Essay

Afterlives, aftershocks, afterthoughts: Suturing memories of loss and fissures in Nepal

Ashmina Ranjit / Nepal b.1966 / A Happening: Nepal’s Present Situation 2004 / Performance / Courtesy: Ashmina Ranjit

Ashmina Ranjit / Nepal b.1966 / A Happening: Nepal’s Present Situation 2004 / Performance / Courtesy: Ashmina RanjitReflecting on the past three decades of sociopolitical upheaval in Nepal, one must reckon with the unfathomable sense of loss and the fissures that have altered both the country’s political course and the everyday lives of its people. At the turn of the millennium, a ‘People’s War’, which was underway in the rural heartland, eventually brought down a centuries-old monarchy and challenged structures of caste, class and gender. Combined with decades of economic torpor, this war also led millions of Nepalis to leave their villages in search of better opportunities abroad. And, in 2015, a devastating earthquake ravaged the country’s infrastructure, pushing lives into further precarity. It is difficult to determine when the aftermath to such disruption begins, but the contemporary cultural landscape of critical and creative labour provides a space for collective dialogue to understand the implications of Nepal’s vicissitudes. Furthermore, it would be simplistic to treat the wounds of these circumstances as individual artefacts. Artistic and curatorial practices have thus focused on narratives that go beyond the scale of loss to reorient discussions on the interactions between the emotional and longitudinal forces that continue to shape our relationship with the recent past.

Remembrance as resistance

At the height of the decade-long conflict between the Maoists and the incumbent government, news of deaths, disappearances, massacres and riots was on the rise.1 On 1 May 2004, artist and activist Ashmina Ranjit staged A Happening: Nepal’s Present Situation to not only perturb Kathmandu’s apathy towards the armed conflict in rural areas, but also to subvert the national prohibition on public gatherings during a state of emergency. Ranjit, covered in black ink, walked alongside other performers in silence towards Singha Durbar, the seat of the Nepali government.2 It was a sombre procession of more than 100 black-clad individuals walking in pairs and taking turns falling to the ground, after which they would outline each other’s bodies with white chalk. This silent march was accompanied by a cacophony of wailing, broadcast simultaneously across dozens of radio stations. The juxtaposition of bodies moving in silence combined with eerie cries and lamentations activated the public space with an almost paradoxical sensibility of composure and chaos.3

The imbrication of politics, performance art and public space set the stage for a radical departure from the conventions of contemporary art in Nepal in the early 2000s. As an artist and activist, Ranjit’s work persistently presents the body as a medium through which accountability is sought from the state. Her play with the motif of time standing still as bodies fall to the ground contrasts stasis and crisis. The war becomes palpable through the collective falling and eventual disappearance of bodies that leave behind only imprints that are unaccounted for.

In 2006, the Maoists and the then government came to a peace agreement involving a ceasefire. What followed was a series of dialogues and negotiations on the nature of political transition. Some 14 years since the end of the civil war, the transitional justice process remains in limbo as survivors and family members of victims continue to demand truth and accountability from the perpetrators. Almost all cases remain uninvestigated or unprosecuted.4 In the context of complete state apathy, community-led memorialisation projects have become testimonies to the gross violations and atrocities committed by both the Maoists and the state.

‘Memory, Truth and Justice’ is a project that resulted from a collaboration involving a team of multimedia storytellers and activists who wanted to record personal stories of the People’s War. One such photo story, Nightmare 2018 recounts the experiences of Pasang Lama, who was detained and tortured by the government for being a member of the People’s Liberation Army.5 Lama frames parts of her own body in these images to recreate the visceral memories of torture. In doing so, she problematises the boundaries of memory and truth, as these photographs are unlike the journalistic images of war crimes and violence that often remain in the public memory. Nightmare reveals a central problem of the truth and reconciliation process: the truth of victims will always be refused until their memories are recognised as valid and as legitimate grounds for demanding justice.

