Premier of Queensland, the Hon. Wayne Goss MLA, speaks at ‘The First Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT1) media preview, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1993 (seated behind, left to right: Max Bourke, General Manager, Australia Council; Richard Austin, OBE, Chairman of Trustees, QAG; Doug Hall, Director, QAG) / Photograph: Ray Fulton / Image courtesy: QAGOMA Research Library / © QAGOMA

Premier of Queensland, the Hon. Wayne Goss MLA, speaks at ‘The First Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT1) media preview, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1993 (seated behind, left to right: Max Bourke, General Manager, Australia Council; Richard Austin, OBE, Chairman of Trustees, QAG; Doug Hall, Director, QAG) / Photograph: Ray Fulton / Image courtesy: QAGOMA Research Library / © QAGOMA

Singapore’s eminent art historian, curator and critic Kanaga Sabapathy has spent four decades researching and writing on modern art of the region. Here Sabapathy recounts with Simon Elliott, Deputy Director, Collection and Exhibitions, QAGOMA, his early influential involvement in the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT).

Simon Elliott (SE): Take your mind back to the early 1990s when the Queensland Art Gallery (QAG) reached out to you with this idea of an Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art happening in Brisbane. That must have been a surprise? Tell me what went through your mind at the time.

Kanaga Sabapathy (KS): Surprise is absolutely spot-on. Not because this was coming out of Australia, but because it was coming out of Brisbane, Queensland! Rightly or wrongly, from where I was in Singapore, our view of Queensland was somewhat tainted by redneck conservatism. To be asked to consider to be part of what turned out to be an extremely large, extensive team of people cultivating interest in the complicated mix of regions that make up Asia and, of course, the Pacific (which remains relatively unknown to us in this part of South-East Asia) was mind-blowing, quite literally. And to plonk contemporary and modern art and artists in this mix was unimaginable at the time.

Having said that, my first encounter of Australia’s growing interest in the contemporary arts of the region happened first in Perth in 1987 with Australia and Regions Exchange/Artists Regional Exchange (ARX). While ARX was not a national endeavour, more a largely artist-run enterprise, having arrived in Perth, low and behold, there was this heavy mixture of people from South-East Asia in Australia.1

