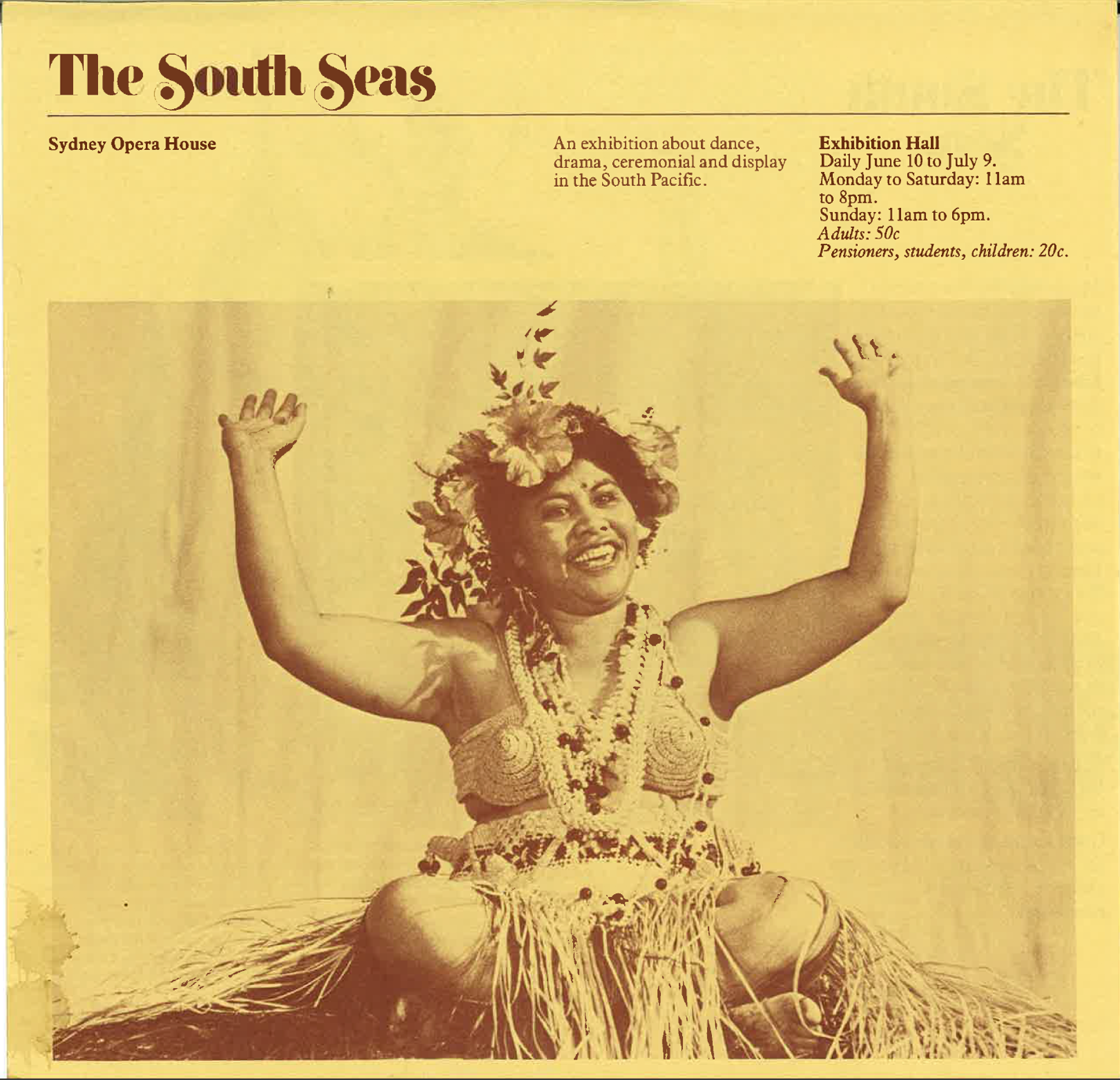

In Australia, institutions like the Sydney Opera House also played important early roles in promoting international interest in Pacific cultures, specifically through the medium of dance. ‘The South Seas’ was a month-long exhibition ‘about dance, drama, ceremonial and display in the South Pacific’, held at the Opera House in 1976, which came about largely through the efforts of Victor Carrell and Beth Dean, strong advocates for Pacific dance and the performing arts. From filming treks to the New Guinea Highlands in the mid 1950s to establishing early performing arts groups, like the Cook Islands National Arts Theatre in 1970, Carrell and Dean’s determination to raise the profile of Pacific customary dance helped establish it on the world stage.19 They were also the directors of the first South Pacific Festival of Arts, in Suva, Fiji, in 1972, and they were, as researcher and curator Kirk Huffman has noted: ‘a force to be reckoned with . . . absolutely essential in the drive to get the Festival initiated, inaugurated and accepted as a regular and important cultural initiative’.20