Throughout the research process for the project, family members of the victims of the armed conflict would bring seemingly everyday objects with them: an analogue clock; a below-knee prosthetic leg with a well-worn shoe; an oft-thumbed New Testament Bible; faded items of clothing; and personal letters. Pooja Pant, one of the co-creators of ‘Memory, Truth and Justice’, points out that, in addition to embodying memories of the war, these objects also elucidate the truth that has been denied to the people — that their loved ones were tortured, disappeared and killed.

While commemorations can afford some solace over the ambiguous fate of loved ones, certain state-sponsored memorials have ignored the sacrifices of those lost to war.6 Activist and writer Indu Tharu lost both her father, Jokhan Ratgainyan, and her uncle, Jagat Chaudhary, in the war. They were killed by the Royal Nepalese Army for their affiliation with the Maoists. For several years, a wooden memorial gate dedicated to Tharu’s father and uncle, inscribed with both their names, stood at the entrance of Ranamuda village. Following Nepal’s local elections in 2017, a new concrete gate was erected, which did not display the names of Tharu’s relatives. An ambiguous Martyr’s Memorial Gate now stands at the village entrance with no mention of the identity of the martyrs.7 This current realpolitik of selective amnesia glosses over both the severity of trauma and the persistent impunity within Nepal’s political sphere. Remembering the lives lost remains an important act of resistance for justice that has yet to come.

Intimacy in estrangement

In 1996, as Nepal’s conflict dawned, Uttam Kumar Limbu left his family and job as a primary school teacher in Dhankuta to migrate to Qatar as a construction worker. In 2017, his son, Mekh Limbu, travelled to Qatar for a three-week workshop to document the lives of migrant workers, spending time in Doha’s labour camps. From this experience, Limbu developed Silent Portraits from Qatar and Kathmandu 2017, an intimate exposition of the intergenerational experience of diasporic estrangement mapped onto Nepal’s geopolitical transformations. In the work, he juxtaposes portraits of 19 Nepali migrant workers, each of whom has lived in Qatar between three months and more than 20 years, with satellite images of Kathmandu and a collage of footage capturing various ruptures in Nepal. Limbu explores silence and stillness in his work, letting faces and their unwavering gazes tell the stories of their toil and turmoil. These videos are played in a loop, each a palimpsest of more than two decades of fractures in personal and political relations.

There is a longstanding history of Nepalis migrating as traders, mercenaries and labourers. Since the end of the conflict in 2006, the sheer magnitude of people leaving to be wage labourers in the Middle East and South-East Asia has been unprecedented. Migrants provide much-needed remittances to fuel Nepal’s economic growth. Currently the billions of dollars sent back by Nepalese workers is commensurate with nearly a quarter of the nation’s gross domestic product.8 In Silent Portraits, Limbu interweaves the pervasive role of movement both inside and outside Nepal. Migrant workers and their experiences are intertwined with the global flow of remittances, internal migration within Nepal and the consequent transformation of the places they call home.

The same year that Mekh Limbu went to Qatar, musician Hemant Rana released ‘Saili’, a heart-wrenching ballad detailing the separation of a young Nepali couple in the face of migration. The song quickly became an anthem for the local realities of many Nepali families, going viral after its release on YouTube in 2017. Nepali popular music plays an integral part in making tangible the affective registers of diasporic longing, suffering and aspirations that serve to connect migrant workers to their homes. Songs of the ‘Lok Pop’ genre often use quintessential melodies rooted in Nepal’s central-western hills, combined with sentimental, nostalgic lyrics.9 The chorus to ‘Saili’ evokes tropes of love, loss and hope:

Suna Saili Saili diyoma telai hururu

Samjhi kahile narunu

Suna Saili Saili pardeshbata ma aaunla

Suna Saili Saili chalish katesi ramaula.Listen Saili, the oil in the lamp flutters

As you remember me, never cry

Listen Saili, I shall return from across the seas

And we shall enjoy our lives after our forties.