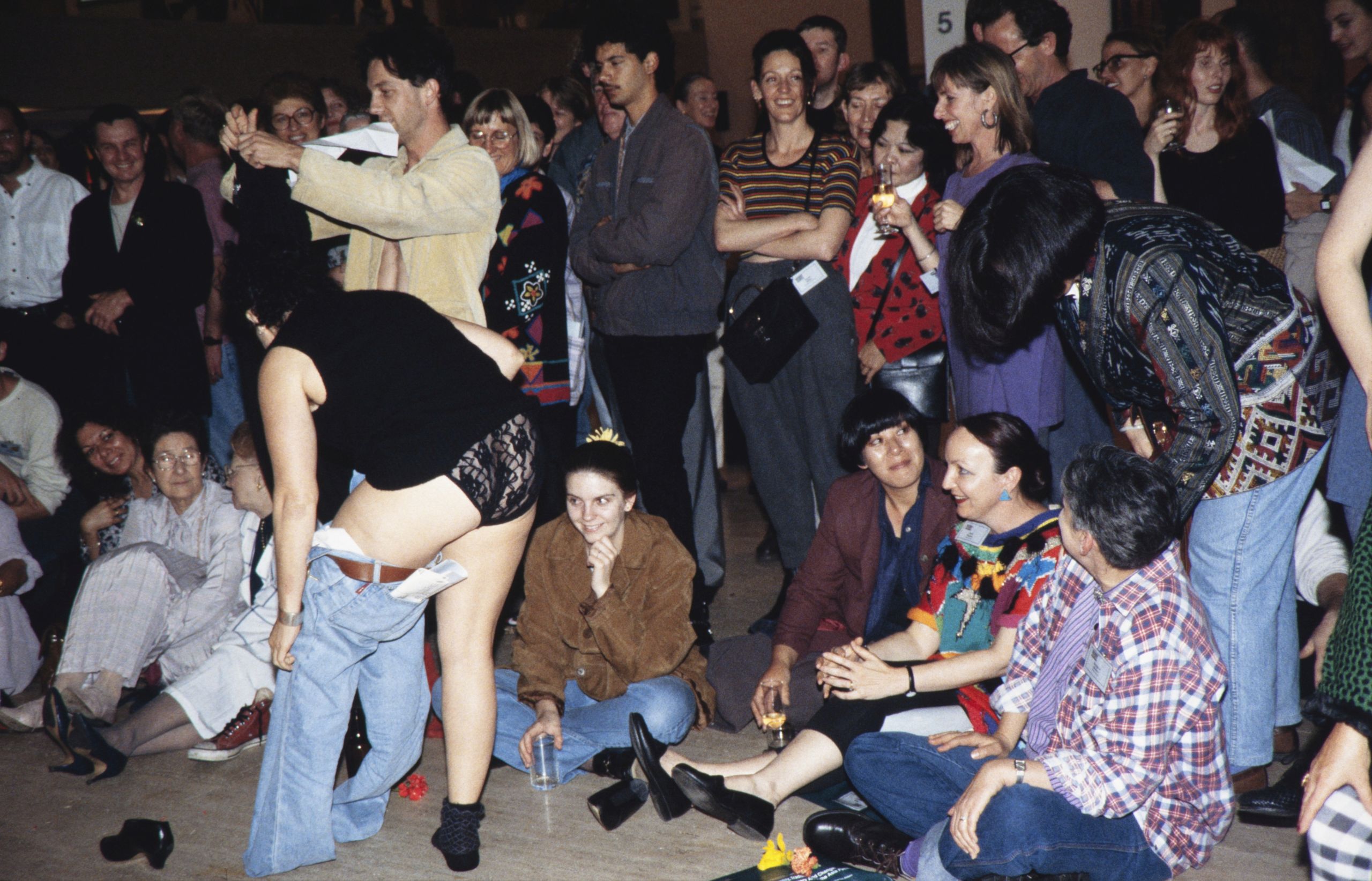

National and international artists, curators and academics participated in the APT1 Conference, Queensland Art Gallery 1993 (left to right): Dr Apinan Poshyananda, Bernice Murphy, Redza Piyadasa, Alison Broinowski, David Elliott and Marian Pastor-Roces / Photograph: Ray Fulton / Image courtesy: QAGOMA Research Library / © QAGOMA

National and international artists, curators and academics participated in the APT1 Conference, Queensland Art Gallery 1993 (left to right): Dr Apinan Poshyananda, Bernice Murphy, Redza Piyadasa, Alison Broinowski, David Elliott and Marian Pastor-Roces / Photograph: Ray Fulton / Image courtesy: QAGOMA Research Library / © QAGOMAIndonesian artists, such as Jim Supungkat, FX Harsono and Arahmaiani, were there, as well as Pinaree Sanpitak and critic Apinan Poshyananda from Thailand. We knew of each other but had never actually met until we assembled in sunny Perth. Alongside Australians Pat Hoffie and Julie Ewington, Alan Cruickshank and together with my colleagues above, we gradually gravitated towards the east coast and assembled in Brisbane for APT years later.

The second cluster of events that prepared us for our meeting with the QAG folks in 1992/93 was Fukuoka. In fact, Fukuoka Art Museum in Japan started very early in collecting, exhibiting and researching art of Asia and South-East Asia — both modern and contemporary. I remember their inaugural Asian art show in 1979, and they’ve had one every five years since, although their exhibitions have moved away from surveys to thematic and topically rooted exhibitions. Before leaving Fukuoka, the one individual who emerged from all of this carrying the torch and beacon for South-East Asia was Ushiroshoji Masahiro.2 I had dubbed him ‘Mr South-East Asia in Japan’, and I think more than anyone else he has doggedly, single-handedly and with great intensity developed South-East Asia as a field for museology, exhibitions and, I think, the beginnings of art-historical studies in Japan.