Since the first festivals in Fiji (1972), New Zealand (1976) and Papua New Guinea (1980), the gathering has gone from strength to strength, broadening its reach as a dynamic space for intercultural connection and exchange across Oceania, and becoming a forum where islanders can come together to celebrate the vitality and vibrancy of Pacific arts on their own terms.21 This sampling of concurrent regional initiatives underscores the extent of dynamic interaction underway from the late 1960s into the 1970s, when the earliest iterations of the Festival were taking place. Artists and advocates were establishing a wealth of creative networks in different centres across the Pacific, and setting the scene for a newly connected theatre of artistic endeavour, one that firmly centred local voices and aspirations against a background of increased self-advocacy.

Celebrating indigenous values: Guåhan (Guam) 2016

In the Pacific, art is unquestionably an intrinsic part of life — it mediates life and brings people together. Activated by performance and the collective, encounters with art are fluid and dynamic. Alongside the question of what art is, there rests a far richer account of precisely what art does. Far from being a separate sphere, the creation of art and the community who participates in its expression provide the foundation for life. From the beginning, the fundamental practices supporting art and cultural life in the Pacific — hospitality, reciprocity and exchange — have been part of the DNA of the Festival of Pacific Arts. For islanders, the Festival has become a showcase of innovation highlighting the living kaleidoscope of Pacific cultures. As delegations strive to display their best, they constantly raise the bar for their work, due to exposure to other traditions. For the 6th Festival of Pacific Arts in Rarotonga, in 1992, New Caledonia and New Zealand sent modern dance groups in support of the Festival’s remit to look to the future, as well as the past. In his welcome address, Prime Minister Sir Geoffrey Henry of the Cook Islands encouraged this development, asserting:

. . . culture is not just the past. It is the present and future. It is what we once were, but it is, also, what we hope to be . . . For nearly two weeks, we will be one even as we demonstrate our precious differences.22

This regular infusion of energy has had a rejuvenating effect on the Festival, encouraging transformation and an evolution of art styles. Elders mix with younger generations bridging gaps between customary expression (the more ‘traditional’ culture styles) and the aspirations of emerging artists, creating vibrant new genres that mix (and remix) modes of cultural expression. This precedent continues to this day, and may be witnessed in the large-scale inauguration ceremonies on opening night. In 2016, a crew of Kanaky breakdancers from Nouméa, in New Caledonia, took downtown Guåhan (Guam) by storm, performing high energy choreography that transformed their bodies into dramatic tableaux inspired by iconic Kanak architecture, and set to a soundtrack that mixed customary rhythms with rap, hip-hop and urban dance beats.

While the Festival has been a powerful tool for the promotion of Pacific arts internationally, it also, crucially, provides space for collaborative exchange. One of its greatest achievements has been to empower Pacific artists, providing them with a platform that centres indigenous knowledge and advocates for its primacy. Local histories and place are the focus of each Festival. At the most recent Festival in Guåhan (Guam), in 2016, a number of artists and collectives created works in situ, drawing on local and granular histories that have forged the physical, cultural and material landscape of the island. One such exchange was a large-scale mural project conceived by two Māori artists for the side of a building in downtown Hagåtña. Janine and Charles Williams, who have roots in New Zealand’s graffiti movement, travelled to Guåhan (Guam) as part of New Zealand’s delegation of over 80 artists. The mural featured their bold signature graphics integrated into a design of a large-scale portrait of the ko’ko’, or Guam Rail (Hypotaenidia owstoni), an endangered species of flightless bird endemic to the island.

The Williamses incorporate designs that celebrate the mana tapu (sacredness) of manu (birds) as a way of acknowledging their cultural importance for Māori and Pacific Islanders. The ko’ko’ is the national emblem for Guåhan (Guam), but has been extinct in the wild for nearly 40 years, decimated by the invasive brown tree snake introduced to the island. After a decades-long recovery effort, local conservancy groups have successfully reared the ko’ko’ and are reintroducing it into its natural habitat.23

On completion of the mural, New Zealand’s delegation of Māori and Pacific artists gathered with their indigenous hosts to unveil the work according to customary protocols.24 A live ko’ko’ attended the unveiling, the first time many locals had seen the bird first hand. The ceremony was led by tohunga (ritual expert) Te Kaihautu Maxwell, while Māori singer Maisey Rika performed a waiata (song).25 The CHamoru delegation sang ancient chants in response, their leader speaking of earlier times when their ancestors first arrived on the island during an era when the birds were plentiful. In a particularly moving moment, Kaihautu Maxwell honoured the bird with a hongi, a customary Māori greeting which involves bringing the face close so that the vital essence, or life force, encapsulated in the hau (breath) can be shared.