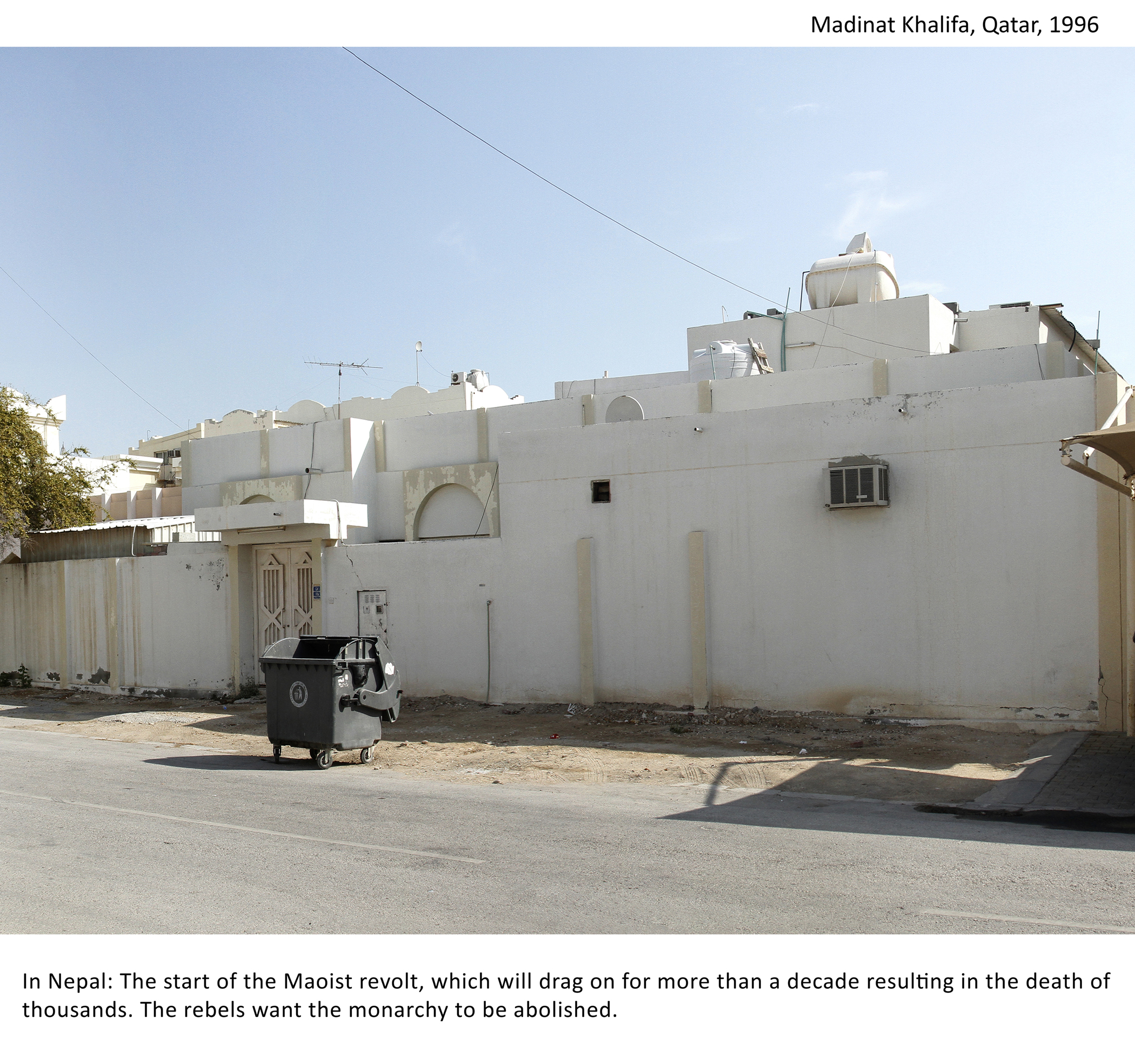

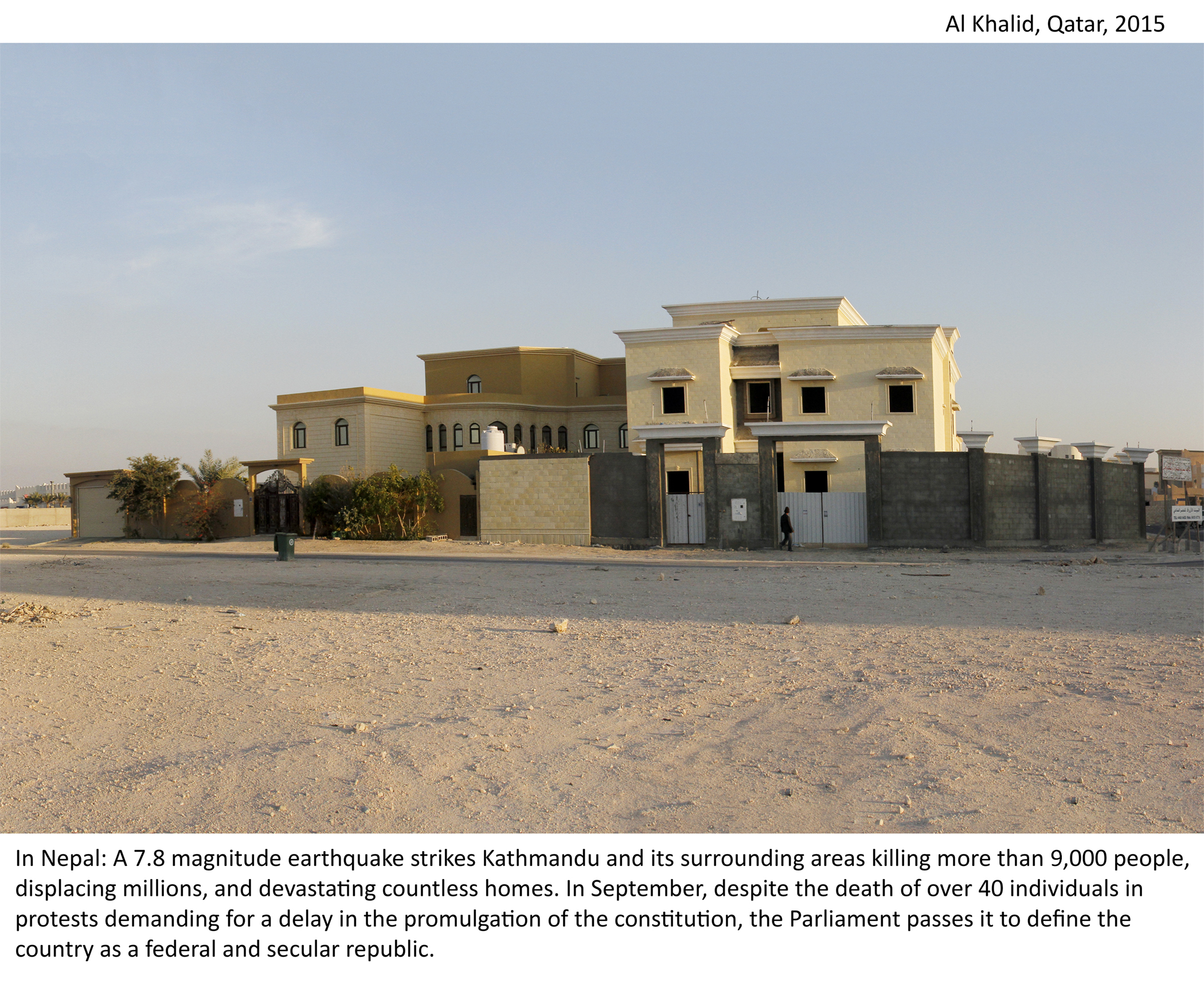

The emotional toll of migration rarely comes to the fore in Nepal’s day-to-day political discussions. Mekh Limbu, in his work Second home 2017– uses his father’s journey to trace the effects of personal separation and governmental apathy. He meticulously annotates photographs of buildings his father helped to construct in Qatar, with the date of construction and a parallel timeline of major events in Nepal. Contradictorily, these residences account for the rift created by migration within his own family. Through these images, Limbu creates literal landmarks of estrangement from his father. A house in Madinat Khalifa in Doha, completed in 1996, corresponds with the start of the conflict in Nepal and his father’s departure from his home country. Two distinct geopolitical temporalities are tethered, the micro-level experiences of a migrant labourer and the macro-level shifts in the country he left behind. In 2015, as Mekh Limbu’s father worked on a building in Doha’s Al Khalid, a devastating earthquake struck Nepal. As thousands of homes were destroyed in a matter of minutes, Nepalis continued to toil in distant lands. Uttam Kumar Limbu, nearing the age of 60, finally returned to Nepal in 2019, after spending 23 years constructing residential buildings in Qatar.

Shared spaces of healing

The immediate aftermath of the 7.3 magnitude earthquake that hit Nepal on 15 April 2015 resulted in an enormous loss of life, infrastructure and cultural heritage sites. In the ensuing aftershocks, Kathmandu-based artists and collectives responded to the devastation by mobilising efforts that directly addressed emotional and social trauma.10 Art historian Dina Bangdel noted:

Creativity in the arts became a powerful tool for healing, as artists moved outside their bounded spaces of the studio to create experiences and narratives that captured the pulse of the nation.11

Artist-led initiatives emphasised a grassroots approach that prioritised listening to and collaborating with community members to engage in a process of mutual healing.

Kailash Shrestha, co-founder of Artudio Center for Contemporary Visual Arts, is from Gairimudi, a village located in Dolakha district, which was the epicentre of the second major earthquake on 12 May 2015. During his visit to the village after the catastrophe, he organised a 22-day art camp, called Healing through Art, for the children in the community. Existing educational infrastructure, including school buildings, were destroyed, and the art camp therefore became a safe space for the children to engage in creative explorations.12 They were guided through a series of interactive and meditative activities, encouraged to pay attention to their environment, and given time to experiment with colour, gestures and organic materials. Some sessions were spontaneous, inviting children to interact with their surroundings and transform them into imaginative landscapes, which were used as an entry point to process traumatic experiences and emotions following the disaster.

The necessity for a shared physical site was also evident in the artist collective ArTree Nepal’s Camp Hub initiative in Thulo Byasi, Bhaktapur. The members of the collective worked with the Thulo Byasi community to facilitate temporary gathering spaces. In addition to losing loved ones and homes, residents had also lost traditional public spaces, such as falchas, which functioned as resting sites and meeting points for the elderly. These structures are not only physical spaces, they are also culturally embedded within Bhaktapur’s ritual activities. Using reclaimed materials, shelters made during Camp Hub were constructed with the help of volunteers. Such spaces provided a venue to gather, tell stories and alleviate pain.

During Camp Hub, Subas Tamang, one of the members of the collective, worked closely with community members to understand and document their experiences of the earthquake. Three months of research culminated in an interactive video installation Basibiyalo: A Sharing Space 2015, which was exhibited as a part of a larger exhibition, ‘12 Baisakh – Post Earthquake Community Art Project’, in Thulo Byasi. Tamang met individuals from varied walks of life: Ram Pyari Basukala, who lost her son, spoke of her experience at a hospital during the quake; Mangal Maya Suwal talked about her pregnancy; Harishankar Kuluju demonstrated his craft as a tabla maker. An interactive installment was then constructed in a repurposed falcha, the same site where three individuals had died during the earthquake — using this space held deep significance for the neighbourhood of Thulo Byasi. During the exhibition, audiences listened to the narratives of ten of their relatives and neighbours. Their stories were not only limited to loss but also addressed quotidian lives that continued despite the ordeal.13