In 1992, there was an exhibition that came out jointly, as I recall, from Fukuoka and Japan Foundation named ‘New Art from South-East Asia’. They used the word ‘new’, ‘recent’ or ‘latest’, being not quite sure or confident that the term ‘contemporary’ would be suitable. So, they hedged around it — and I appreciate that, because when was the contemporary? We may ask historically, etymologically, when it began. So this exhibition gingerly declared itself as a kind of millennial projection, leaving the twentieth and heading into the twenty-first century. And it is at that moment, at that time, that things began to hot up in Singapore. In 1996 the Singapore Art Museum was established. The movements towards it began in 1990 with the establishment of several national and ministerial committees.

I remember some of them sort of envisaging Singapore as a renaissance city. To envisage Singapore as a global nodule or hub for culture and art and so on. These were the instrumental policy decisions being made in the ministries. And that led to the establishment of the Singapore Art Museum, which was mandated for collecting, exhibiting and producing knowledge on modern and contemporary South-East Asian art.

I should also acknowledge the celebrated conference convened by John Clark on Asian modernism and postmodernism at the Australian National University, Canberra, in 1991.

In the mix of all of this, there was one kind of flash-in-the-pan event that orchestrated and initiated by the Asian Art Society Gallery, New York, by Vishakha Desai. In 1992, she convened a two-and-a-half-day conference in New York and invited many of the people I have named to assemble there. And that is where we re-met one another. And it was Vishakha Desai’s initiative for Asia Society in that sense, corralling all of us in New York, which led to that phenomenal exhibition curated by Apinan Poshyananda, ‘Contemporary Art in Asia: Traditions/Tensions’ (1996). I think it was the first exposition held on such a scale in New York by a curator from Asia.

So these were the satellite events that were happening.

SE: That is quite a complex web of activities across the region and beyond that seemed to build towards what was to be called the APT. Who actually contacted you?