By focusing on local histories, the Williamses’ site-specific project supported the island’s indigenous community, drawing attention to some of the serious ecological issues facing the island. The act of coming together in ceremony creates unique opportunities that reinforce the kinship of Pacific peoples. This, in turn, helps raise the profile of indigenous issues and can hasten the trajectory towards self-determination and autonomy. Hosting nations attract significant media attention, an important asset for many indigenous communities whose historical legacies are dominated by settler colonial narratives and the threats posed by the climate crisis, militarism and globalisation. This was especially pertinent in 2016 for the host nation Guåhan (Guam), whose identity as a Pacific island is often eclipsed by the presence of the United States’ military and the powerful consumerism of Asian tourist markets.26

Quest for sovereignty

As a forum, the Festival not only promotes cultural revitalisation, but is a major rallying point for Pacific voices that strongly articulate regional calls for decolonisation and demilitarisation. Five decades after the first Festival in Fiji in 1972, the urgent challenges facing Pacific nations continue unabated. Corporations and extractive industries continue their excesses throughout the region, exacting large-scale devastation through mining, over-fishing and river pollution, all of which wreak havoc on the ocean environment and island habitats. The Festival allows a critical, and creative, space for indigenous voices to push back against these forces and to participate in their own strategies for resistance.

At the closing ceremony of the 2016 Festival, 12 CHamoru delegates unfurled red banners made from their official uniforms to broadcast the message ‘Decolonize Oceania, Free Guåhan’.27 Picked up by international media, the delegates’ protest drew attention to the ongoing legacy of colonial control. It also communicated solidarity with other indigenous Pacific communities fighting for independence and the right to self-governance. Dr Michael Lujan Bevacqua and Victoria-Lola Leon Guerrero, co-chairs of the Independence for Guam Task Force, explained the crucial importance of the Festival for them as CHamoru:

FestPac was an empowering space where we saw the vibrant and inter-connected sea of islands that we belong to in the faces, movements, creations and stories of the people who colonization has worked to separate us from. FestPac reminded us that we are a part of Oceania and that, like all people, we deserve to be free.28

They go on to explain that this heightened sense of solidarity with fellow Pacific peoples is crucial, because it means:

. . . we can see ourselves as more than the legacies that colonization has left us with. It means celebrating ourselves as more than just tourist destinations, nuclear testing sites, airports for transit, and bodies for exotic dances.29

The Festival continues to prove itself a powerful unifying tool in strengthening the collective identities of islanders by focusing on grassroots agency as a way to articulate political action and the empowerment of communities. Alongside the public, attendees include regional political leaders, diplomats and other government officials. In 2004, at the 9th Festival of Pacific Arts hosted by Palau, a delegation of 80 indigenous performers and artists from Taiwan attended the Festival for the first time. Their attendance was politically strategic in its acknowledgment of the deep cultural legacies that Taiwan shares with the island nations of Oceania to its east, and highlighted the shared Austronesian heritage of its indigenous peoples. An indigenous Taiwanese delegation has attended each of the subsequent Festivals.

As well as fostering unity, the Festival has also become a focal point for the growing Pacific diaspora in Australia, New Zealand, Europe and the United States. Its global reach allows the Festival to retain its edge and relevancy as a catalyst for strengthening the arts.

The future

Over the course of five decades, the Festival of Pacific Arts has flourished, consolidating unique aspects of cultural and artistic practice and creating precedents for practitioners to enter new spaces and venues. These opportunities have been revelatory. In a Pacific regime of value, the criteria for producing and evaluating art accommodates process (not a final end product) and the collective (not the single individual). The Festival’s investment in spiritual, linguistic and customary knowledge, and its long-term encouragement of mastery in these domains, have created a fertile landscape for artistic practice where art ‘by and for the people’ is taken seriously, and where there is no false dichotomy pitting ‘tradition’ against ‘modernity’. As Pohnpeian poet Emelihter Kihleng explains: ‘Everything is ancient knowledge’, and the Festival continues to vigorously present Pacific art and culture on its own terms, never looking for external validation.30