Gathering narratives

Larger institutions in Nepal have often neglected systematic archival work to bring together narratives of the past, especially those that pertain to everyday individuals. Instead, such activities are often led by independent researchers, activists or artists. This disinvestment in intergenerational knowledge transfer and dialogues about history is a complex and layered issue stemming from Nepal’s tumultuous transitions that have fundamentally altered societal relations. Post-earthquake, community-led activism around heritage conservation sheds further light on the precarious condition of cultural memory, knowledge and oral history, which are all at risk of being permanently lost.14 Baakhan Nyane Waa, a youth-led, community-oriented storytelling event organised in public spaces, emerged from this need to forge intergenerational dialogue in order to document rich local histories and stories. Alina Tamrakar, one of the core team members, emphasises that oral traditions of storytelling around communal gatherings always existed, and their efforts aim to rejuvenate and preserve such intangible practices that are inherently intertwined with Kathmandu’s material heritage.

The phrase Baakhan Nyane Waa means ‘come, let’s listen to a story’, and each session typically begins with a short, guided tour of the locale where the story is based. A keen group of listeners follows the storyteller as they identify various sites, deities and information that will later feature in the narrative retelling. The procession of participants moves towards the final destination, usually a cultural site, where the storytelling begins as the audience settles down on woven straw mats and an oil lamp is lit. Staying close to the tradition of offering a local snack to the attendees during the storytelling, the audience is treated to popcorn at the end of the session. This performative ritual of collective sharing relies on heritage sites as cultural spaces to resist the forgetting of myths, ancestors and traditions.