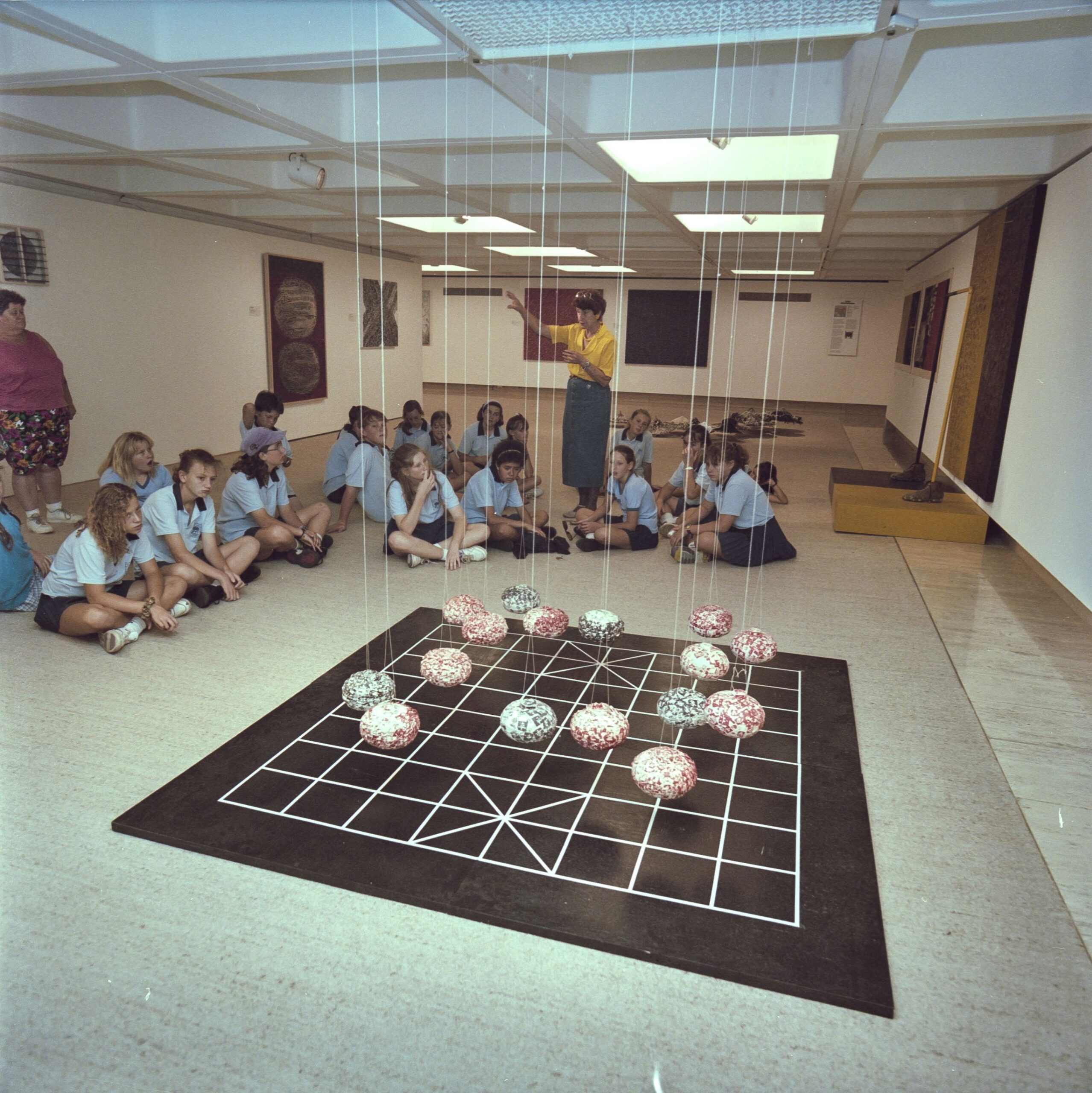

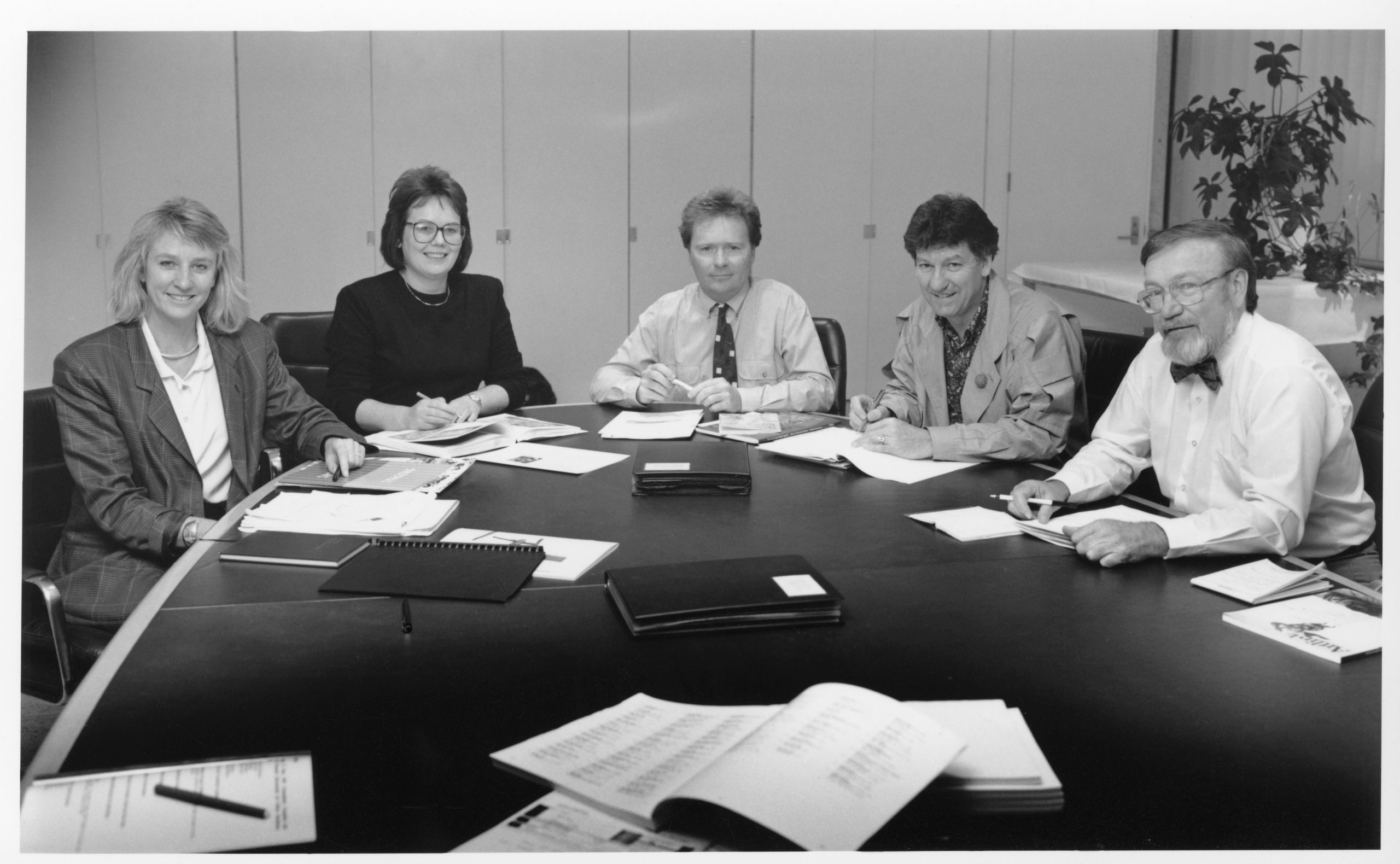

The inaugural AsiaPacific Triennial Consultative Committee (from left): Ms Alison Carroll, Visual Arts Consultant, Asialink; Dr Caroline Turner, Deputy Director and Manager, International Programs, QAG; Mr Doug Hall, Director, QAG; Mr David Williams, Head, Canberra School of Arts; and Mr Neil Manton, Director for South-East Asia and the Pacific, Cultural Relations Branch, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade / Image courtesy: QAGOMA Research Library / © QAGOMA

The inaugural AsiaPacific Triennial Consultative Committee (from left): Ms Alison Carroll, Visual Arts Consultant, Asialink; Dr Caroline Turner, Deputy Director and Manager, International Programs, QAG; Mr Doug Hall, Director, QAG; Mr David Williams, Head, Canberra School of Arts; and Mr Neil Manton, Director for South-East Asia and the Pacific, Cultural Relations Branch, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade / Image courtesy: QAGOMA Research Library / © QAGOMAKS: The person who tracked me down in Singapore was David Williams.3 He was with Alison Carroll, who was another important conduit looking after Asialink residencies for not only Asians and South-East Asians entering Australia, but also vice versa.4 David and Alison, as well as former diplomat Neil Manton, had worked in the region, especially Malaysia as strong supporters of local artists and were part of the advisory committee working with the [QAG Director] Doug Hall and [QAG Deputy-Director and Manager, International Programs] Caroline Turner to develop the APT.5 David travelled through Malaysia and possibly Indonesia and Thailand, and when in Singapore contacted me. I introduced him to Kwok Kian Chow who was the inaugural director of the Singapore Art Museum in 1996.

SE: You have set up the context and your surprise of being invited. When you got to Brisbane to see APT1, what did you see? What memories do you have of it?

KS: Simon, I fell in love with the Queensland Art Gallery. The QAG building, the layout — I felt this is what a gallery should be like. Of course, being beside the Brisbane River is a godsend. The building’s openness combined with the care and attention and scrupulous love for the works themselves; the way they were hung; where they were hung; and the manner in which one moved through the various levels. I thought the installation of works using the water mall at the bottom of the escalator going up to the first level was brilliant. That wonderful pool has always featured in APT, and the works selected to be put on that water feature were spot-on.

There were so many works I was struck by and am struck by even now. Montien Boonma’s Lotus sound 1992 with its serene bell sculpture; the hanging bamboo poles danced around by Dadang Christanto in reference to the missing souls of his homelands; shining steel by Shinro Ohtake; delicate and embroidered frozen fish by Lee Bul; strikingly direct paintings by Vasan Sitthiket; and Roberto Villanueva’s Ego’s Grave 1993 dug into the Gallery’s ground, with him in it. The exhibition was so touching, so moving, and I felt so connected with everyone assembled there. Never have I felt such a sense of communitarianism at an art event, for an art event, as I did then.