One outcome of pursuing this intrinsically Pacific framework is a resolute broadening of accepted categories for art. Touchstones for Pacific art include distinct parameters of value. In the Pacific, the set of standards by which quality and skill in art (just as the achievement of wealth or success in life) are guided responds to a longstanding lineage of knowledge enriched by reciprocal exchange, and longstanding alliances and relationships. Contemporary Pacific art turns away from the ‘disinterested’ aesthetic of modernity (where art is, or can be, appreciated in isolation) to a thoroughly engaged living dynamic. Art for Pacific practitioners is not removed from life and culture, or from transactions between people, but rather embraces them and is built from them. Pacific practitioners recognise that continuous negotiation is vital for the daily reconstitution and vibrancy of culture.

One of the region’s other pivotal forums, energetically showcasing contemporary Pacific art for the past three decades, is, of course, the Queensland Art Gallery I Gallery of Modern Art’s (QAGOMA) Asia Pacific Triennial (APT). Now in its tenth iteration, the Triennial presents new and site-specific works from the Asia Pacific region across two venues in Brisbane, Australia. QAGOMA’s unique commissioning process supports curators in the conception and planning of projects with Pacific artists and collectives that are developed over several years. These collaborations lead to some of the most innovative work in the Pacific region today — large-scale, ambitious projects that strategically extend customary practice into the ‘white cube’ gallery space. Many of the projects are cross-disciplinary, intergenerational and participatory. They focus on relationships and knowledge exchange, and the agency of the collective body as a vehicle to embody knowledge — features that drive home to audiences the living dynamic of Pacific cultures.31

Participants in the Jaki-ed weaving workshop for APT9, QAGOMA, 2018; from back left: Susanta Jieta, Rosie Elmorey, Clantine Moladrik, Roselee Jibon, Moje Kelen, Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, Susan Jieta, Terse Timothy and Mela Kattil, Aileen Sefiti, Motdrik Paul, Banithe Jesse, Artina Clarence, Helmera Fandino and Airine Keju / Photograph: Chewy Lin / Image courtesy: Photographer and University of the South Pacific Majuro Campus

Participants in the Jaki-ed weaving workshop for APT9, QAGOMA, 2018; from back left: Susanta Jieta, Rosie Elmorey, Clantine Moladrik, Roselee Jibon, Moje Kelen, Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, Susan Jieta, Terse Timothy and Mela Kattil, Aileen Sefiti, Motdrik Paul, Banithe Jesse, Artina Clarence, Helmera Fandino and Airine Keju / Photograph: Chewy Lin / Image courtesy: Photographer and University of the South Pacific Majuro CampusEncouraged to flourish in this new paradigm, Pacific artists have embraced this more inclusive approach, producing compelling art, which, according to Ruth McDougall, QAGOMA’s Curator of Pacific Art: ‘affirm[s] a sense of collective agency and authority’.32 No longer marginalised from the mainstream canon, the influence of these artists and their projects on international discourse and the contemporary art world is strong, nudging those in Euro–American capitals, who have always been its gatekeepers, to relinquish control. QAGOMA has been precise and deliberate in its execution of this bold agenda, which Director Chris Saines insists has been successful because it ‘meets artists where they are’.33

Like the Festival of Pacific Arts, the Asia Pacific Triennial is an event that supports the long-term development of relationships with Pacific artists on the ground, creating opportunities where previously these have been limited. For nearly 30 years, QAGOMA has been in the business of blurring boundaries to disrupt the expectations of non-Pacific audiences by dismantling art world distinctions between the centre and its alleged peripheries, and reframing the customary as contemporary. As Saines intimates, artists in APT ‘present their work in the context of being from here, rather than from elsewhere’ [author’s italics], a much-needed tonic that has changed the way Pacific artists are perceived the world over.34

As one of the longest-running celebrations of indigenous culture in the world, the Festival of Pacific Arts remains steadfast in its original mission to centre indigenous voices and elevate the creativity of Pacific peoples. The Festival, as well as the international art gatherings that have come in its wake, provide us with a critical lens for understanding contemporary art practice in the region today. More than simply a cultural space, the Festival is uniquely placed as an arena for political debate, enhancing visibility for Pacific Islanders and establishing a shared platform for solidarity, empowered by the energy and wealth of personal interactions. The thousands of islanders, artists and delegates who participate understand their role as twenty-first-century protectors of ancestral knowledge. They understand that their practice not only safeguards the past, but sets the course for a global future, which is guided by indigenous epistemologies that not only offer a pathway to future sovereignty, but powerfully declare continued resilience in the present.