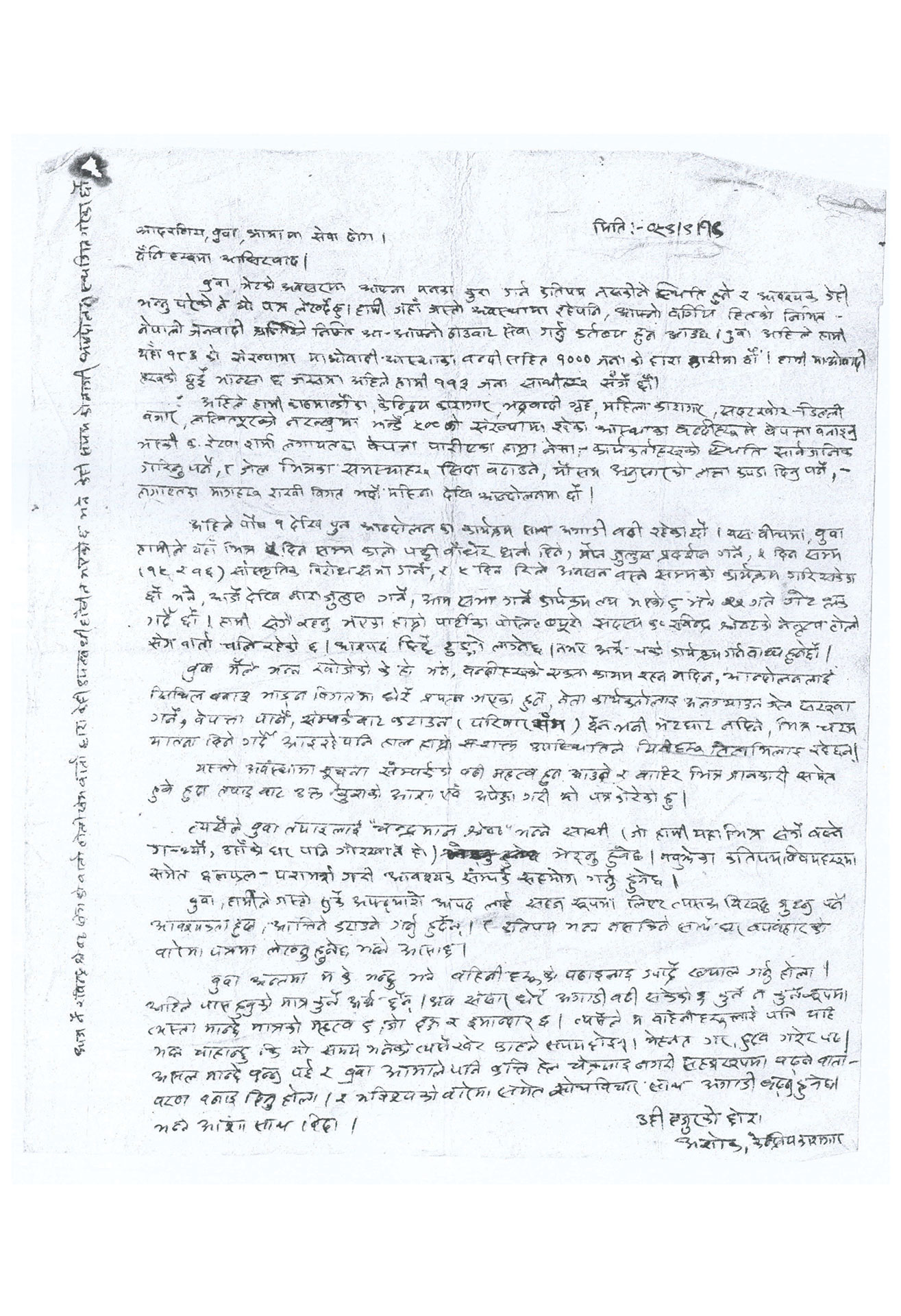

Along with oral literature, there have also been focused efforts to archive, preserve and present ephemeral documents. The collection of the ‘Memory, Truth and Justice’ project includes a letter written by Ashok Sunar (Akela), who was arrested on 22 November 2003 by the Royal Nepalese Army under suspicion of being a Maoist party member.15 The original letter, hidden in biscuit and noodle packets, was passed clandestinely to his family who would visit him in jail. The letter documents not only information about other inmates who were detained on similar charges, but also their efforts at organising and mobilising within the jail. The prisoners organised numerous days of sit-in protests, hunger strikes and general assemblies. The letter offers a glimpse into the everyday lives of those who were disappeared for being active political subjects of the movement. Through its very documentation and preservation, ephemera such as this letter resists its state of transience by acquiring an afterlife that contests the amnesia surrounding the war.

A closer look at similar archives concerning Maoist women in the collection of the Feminist Memory Project, collected by the Nepal Picture Library, reveals the often obscured, yet personal and deeply political, lives of women. In the Maoist movement and the People’s War, women’s participation and contributions are often viewed through a contradictory lens of liberation and victimisation.16 Some of the diary entries of these Maoist women reveal meticulously detailed recordings of female involvement — lists of names, dates, events and connections generate an alternative and feminist historiography of the movement. When these intimate annotations become part of the public archive, they hold the potential to rewrite ‘the relationship between visibility, history and memory’.17 Diwas KC, co-curator of the Feminist Memory Project, emphasises that the need to understand these memorialising efforts were constant, and the desire to remember the role of women in shaping the movement is abundant.

Ultimately, it is challenging to work with narratives that map a complex passage of time and space while constantly being connected and disrupted by conditions of precarity, whether it is war, violence, displacement or seismic fissures. In Nepal, the artistic and curatorial responses to these simultaneously personal — local and historical — global conditions are mediated through a collective and sustained dialogue with communities and their truths. The act of remembering requires a patchwork of artifacts, documents, objects and, most importantly, the voices of individuals — the same voices that are often discarded or dismissed from mainstream discourses. Primary sources, such as diary entries, handwritten correspondence, recorded testimony, or even storytelling sessions, can underscore a compelling history, even though they are often an afterthought in conventional studies of Nepal. In the laborious process of suturing together memories and material artefacts, one comes to understand the interconnectedness of the human condition to recover, process and make meaning from the spectre of the past in the present.