SE: And many of the exhibiting artists were present.

KS: Yes, that’s the other thing, because it wasn’t only the works, but also the artists who came with their works — they were invited to the inauguration, which I thought was wonderful. That doesn’t happen very frequently in these large congregations — group exhibitions where the artists are present and, of course, participate in forums devised for them to speak on their practices, quite distinct from the main conference papers and the conference platforms.

SE: There were many divergent views expressed at the first APT conference, as serious academics, artists and critics from around the region came together in one place, many I assume for the first time.

KS: Yes, there were many fruitful and sometimes intense points of view expressed, depending on where in the world the participants came from. I remember speakers such as Geeta Kapur from India crossing words with Mary Jane Jacob from the United States — not necessarily as an anti-American, or non-American — but pointing out that histories are not necessarily made and manufactured in Washington. Kapur’s observation was that there are wider histories and more authentic histories. And then [Malaysian artist and art historian] Redza Piyadasa gave a great insight into the relationship between artistic practice and philosophy. The terms ‘discursive’ and ‘discursivity’ were not quite known then, but I think this is what Piyadasa was aiming at. He gave one of the most eloquent representations of that view, I think, in the first APT.

ArtAsiaPacific — the magazine supplement to Art in Australia — was also launched in 1993 at APT1. ArtAsiaPacific grew to be such an important magazine for the region.6

SE: Two questions: how was the quality of the selection of works; and is it your opinion that the APT has never had an overarching curatorial theme?

KS: From my knowledge of South-East Asian art, I thought the quality of the work in APT1, 2 and 3 was variable. And I think this variability arose from the rather loose curatorial premise. I tended to look at what I saw as only extremely tentative moves. I think I approached the looseness of curatorial approach with both some trepidation and some excitement, but I’m afraid the trepidation prevailed. Having said that, I must also say there were works that were hypnotic and completely absorbing when approached individually rather than as relating to, conforming to, or nudging towards an overarching curatorial subject, topic, theme or issue.

The other point was that the broad-brush curatorial approach allowed great outcomes for those who participated in the APT. For many artists, being included was extraordinary for their careers. Sometimes it was the first time their work was seen outside their country, and often artists without strong in-country careers were lifted onto the international platform by the APT.

The other benefit of this loose approach was that there were some amazing, miniaturised projects, such as ‘Mapping the Mekong’ (APT6). I thought, why not insert something that doesn’t quite fit with the overall, amorphous gooey thing that was going on everywhere else; why not insert a particular, salient project to bring about a distinctive and microscopic view of a local concern or issue. Once there was a room devoted to North Korean pictures which came straight from leftfield. I thought, ‘What is going on here?’ Suddenly, North Korea. It looked terribly out of place, but wow!

So, I am still in two minds about whether one should be a little bit more directed curatorially and have a direction, or if one persists with a non-thematic, non-topical approach. It’s not a ‘free for all’ because certain standards, certain expectations are exercised by those who nominate works, and because of how the works are adjudicated and appraised internally within your institution for adequacy of display.

National and international artists, curators and academics participated in the APT1 Conference, Queensland Art Gallery 1993 (left to right): Dr Apinan Poshyananda, Bernice Murphy, Redza Piyadasa, Alison Broinowski, David Elliott and Marian Pastor-Roces / Photograph: Ray Fulton / Image courtesy: QAGOMA Research Library / © QAGOMA

National and international artists, curators and academics participated in the APT1 Conference, Queensland Art Gallery 1993 (left to right): Dr Apinan Poshyananda, Bernice Murphy, Redza Piyadasa, Alison Broinowski, David Elliott and Marian Pastor-Roces / Photograph: Ray Fulton / Image courtesy: QAGOMA Research Library / © QAGOMASE: So Kanaga, what is the impact of APT as you see it?

KS: That’s a bit difficult. Firstly, I think the APT was devised for Australia. It was Australia’s declaration, as a result of looking at the world in a different way geopolitically in the 1980s and 1990s — an effort to connect culturally and artistically with the rest of Asia. This is not to say that there were no connections, diplomatically, commercially and militarily between Australia and the rest of Asia prior to 1980s and 1990s. I think this was a deliberate policy coming out of the shift and the change, and we thought that it was really to satisfy those of us who talked about it: to satisfy an Australian mandate. This was Australia looking at the world and inviting the world to be present in Australia, rather than the other way around. Would such a geo-cultural scope — if I can use such a term — be feasible or tenable or desirable in Asia or South-East Asia? I doubt it very much. Not according to the way the ‘Asia Pacific’ has been formulated.

The Pacific, in this formulation, is considered to be on the eastern side of Australia; New Zealand and the numerous island nations that are in the Pacific. Those are somewhat remote from where we are in Asia, and I do not recall either within my work or in the work of my colleagues continuous and deep interest in art of those places being shown. I don’t think we have. So, it’s a particularly Australian focus. Did it have an impact for anyone else? I think for many artists it probably did. It came at a time of globalisation and internationalisation of art practices and the representation of these practices in various sites, in various hemispheres and domains. And in that sense, the APT provided a vast and almost limitless arena for exhibiting oneself and being seen.

And I think many of the artists who were shown at APT gained immensely in terms of confidence and advancing and developing their practices, their perceptions of who they are and what they are, both nationally and regionally, and then, at the third level, internationally. I think for many, APT was a vital platform to launch into the wider world. Many of them were already quite familiar with the region and being in the region, but beyond the region of South-East Asia — some things were going on in Korea and Japan — Australia really presented another dimension to many of these artists. And some of them have developed distinct and enduring practices in Australian communities since then.

There’s another aspect to your question, and that is the documentation of APT, which is my particular interest, of course. The publications that have been issued with the exhibitions are what one expects for any exhibition. But what I think is missing — now you have reached the tenth edition of APT — is an examination of the Triennial retrospectively as an exhibition, and as an exhibition that gives rise to discourse. A discourse that is not only particular to the exhibition but also exists beyond the realm of the APT. I think this is sorely missing, but then this is not only sorely missing from the APT, but also from many such organisations. Having produced ten editions, I think it is time for oneself and those who have been part of APT — as well as others who are looking on and developing their own exhibitions — to undertake critically registered overviews of what has gone on.

I say this because there is now emerging in the studies of art a particular momentum in looking at exhibitions as materials for critical and art-historical discourse. It’s new. It’s new everywhere. How do we study exhibitions? What do we do with exhibitions, having had them for X number of years, as in the case of the APT. What kind of epistemological frames do we bring to examining them? I think this is all so vital, not only for art history but also for exhibition-making itself.

SE: I’ll take that suggestion on notice. Let me ask my last question: has the APT run its course?

KS: Of course not. Ten editions are too few. You should have at least 30 before you even think of closing up shop. I’m not just talking numbers, but I think one has to be mindful of the duration required for an entity to develop, to grow and be cultivated. Before we say, ‘OK, we will set this aside for the next five years and perhaps revisit it afterwards’. There might be other ways of undertaking the Triennial — perhaps staging mini shows across the region with colleague institutions, or spread across the three-year span rather than having the one blockbuster every three years. Just a thought …

But I think it is important for Australia to not stop it right now. I think the APT is increasingly important, and I’m not just talking in terms of the present health situation. Now, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, the intensity with which nationalisms are gripping and crippling communities and nations is increasing. To me this is alarming. I fear that in less than ten years we seem to have abandoned so many ways of working, matters of relating, matters of talking, matters of communicating, wishing to or wanting to relate to each other.

I am not suggesting that art is a way out of it, but art is a constant reminder of the feasibility and the possibility of connecting and to remain connected. Because art brings to the surface innate, deeply held, profoundly lived modes of existence that are sufficiently common to many of us. I am talking about exhibits in the APT, and I think we have to try and resist this growing nationalism where possible. Exhibitions can occasionally provide moments to remind us to resist, and to celebrate the connectivity in humanity. We should hang on to that as long as possible and safeguard it.